LSE Climate Economics “Expert”: Liar or Stupid?

I report, you decide.

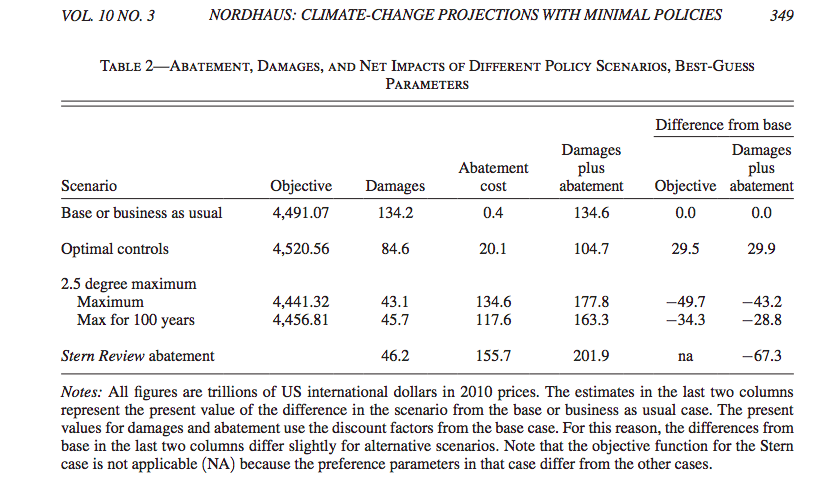

I am working on a study for the Fraser Institute that relies on the work of William Nordhaus. Long-time readers of my stuff know the irony of this work, because Nordhaus won the Nobel (Memorial) Prize in 2018 for his pioneering work on climate economics, on the same weekend that the UN released its Special Report on limiting global warming to 1.5C. The irony comes from the fact that Nordhaus’ own work shows that even a 2.5C limit–let alone a 1.5C one–would be so economically damaging, that it would be better if governments did nothing at all about climate change.

So in response to a reviewer report on my study draft, I went digging around for more recent commentary on Nordhaus. I came across the following in an essay from Bob Ward, Policy and Communications Director, at the London School of Economics’ Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment:

Professor Nordhaus stressed during his [Nobel acceptance] lecture that climate change is a very serious problem and that a universal carbon price should be introduced to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Nevertheless, Professor Nordhaus’s latest results have been seized upon by climate change deniers and so-called ‘lukewarmers’, who deny the risks of climate change. For instance, Dr Bjorn Lomborg, who has a track record of misrepresenting the results of climate research, recently wrote in another inaccurate and misleading article for ‘Project Syndicate’ that Professor Nordhaus’s showed “aiming to reduce temperatures more drastically, to within 2.5°C of preindustrial levels, would drive the cost beyond $130 trillion, leaving us $50 trillion worse off”.

In fact, the journal paper by Professor Nordhaus to which Dr Lomborg claims to have been referring shows clearly that unabated climate change would lead to damages of US$134.2 trillion (discounted present value, 2010 prices) as a result of global warming that would exceed 4°C by the end of the century. By contrast, limiting global warming to 2.5°C would cost US$134.6 trillion, but would still lead to damages of US$43.1 trillion.

Now what is hilarious is that (a) if you go to the Nordhaus paper that Ward links to, you will see Bjorn Lomborg’s summary is correct (looking at the “Objective [function]” column, or the dollar figure is $43.2 trillion if you look that way), and (b) once you know the scoop, you can re-read Ward’s own summary and see that it doesn’t contradict what Lomborg said. (!) I’ve attached the relevant table below for your convenience.

So my question: Did Bob Ward just not know how to read Nordhaus’ table, and confidently call Lomborg a denier, and his article inaccurate and misleading, out of ignorance? Or did Ward know that Lomborg had correctly summarized Nordhaus’ table, and was just hoping most readers wouldn’t bother to check or know how to?

Is it possible that Shaw is neither lying not stupid but just practicing the Krugman-inspired art of misdirection? Which specific sentence in the bit you quote is inaccurate rather than merely misleading ?

BTW: I used to be worried by global warming but now realize that even the worse case scenario of US$134.2 trillion of,losses can easily be fixed by a stroke of our new President’s pen.

Ward not Shaw.

Misdirection *is* lying

If we take stupid as a given, then we just need to solve for whether or not he is a liar.

Ummm… if the governments actually did do “nothing at all” a lot of oil production might end or at least slow way down… in many countries, the oil companies are effectively the government, in so far as they seem to have more control over the militaries than the actual elected officials…

This was published in 2005… obviously what was recent in 2005 isn’t all that recent now, but anyway…

So, oil production in parts of the world, including Ecuador, is enabled by military violence and theft of land.

And you see that in the United States too, or at least the “theft of land” part, with “split estates”, where the government decided it owned the mineral rights a long time ago, not the indigenous people nor the homesteaders, and somehow the mineral rights end up legally owned by oil and gas companies. In many western states, mineral rights are considered dominant over surface rights, functioning as eminent domain for oil and gas companies. The result is that oil and gas companies are allowed to steal land from farmers and other people. A similar legal tool used in some other states is forced pooling, where if a certain percentage of landowners agree to sell, then the rest are forced to sell, whether they want to or not.

So if “the government” did “nothing at all”, the oil and gas economy would come crashing down.

Sorry, I forgot to include the link for that. Here it is:

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2005-06-18/ecuador-oil-companies-links-military-revealed/#

“Ummm… if the governments actually did do “nothing at all” a lot of oil production might end or at least slow way down… in many countries, the oil companies are effectively the government, in so far as they seem to have more control over the militaries than the actual elected officials…”

Openly committed rights-violator-countries (like the Arabs) with nationalized oil industries have failed to accomplish what you’re talking about.

The violations you’re talking about will decrease with an increase in free markets.

Time to Lay the 1973 Oil Embargo to Rest

[www]https://www.cato.org/commentary/time-lay-1973-oil-embargo-rest

“… most Petroleum Exporting members likewise declared that they would stop selling oil to the United States until America abandoned support for the state of Israel. The fallout from those events so traumatized the nation that, 30 years later, the ’73 crisis still haunts both foreign and domestic policy makers. …”

“… Let’s start with the embargo. Most people believe that it was directly responsible for long gasoline lines and for service stations running dry. The shortages were, in fact, a byproduct of price controls imposed by President Nixon in August 1971, which prevented oil companies from passing on the full cost of imported crude oil to consumers at the pump …”

“… By May of 1973 (five months before the embargo), 1,000 service stations had shut down for lack of fuel and many others had substantially curtailed operations. By June, companies in many parts of the country began limiting the amount of gasoline motorists could purchase per stop. …”

“… Did the subsequent embargo stoke the crisis further? No — it was an economically meaningless gesture. That’s because the embargo had no effect on imports. Once oil is in a tanker, neither Petroleum Exporting Countries nor OPEC nor Knick‐Knack‐Paddywack can control where it goes. …”

“… Saudi oil minister Sheik Yamani conceded afterwards that the 1973 embargo “did not imply that we could reduce imports to the United States … the world is really just one market. So the embargo was more symbolic than anything else.” It took a while, however, for Americans to figure this out. In his memoirs, then Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote that, looking back, “the structure of the oil market was so little understood that the embargo became the principle focus of concern. Lifting it turned almost into an obsession for the next five months. In fact, the Arab embargo was a symbolic gesture of limited practical importance.” …”

“… Moreover, the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ threat to gradually cut oil production to zero until Israel left the occupied territories lasted all of a month and a half. On Dec. 4, 1973, the Saudis cancelled their promised monthly 5 percent cutback and the rest of the Petroleum Exporting Countries followed. In January 1974, they ordered a 10 percent production increase. No more was heard of the threat. …”

“… First, oil embargoes are symbolic gestures and not worth worrying about. Second, oil producers will not sacrifice revenue to make political statements. Third, policymakers are economically illiterate and prone to hysteria.

“In short, the oil weapon is a myth. It’s high time that we stop believing in ghosts.“

I’m a little confused what oil embargoes have to do with land theft and murders… I mean, I’m sure there’s a link, but is the oil embargo supposed to make land theft and murders better or worse?

Unfortunately, many of them also seem to be unwilling to sacrifice revenue to respect basic morality, like honoring the local stewards of the land and refraining from murdering them and/or stealing their land and/or polluting their land.

What I mean about the governments doing “nothing at all” was, among other things, refraining from providing military and/or legal assistance to land theft and other crimes used in oil production.

Actually doing things with some minimal moral standards, e.g. consent of the local landstewards and refraining from reckless pollution, would slow things down, and some landstewards might decline to offer consent at all, stopping production in those areas.

“in many countries, the oil companies are effectively the government”

Other way around, actually. In many countries, the government is effectively the oil company, ie the monopoly oil producer is a state own corporation. Saudi Aramco only recently became a publicly traded company in 2019 and the Saudi government still own the vast majority of shares. China National Petroleum Corporation is a state-owned enterprise. Gazprom, Russia’s second largest oil company, is majority state-owned. National Iranian Oil Company is government owned. Petrobras in Brazil is state-owned. Pemex in Mexico is state-owned. Equinor in Norway, state-owned. Kuwait Petroleum Corporation, state-owned. Eni in Italy is about 30% state-owned, with a controlling vote in certain circumstances. PTT in Thailand, state-owned. SOCAR in Azerbaijan, state-owned. IndianOil. Indonesia’s Pertamina. Bharat Petroleum, also India. Sonatrach in Algeria. Hindustan Petroleum is majority state-owned. Malaysia’s Petronas. PDVSA in Venezuela. All state-owned and/or operated. And those are just the ones among the largest oil companies in the world.

In order for governments of the world to “do nothing” in the oil and gas industry, they’ll need to do quite a bit of privatization.

I mean, is there really much difference between:

(in many countries) oil companies = government

and

(in many countries) government = oil company

???

Whether the oil company takes control of the government, or the government takes control of the oil company it’s the same basic idea: people use power to profit and profit to gain power, especially if they lack basic morality. (In the case of Ecuador, the example I gave, it seems to be the oil companies taking control of the military branch of the government.)

“Privatize”? What is “privatize”? I read about private armies, such as Pompey’s private army. Pompey is known for saying, “Do not quote laws at men with swords,” while leading his private army around. And I also read about people wanting to privatize the military, which seems rather unlikely to accomplish much given Pompey’s example (and other brutal generals who lead private armies). With all this talk of private armies and privatization of armies, I guess abusive militaries are not considered the defining feature of government, which is odd because they do seem to define who’s in power.

I think demilitarizing the oil companies (and the governments, for that matter) would be more to the point, although since they are likely to resist being demilitarized, that’s more a vague goal than any kind of strategy.

The difference is that despite you saying that there are “many countries” where the former situation exists, as far as I can tell, there are actually none.

The link I provided:

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2005-06-18/ecuador-oil-companies-links-military-revealed/#

lists four examples:

* Ecuador

* Burma

* Nigeria

* Columbia

The common thread seems to be a lack of democratic control over the countries’ armed forces, making it easy for the oil companies to buy them out. So this likely also occurs in other countries with weak democratic controls over the militaries.

This is the classic stationary bandit vs roving bandit model … and the roving bandit is inevitably worse. Once that bandit has the opportunity to raid resources and then move on to raid elsewhere, that process is incredibly efficient for the bandit. There is no need to maintain capital, and the resources raided can be obtained at extremely low cost to the bandit.

Laws are only beneficial amongst people who have an interest in long term productivity … which is why the stationary bandit is much better. This guy is forced to consider the trade-off between resources raided today and what will be available next year and the year after. Even the worst corruptocrats like Pelosi and Biden are confronted with the reality that they and their families must live in the world that they create for themselves.

I think you are mostly right. Although some stationary bandits may be too insane to realize just how much damage they are doing. Mao comes to mind. Horrible person, but possibly insane enough to not realize just how horrible he was.

We might also note that a bandit who rules from afar, like King Leopold II over the Congo, has far less to fear from the people he oppresses than one who rules from nearby, like Mobutu over the Congo.

Leopold got some pushback from his own people, and from Europe in general. He was very unpopular even in his lifetime and modern Belgians are kind of sheepish and embarrassed about their previous king. You probably figure he deserved worse … and if he lived in Africa he very likely would have got more serious payback.

I agree in principle though, rulers far away tend to be worse, or at least have the potential to be a lot worse. Ögedei Khan was inclined to order the massacre of people he never met in places he never visited … but he kept his empire expanding, treasure and captives rolled in, so he was considered successful by his own people.

Deserve? I do not know what King Leopold II “deserved”. What does a person “deserve” for killing and torturing (by means of command responsibility) millions of people? Trying to think about this breaks my head, like trying to divide by 0. Perhaps a better question is, what did the Congolese deserve? Certainly better than to have to live and die in fear of King Leopold II and his agents.

Sure, Leopold II got some pushback from Europeans, most notably from Edmund Dene Morel and his Congo Reform Association. But he also had many people cooperate with him — a king cannot kill millions of people who live on a continent probably never even visited without others to do his bidding.

King Leopold Ii is noted for being a brazen liar. Although he enslaved millions of Africans, he claimed to be freeing them from Arab slave traders and not profiting at all. (The Arab slave traders were real, but my understanding is that King Leopold Ii fought them as one might fight a competitor, as he clearly had no objection to enslaving Africans.)

I have heard/read that there are still some in Belgium who deny King Leopold II’s brutality… I do not know how common this is, but I imagine it is similar to how there are Holocaust deniers who live in Germany and people who deny the USA’s genocidal history against American Indians who live in the USA. And a lot of Turks still deny that the Armenian genocide was in fact a genocide. Always, in every country, there seem to be some people whose idea of patriotism involves denying the worse crimes committed by their countrymen of the past (or present).

See for example:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53017188

It is a strange thing that environmentalist groups will inevitably propose central planned solutions, and demand that governments override the rights of property owners, imposing complex, confusing and often unhelpful regulations … when everywhere central planning has been attempted, the environmental outcomes have been awful.

If the same environmentalists actually did the reverse, and demanded stronger protection for individual property owners (e.g. family farms, tribal lands, etc) then mining companies would need to pay a higher price (i.e. a market price) for what they use, and would therefore be more careful with those resources. This in turn would extend all the way up the value chain. People would become less wasteful because the price they pay reflects the cost of what they use.

That said, the pragmatic reality is that governments run a protection racket … whoever pays the highest price gets the best protection. Subsistence farmers, or small-scale market farmers are not in a good position to buy top-dollar protection while the oil companies make sufficient profits to cover the expense of hired muscle … regardless of whether that be private security companies or government pay offs or a bit of both. There’s a bit of a gap between Libertarian theory which presumes everyone always plays nice and eschews the use of violence to obtain economic ends … vs what actually happens which is that violence is a commodity that gets bought and sold.

If governments did nothing at all they would no longer be governments but the basic calculus of hiring someone to defend your property would be no different. Some other group would simply run the same protection racket and one again sell to the highest bidder like any business.

You think this because you listen more to wealthy, politically influential environmentalists than to grassroots environmentalists around the world, including places like Brazil and the Congo.

Wealthy, politically influential environmentalists tend to be out of touch with what less wealthy, less powerful people have to deal with. (The same could be said of wealthy, politically influential people of most types.)

For example, it turns out that if forced labor was a country, it would be the third largest contributors to climate change, after China and the United States.

So abolishing forced labor would go a long way towards saving the planet.

You can read about this in “Blood and Earth” by Kevin Bales.

But a lot of wealthy, politically influential Americans are unaware of this. (Please note that I use the term “wealthy” in the global sense, and a huge proportion of the world’s top 1% richest people reside in America and other first world countries, and often don’t know they are in the top 1% and believe they are poor.)

Take Greta Thunberg … if she got a real job, and I never had to listen to her again that would be great, but unfortunately she is everywhere, the media love her. Someone discovered that Adarsh Prathap was the author of her supposed Facebook posts … I don’t read Facebook but apparently there was some way of figuring that out. Turns our Prathap is part of some UN Climate Change group … anyway, despite the lack of authenticity, faith in Greta remains unshakable. Some day she will save us from something. There’s your face of environmentalism right there.

Living in a fairly wealthy country, I’m confronted with what I see around me, which tends to be a mix of middle aged wealthy, politically influential environmentalists (mostly connected to some government program) plus younger, and not so wealthy activist kids who aspire to be politically influential (and aspire to be wealthy too but don’t talk about that). It’s very easy to get government benefits in Australia, meaning that someone can be a professional activist while being supported by the taxpayer, even when they are starting out with no skills.

Not sure if it makes sense for forced labor to be a country. Personally I will worry more about “Climate Change” when the “Climate Scientists” start getting some predictions correct. I have had a standing offer for many years to exchange my house in Western Sydney (safely far from sea level rise) for a house roughly the same size on a Sydney beach … just to prove I’m not that worried about those predictions where we all get swamped by the ocean. Strangely no one takes the offer, possibly because the market rate for houses on a Sydney beach is generally several million dollars … clearly not a lot of other people believe it either. Al Gore bought waterfront property, as did the Obama family.

I’m happy to be against forced labor mostly out of principle, rather than buying into the CO2 mythology. It’s a broad topic though … there’s people who believe that paying less than minimum wage automatically becomes “forced labor” and they start talking about bargaining power and things you can’t easily measure. Other people consider all tax to be “forced labor” and there’s a logical connection you must admit.

It also makes sense for resources (including labor, land and minerals) to be priced correctly … but every pricing system includes a lot of assumptions under the hood, such as how property rights work, who can defend their land and resources, what counts as “force”, and what exactly is “consent” anyhow? I’m not much of a believer in the “natural rights” theory … there’s aren’t a whole lot of rights visible in the natural world … rights are human constructs that we choose.

It depends. Consider if it were not labelled a tax. If one person, let’s call him Bruce, forces another person, let’s call her Alice, to work, on threat of he will whip her with a chicotte if she doesn’t, this is forced labor. She is being forced to labor on threat of being whipped. This is how the head tax worked in the Belgian Congo, so that tax was forced labor.

But suppose Bruce doesn’t force Alice to work. She is free to choose her own profession, or to be unemployed if she so wishes. But if she does work, Bruce demands 30% of her income, and if she lies about her income he threatens to imprison her. But if she doesn’t lie about her income and simply claims inability to pay, he might harass her a bit and maybe put a lien on her house, but he won’t imprison her. This is not forced labor, because Alice has the choice to work or not, and what work to do if she does work. The theft occurs after she has already chosen to work, of her own free will. This is how income tax works in the United States, so that is theft (at least from the perspective of people who don’t believe the government has a right to do so), but not forced labor.

Suppose Bruce doesn’t threaten to whip Alice if she refused to earn an income, but he does threaten to kick her out of her home, or to sell her home to a landlord who will then kick her out. She is free to refuse to work to the extent that she can choose to be homeless instead. This is borderline. I believe the definition of sl***ry used by Kevin Bales is that if someone has the freedom to walk away, even if that means starving to death in a gutter, then it’s not technically sl***ry. But forcing someone to work on threat of taking their home away is a sort of forced labor, is it not? I generally use the terms “sl***ry” and “forced labor” interchangeably, but this might be where they are not interchangeable, if we accept Bale’s definition. (Also, the Bellagio-Harvard guidelines say something about forced labor only being slavery if the forced labor rises to the level of “control tantamount to possession”, and arguably, if someone has the freedom to escape their situation by choosing to be homeless, then it doesn’t rise to the level of control tantamount to possession, which supports Bale’s interpretation.) In any case, this is borderline enough that some people might say it is sl***ry, and some might say it is not sl***ry. This is how land taxes / property taxes work. It should be noted that, regardless of whether they are technically sl***ry, they can still be quite deadly: in India under British rule, heavy land taxes were linked to famines.

This is also how rent often works, but many landlords have at least some moral claim to demand rent, if, for example, they built a house, or paid the people who built it, and are trying to get paid for that work or investment. But then there are other landlords, e.g. in Ireland during the famine, who obtained the land by conquest or inherited it from those who obtained the land by conquest. While the former sort of landlord is just trying to get paid for their labor or investment, the latter sort is no better than a tax collector demanding property taxes.

I wrote several replies to you that seem to be stuck in the moderation queue. One was regarding cancer, on the blog post “Tyler Cowen’s Expansive Definition of Externalities”. One was here, regarding different kinds of taxes and whether they qualify as forced labor, and one was a little bit up from here, regarding King Leopold II and how some people are still in denial about what he did (as there are still some people in denial about pretty much every major atrocity).

Anyway, if climate change is confusing to you or you don’t believe in that, then forget about that, just for a moment. There is still environmental destruction occurring in many parts of the world on the local level, which can be understood without any knowledge, understanding, or belief in climate change.

For example, if an area is being contaminated with mercury, a toxic element, this is local environmental destruction, which can be understood and acknowledged without any understanding or belief in climate change, yes? Sometimes this happens as a result of gold extraction, and sometimes the gold miners are being forced to work against their will. Think about it: would you want a job where you poison yourself and your neighbors with mercury? Now, maybe if you are very desperate, you might want that job, I do not claim that all artisanal gold mining is done with forced labor, but then there are also a lot of people who actually don’t want to poison themselves and their neighbors with mercury, and they are being forced. And of course there are some complications, someone might to it voluntarily initially and then not be allowed to leave when they want to leave, and not only that but their children or other next of kin can be forced to stay as well and continue working even after the father is dead. And there’s more complications, like how ens***ers often lure people into various forms of forced labor, including gold mining, is with a bunch of lies and fraud, and then it’s not until the workers finally wise up and realize that they are definitely victims of fraud that the physical force part of forced labor comes in.

Anyway, the link between gold mining and forced labor in Ghana is discussed in Chapter 6 of Blood and Earth by Kevin Bales.

To quote one paragraph from that,

It is understandable that you do not listen to Congolese environmentalists/abolitionists: they are extremely oppressed, so listening them takes extra effort. They are so oppressed that they cannot even be named without exposing them to death! Aside from the human tragedy of it all, the amount of excellent philosophy that is being lost to humanity because these people cannot freely share their thoughts to the world is truly mind-boggling.

However, there are people, such as Kevin Bales, who have done their best to try to see what these people are doing. See the following quotation from Chapter 2 of Blood and Earth.

Looking at the paper, maybe I misunderstand it, but it doesn’t even look like he’s talking everything governments do, just carbon tax, which is insignificant compared to all the land thefts, murders, etc that occur in both first world and third world countries (more murders in the third world countries, but land thefts in both types of countries).

Furthermore, when he discusses the social cost of carbon, it doesn’t seem to discuss the true social cost of carbon, just the portion of the social cost of carbon involving climate change. The true social cost of carbon should also include all said land thefts and murders, the gas flaring in Nigeria, all the water pollution, air pollution, destruction of agricultural and residential land from said water and air pollution, etc. In short, carbon extraction is a way for rich people (rich people in global terms, regardless of whether they identify as rich, which they might not be relative to their neighbors) to get richer at the expense of third world people (as well as some unfortunate landholders who happen to reside in first world countries but get screwed over by various versions of eminent domain for oil/gas companies).