Potpourri

==> Joe Salerno offers a rebuttal to Paul Krugman’s high-five of “Lord Keynes” post about Mises on the Great Depression.

==> Two really interesting interviews from Tom Woods: Peter Schiff (where he talks about his dad, something I haven’t heard him discuss before) and Walter Williams (who near the end explains the connection between white people and his education, in a very funny way that would get Tom fired if he said the exact same thing).

==> Mises Canada launches a new academic journal.

==> A libertarian fiction contest. (And no that term is not a pleonasm!)

Krugman on Turkey

As faithful readers know, I was wondering how Krugman would deal with the fact that the Turkish central bank felt compelled to sharply raise its interest rates across the curve, in order to fend off an attack from the Visible Currency Vigilantes. (I am now clarifying that this is a more accurate description than “Bond Vigilantes” in the case of Turkey.) Well now we know:

“OK, did we need this? Turkey? Who was paying attention to Turkey?”

Yes, he’s being “funny,” but he really is admitting that the gurus didn’t see this coming, and that he himself needs to do more research before saying anything substantive.

However, lacking detailed information, Krugman is confident enough to offer this general reaction:

If you take secular stagnation seriously, as you should, then we have a chronic problem of too much saving chasing too few good investment opportunities, which means that you only feel prosperous when money thinks it has found more good places to go than it really has — and soon enough figures that out, with nasty effects.

So, it’s just as I said in my post: Austrians (and other small-government people) will say this just shows the dangerous game the world’s governments have been playing, while Krugman can blame it on too much saving.

The Bernanke Legacy

The WSJ recently ran an interesting assessment of Bernanke’s legacy, as he chairs his final FOMC meeting this week. It opens with this provocative paragraph:

As the Federal Reserve Chairman prepared to step down, the encomiums rolled in. “The most successful tenure in Fed history,” said the S&P economist. Added a former Fed Governor: “He has been called, and I think justifiably so, the greatest central banker in history.” He was the man who saved the world, a genius, the maestro.

The trick here–as perhaps the term “maestro” gave away–is that these accolades accrued to Alan Greenspan upon his descent from power. When he handed over the keys to the printing press in 2006, it was not yet obvious to everyone just how much damage Greenspan’s easy-money policies had baked into the cake.

The WSJ piece points out something I hadn’t realized: “As Fed transcripts show, Mr. Bernanke was the board’s intellectual leader in its decision to cut the fed-funds rate to 1% in June 2003 and keep it there for a year.” Elsewhere I have made the case that this extraordinarily low interest rate policy helped fuel the housing bubble, but I never knew Bernanke had been instrumental in pushing it through.

Time will tell–perhaps sooner than many of us realize–just how much mischief Bernanke has, in turn, bequeathed to his own successor. But when reflecting back on his legacy, let us not forget the following string of systematic failures to understand just how bad things were unraveling before the crisis struck in 2008:

The Kronies

I had seen this floating around, but never thought it would be worth my time to click. But a buddy emailed it to me directly, and yep, it’s pretty funny.

Regression Pitfalls: Why Growth Rate versus Level Could Be Crucial

Daniel Kuehn and I have been reading a lot of the major papers in the minimum wage debate. (I had asked Daniel if he would be willing to work through these papers with me, since this is his area and [given our different political perspectives] I wanted to make sure I was being fair to the guys arguing the case for raising the minimum wage.) Some of Daniel’s very helpful posts are here, here, here, and here.

I am going to be writing more on the broader debate in other outlets, but for the present post I want to spell out a crucial point that Meer and West raise in their 2013 working paper. Specifically, if the minimum wage doesn’t cause a sharp reduction in the level of employment, but instead permanently reduces the growth of employment, then a regression looking for a level effect might seriously understate the minimum wage’s influence.

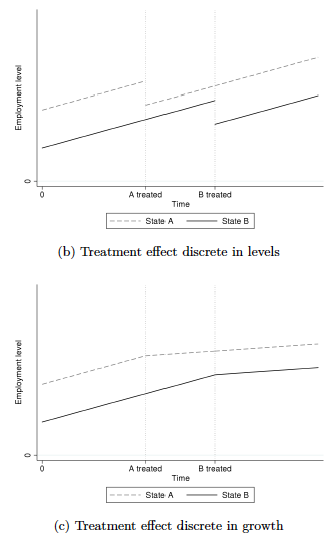

In this post, let’s not worry about the context of the minimum wage, but instead focus just on the narrow econometric point, because at first glance it’s counterintuitive. So, consider the following two scenarios (taken from Appendix A in Meer & West):

The idea is that some “treatment” is applied to State A first, then after some time has passed the same treatment is applied to State B. (Here “state” means an actual territorial unit, i.e. one of the 50 states of the Union.) The time durations are chosen so that the pre-treatment period is exactly the same length as the post-treatment.

As the charts clearly illustrate, in case (b) the treatment causes a one-shot (but permanent) reduction in the level of the variable of interest, while in case (c) the treatment causes a permanent reduction in the growth of the variable of interest.

Now, if we run a “differences in differences” (DiD) regression and choose the level of the y-variable as our dependent variable, then in case (b) it will attribute a negative coefficient to the treatment variable, while in case (c) the regression output will report no effect of the treatment. In contrast, if we run a DiD regression and analyze the growth of the y-variable, then in case (b) it will show no effect of the treatment, while in case (c) it will correctly assign a negative coefficient to the treatment variable.

Thus, if you accept these claims for the sake of argument, you can see the relevance to the minimum wage debate: If raising the minimum wage primarily affects the growth of employment, then the typical regressions in the literature (which look at the impact on the level of employment) could be vastly understating the actual effect.

To repeat, at first this seems counterintuitive. After all, we can quite clearly see that the treatment in case (c) has made the level of employment lower than it otherwise would have been; why wouldn’t a regression looking at level effects pick this up?

One way to see it is to read the discussion in Meer and West’s appendix. It has to do with the fact that the DiD estimator uses an “indicator variable” that is the same for both states except in the middle time interval. This makes the common “time trend” variable soak up the actual work that the treatment is doing. (Obviously I’m putting this into my own words.)

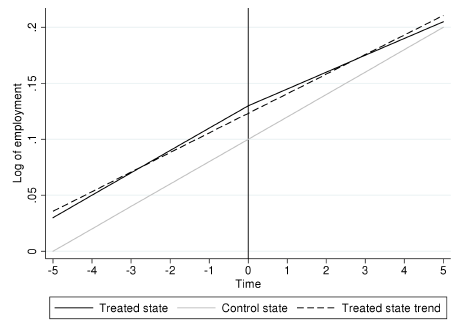

I think the way to make this “click” intuitively is to look at a different graph, this one from Meer and West’s Appendix B:

Now in the chart above, the “control state” (for which there is no treatment) chugs along at the same rate of growth the whole time. (That’s why the logarithm of its level of employment is a straight line.)

In contrast, employment in the treated state was originally growing at the same rate (though it had a higher level, initially), but then after the treatment it suffered a permanent reduction in the rate of growth. (Be sure you are focusing on the solid line, not the dotted one.)

Now, the dotted line shows the trend of employment in the treated state, over the entire period. Before the treatment, the treated state grows “above trend,” while after treatment, it grows “below trend.” (Note that if we were to plot the control state’s time trend, it would overlap perfectly with the actual employment level; for any interval in this graph, the control state employment would be growing “exactly even with trend.”)

So Meer and West are here illustrating a huge potential pitfall in including “state time trends” as a control factor in these types of analyses. In the above example, a regression on the level of employment, with a state time trend included as a variable, would show no effect of treatment. Daniel made this “click” for me by pointing out that if you shift the dotted line in the diagram down just a tad, so that it lines up perfectly with the solid line, then it’s “obvious” that the treatment had no effect on the level of employment in the state: The dotted line and solid line end up at the same level, at the last time period.

UPDATE: In the comments, Daniel elaborates on what happens in the regression that corresponds to shifting the dotted line in that way: “the intercept is accounted for by the fixed effects (geographic fixed effects effectively give every geographic area their own intercept). So if you clean out all the differences in the intercept, you see what controlling for the trend does.” Also, to be clear, Daniel is not agreeing that the “revisionist” studies are wrong; he is just clarifying what Meer and West are claiming, and how their cute pictures relate to the econometric specifications in the minimum wage literature.

Now to be sure, these hypothetical examples don’t prove that the empirical studies finding little impact of the minimum wage are necessarily spurious. However, they do highlight the serious pitfalls in such undertakings, and in particular we can see how including geographical “trend” controls might end up obscuring the quite real impact of the policy.

Peter Schiff on The Daily Show

On Facebook, I see libertarians are blasting Schiff for walking into an obvious trap. Give me a break, kids: If Samantha Bee wants to interview me tomorrow about private defense agencies, I’m saying “yes.” You don’t turn down the Daily Show.

The Daily Show

Get More: Daily Show Full Episodes,The Daily Show on Facebook

Is Turkey Benefiting From an Attack of the (Visible) Bond Vigilantes?

In addition to claiming that the bond vigilants are invisible (i.e. nonexistent), Paul Krugman has also argued that even if investors around the world suddenly lost confidence in Treasury bonds (because of fears over Uncle Sam’s profligacy), it would actually be good for the economy. For Krugman’s argument to apply, a country needs to (a) have excess capacity, (b) have its own currency, and (c) have debts largely denominated in that currency. These conditions apply to the US and Japan, which is why Krugman quite clearly said that these two economies would benefit if investors suddenly lost confidence in their bonds.

In this context, what are we to say of the situation in Turkey, where the central bank just jacked up interest rates quite sharply to stem the depreciation of its currency? Well, it issues its own currency (the Turkish lira), and its unemployment rate hit 9.9% in December 2013, slightly higher than the annual average rate (according to IMF) of 9.8% in 2011. (It had fallen in 2012.) Meanwhile, just eyeballing the chart from this forex website, the lira fell against the USD by easily 10 percent over that period (it depends when you start), not counting the rapid plunge this month.

Does the Turkish government / central bank have a lot of foreign-denominated liabilities? I have no idea. But at the very least, it looks like we now have to add Turkey to the list of countries (such as Greece) where Krugman et al. will need to explain why, “It can’t happen here.”

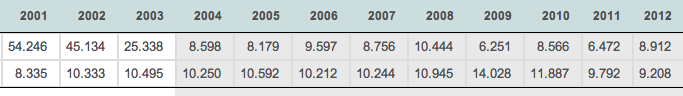

In case anyone is curious, here is a screenshot of Turkish consumer price inflation rates and unemployment rates, from 2001 to 2012, from the IMF:

What does the above data mean? Who knows? I can definitely tell you an Austrian story where the above data are just what we’d expect to see, and Krugman can definitely tell you a Keynesian story that does the same thing.

Recent Comments