Timeless Profits

(That’s a clever title once you realize the true purpose of my exercise.)

In two previous posts (one and two), I claimed that there is something really fishy in how economists typically solve “the firm’s problem.” Namely, they have the firm maximize the absolute amount of money earnings, but don’t take into account the implicit interest cost on the financial capital invested. Specifically, I reproduced a practice exam question the Texas Tech students had been working on, which featured a corn farm vs. a wheat farm.

I’m not going to spell out the whole thing, and my attempted solution; that will be in a journal article I write up. But I had first wanted to make sure I wasn’t attributing to other economists some personal failing on my part.

Now to be sure, there’s nothing mathematically wrong with how economists have been modeling things. But Steve Landsburg says matter of factly that economists assume that workers get paid immediately out of the proceeds of sales from their output; that’s obviously not true. And I don’t think it’s a harmless assumption, I think it makes economists misunderstand what the owner(s) of a firm are actually doing, economically. (In this respect it’s analogous to my critique of the one-good model and how economists “solve” for the real interest rate by setting it equal to the marginal physical product of capital. Yes, the math works in that unrealistic model, but it gives you bad economic intuition.)

Anyway, commenter “baconbacon” claimed I was making a really basic mistake in my analysis, and challenged me to show what would happen if the workers offered to wait until harvest time to get their pay.

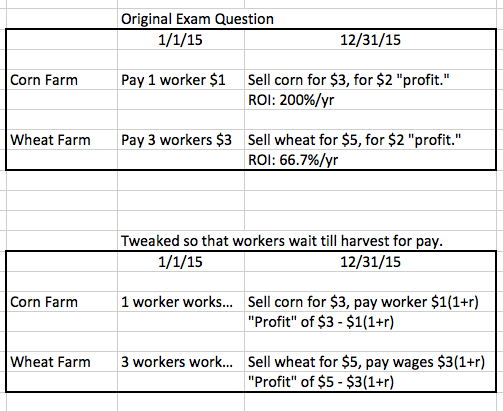

I have to be brief (since I have a day job) but here are the figures. Note, I am retaining the original numbers for the corn farm from the exam question, but I invented (for simplicity) the numbers that make the wheat farm have the identical “profit.” (I’m putting “profit” in quotation marks since I want to highlight that that may not be the right term, since we’re ignoring interest.)

So here you go:

Now in the original exam question version, my point was that the “correct” answer for the corn and wheat farmers’ optimization problems, has them both earning $2 in revenues-costs, where costs are taken to be the wages paid to the workers. (Landsburg and others agreed with me that that was the “correct answer” to this question.)

But I pointed out that if there is a time lag, then it implies a higher rate of return to the corn versus the wheat farmer. I just made up the fact that it’s a one-year lag, but surely with agriculture we can’t ignore the fact that there is a time lag.

So in that context, I took baconbacon to be claiming that I would see my mistake if I had the workers wait to get paid; if their wages came right out of revenue, then my (alleged) confusion would vanish because there would be no period of invested financial capital. It would not be an issue of “return on investment” but instead would be a simple matter of maximizing the total number of dollar bills in your hand, free and clear, on December 31, 2015.

OK great, I’m happy to play that game. In the second scenario above, we see that the workers defer their payment in order to earn r% interest on what would have been their original paychecks. Thus the corn farmer pockets net income from the deal of [$3 – $1(1+r)], while the wheat farmer pockets [$5 – $3(1+r)].

So, my job is to show that even in this version, it is clearly better to be Farmer A. Thus I want to show that the first expression is bigger than the second, or (equivalently) I will show that the first expression minus the second, is always positive.

Thus the advantage to the corn farmer is given by

$3 – $1(1+r) – $5 + $3(1+r),

which equals

$2(1+r) – $2.

So, can we say that this expression is positive? Yes we can, so long as r>0.

And that makes perfect sense, lining up with my initial intuition. If there is any opportunity cost of tying financial capital up for a period of time, then it is more profitable to be a corn farmer than a wheat farmer. Changing when the workers get paid doesn’t alter that fact, just like paying them in quarters instead of dollars wouldn’t alter which operation is more profitable.

THE IMPORTANT LESSON: Some may have thought Steve Landsburg was arguing that as long as workers happened to get their paychecks at the moment of final sale, then that is sufficient to rescue the traditional approach. However, as I’ve just shown, the actual requirement is that a worker’s output immediately yields the finished product. It’s not the lag between a worker’s paycheck and the final sale that’s the issue. Rather, it’s the lag between the input of worker labor and the physical yield of the output good.

In general that is clearly wrong, and in particular it’s absurd to make that assumption when you’re modeling agriculture. And I don’t think it’s a “harmless” assumption made for “mathematical tractability.” I think it teaches us the wrong intuitions and concepts of how the economy actually works.

Bob

The cost of labor in the equation is defined as paid “at the time of harvest”. If a worker wants to be paid 1 year prior to the harvest he has to take a lower wage to do so, with the difference equal to the interest rate. Wages then = 3(1-r) if paid in advance.

This makes sense if you have a simple model, just seed corn, land and labor, and payment being made in corn. With no savings labor cannot be paid prior to harvest and so any agreement on payment takes the form of at the date of harvest. If you introduce savings then it is obvious that the holder of capital (ie the saver) is the one who must be paid the interest rate, so when the laborer tries to get his pay early the saver only does so at a price.

baconbacon you can go back and look at when I said, “OK I’ll agree to do this, but only if you agree that you won’t tweak your critique.” I put in huge capital letters what I was gong to do, regarding the assumption about timing and physical output, etc.

I did exactly what I said I would do, and you agreed it would be decisive. And yet, you still seem to think you are right.

I’m sorry that is your view Bob my critique, in my view stays the same. Your use of the term “ROI” is lumping in labor with capital, which is my original critique if you go back to the restaurant example. My reply above is an attempt to distill that to direct language to respond to this post here. Again, take the simplest model-

1 landowner has 1 acre of land. One worker negotiates, he will work the land in exchange for half the harvest. At harvest time there are 4 bushels of wheat, so the landowner gets 2 and the worker gets 2.

A. Given the above agreement if the worker asks for advanced payment will the landowner agree to pay more than, less than or equal to the 2 bushels of (expected) wheat?

B. How would you express the landowners ROI in terms of the original agreement?

baconbacon,

Agriculture laborers are not paid in corn or wheat. They are paid in dollars, and those dollars come from the employer for the purposes of harvesting the corn and wheat, which are subsequently sold to the buyers of the corn and wheat. The buyers don’t pay the laborers, they pay the owners. By the time the owners are paid for the output, the laborers have already performed labor and were already paid for it.

This notion that laborers are paid in the product is not what happens in the real world.

*sigh* baconbacon right, which is why your original request to transform the problem was valid. I went from showing how if we use money, and pay workers upfront, then there is a higher ROI on corn farming.

You said if we got rid of the initial money investment, and just did payment out of the output, my confusion would go away.

So I transformed it. The corn farmer makes more money than the wheat farmer. You are just ignoring that fact in my second example above, as if that’s no big deal. So I took out the ROI, and made it purely about which operation gives you more profit at the end moment. Corn beats Wheat, so clearly it’s not correct when we say they are equally profitable.

Bob- you (unintentionally i believe) changed the original problem to do so.

The cost of labor is defined in that scenario as paid at harvest. In your example you move the cost of labor to 1 year prior to harvest but define it as the same cost.

You are an Austrian, right? What is interest paid on in the Austrian school? Is it savings? Who has the savings in this scenario? The guy paying wages BEFORE harvest can only do so through savings, but you are paying the laborers who have no savings (in this model) the interest rate

The workers aren’t being paid in advance in the tweaked scenario? they are specifically deferring payment until harvest (which is an arbitrary time period later). Why are you saying that they get paid in advance?

@Michael-

In the original proposition the value of their labor was the cost at the time of harvest. Bob took that same cost and shifted it to pre harvest, and then added interest to come up with the at harvest cost.

“If a worker wants to be paid 1 year prior to the harvest he has to take a lower wage to do so …”

In case anyone missed it, that’s just another way of saying what Bob said:

“In the second scenario above, we see that the workers defer their payment in order to earn r% interest on what would have been their original paychecks.”

*Takes a bow*

“In case anyone missed it, that’s just another way of saying what Bob said:”

It isn’t because the original question defined wages at the time of harvest.

1) I don’t see a big hairy deal with the “correct” answer. What the question is trying to do is see if the student understands that firms can discover their profit maximizing level of output by increasing output till the marginal cost is the same as the market price. The problem gives a really stripped down cost function just so the math is easy. One would hope that micro 101 would at some point teach that real world cost functions will include all kinds of stuff including the cost of credit.

2) Everywhere I’ve worked (manufacturing) workers were paid in arrears. Granted, pay periods for direct labor are only two weeks at most but there is still some period where it is posible for firms to pay workers from output with no cost of credit involved.

I do agree that the choice of agriculture was unfortunate because of the time delays involved. Cash only fast food joints would have better.

Capt. Parker, that’s why I asked people to give their credentials. PhD economists said what “the correct” answer was.

Nowhere in typical, formal economic models do they deal with the fact that you pay workers upfront and then get the product in subsequent time periods.

Or, to be more specific, that there is a lag between the input of labor and the sale of the product.

Yes they do, its called the interest rate.

In row crop agriculture farmers take out annual lines of credit to cover their input costs, term loan principal payments, and family living expenses. These lines of credit are paid off at harvest and renegotiated annually.

In times of low crop prices or yields, farmers often have to refinance these lines of credit into term loans which can be problematic in times of declining asset prices. The 1980s farm crisis is a good example of this.

Your theoretical argument certainly manifests itself in the real world.

Armen Alchian’s RAND article from 1958 might be of interest to readers and may even be a good reference for your article, Bob.

http://www.rand.org/pubs/papers/P1449.html

thanks I’ll check it out.

There is some difference, in as much as if the workers are paid late, then the cost is carried by the workers and not by the firm owners. However, at the same time (in this particular problem) wages are fixed, and workers cannot choose who they work for. Thus, they carry the cost, but no choice the workers make can alter this outcome.

There’s also another strangeness about the problem as stated which is that it isn’t supposed to be possible to just create more and more corn farms. That is, a given owner can strictly own one corn farm or one (much larger) wheat farm… and that’s just silly. Why not own two, four or a hundred corn farms? Then you can achieve profits of a similar level to the wheat farms… and also get a good return on investment if you find yourself tying up capital.

The whole thing is an exercise in arbitrary and unrealistic equations IMHO.

Although there’s no universally accepted scale of wrongness when it comes to teaching intuition, I still put forward the viewpoint that having fixed prices is by far the biggest unrealistic assumption. This should deeply bother any Austrian economist because price fixing completely destroys any possibility of price signalling in the process of reaching equilibrium.

It’s even more astounding when the problem as stated allows for massive shifts in the volume of both goods produced and labour, while insisting that prices remain fixed.

I absolutely agree with you that the “official” answer assumes that labor and production are simultaneous.

I absolutely agree with you that in the absence of that assumption, the official answer is wrong.

I absolutely agree with you that the key assumption has nothing to do with lags between working and getting paid; instead it has everything to do with lags between working and producing output.

I can’t imagine you’ll get any serious disagreement about any of this.

Thanks Steve.

I think this is about as clear as I can be.

If you have the wages at time of harvest + the interest rate you can figure out the wages paid at any time prior to or even later than the harvest. If they get paid before harvest the get w(1-r) if they get paid after harvest they get w(1+r). If you start from this point there is no way, at equilibrium, to gain more money by switching from corn to wheat or vice versa.

Baconbacon: Are you assuming that the labor is physically applied at the moment of harvest? That’s what the issue is here (as Steve Landsburg agrees). The timing of the payment is irrelevant.

We can do it in terms of physical units. If you give one unit of corn to a worker at t=1, and then at t=2 his efforts have yielded three units of corn, whereas you give three units of wheat to workers at t=1 and then at t=2 their efforts produce 5 units of wheat, *and* if we assume that a unit of corn has the same market value as a unit of wheat throughout, then my point still stands.

@Bob

Again, the original problem was stated as payment at the time of harvest, it doesn’t matter when the labor happened. For example

Worker agrees to work for one unit of corn, paid at the time of harvest. Worker changes his mind and asks for payment now. Payment now = ~0.91 units of corn (assuming a year lag and a 10% interest rate).

Worker agrees to 3 units of wheat, paid at the time of harvest. Worker changes his mind and asks for payment now. Payment now = ~2.7 units of wheat.

Profit ends up the same if they all get paid at harvest time, but if payment goes at planting time then the wheat producer earns “more” profit, but with that profit being exactly equal to the opportunity cost of tying up the extra capital.

Bob: Probably the cleanest way to handle this is to discount the value of the corn and/or wheat back to the day on which the labor is applied. So if you’re hiring labor today and you expect to produce wheat that can be sold next year for $2, you should say that the price of wheat is not $2, but $2/(1+r)$. I’m not sure whether there’s some Austrian objection to that kind of discounting (I say this by way of reminding you just how ignorant I am about Austrianism), but surely that’s what a “mainstream” economist would do.

Steve, great, that’s exactly what an Austrian would do. So you’re not paying the worker for (finished future) wheat, you’re paying him today for (unfinished present) thing-that-will-turn-into-consumable-wheat. And yes, if you make that assumption, then the problem disappears because then there’s no time lag between the input of labor and the output of physical product.

But that’s not what happens in the real world, and it’s not what 99.999% of economists and econ students think is happening in their models.

By the same token, we can assume that all labor is performed by reproducible robots, and then we’d correctly teach our econ majors that in equilibrium, r=MPL. Then some purist might object and say interest rates really aren’t “about” the marginal product of labor, but I could show him how it’s right in the model if we make that unrealistic assumption.

“But that’s not what happens in the real world”

This is what happens in the real world. Workers that get paid in advance of production must be getting paid out of savings. They logically must be paying an interest rate to get their pay in advance in an efficient economy.

baconbacon,

I don’t understand what is going on here. Yes, of course they must be paid out of savings. And so the saver would not settle for a ROI that is lower in one line than in another.

Or, if we have the workers wait for their pay, then the workers are implicitly saving. If we assume they get the same interest rate in each line (otherwise why would they work for the employer offering the lower one?), then we see that one line gives a higher profit than the other.

” they have the firm maximize the absolute amount of money earnings, but don’t take into account the implicit interest cost on the financial capital invested.”

If you imagine the firm as a purely entrepreneurial entity that owns no capital then it will always want to maximize the absolute amount of money earnings and not care about ROI. If corn production takes a year and the workers need to be paid in advance then the firm will have to borrow the money at interest, but this is just a business cost from the firms perspective that will have to be deducted from profits.

It is owners of capital who care about ROI, and this will cause ROI to be equalized between product lines. This will cause the production of the 2 goods to move to optimal levels in the economy (but is beyond the scope of the test question).

It may be that some firms also own capital, and in this case their activities need to be separated into investment decisions (where ROI will be relevant) and entrepreneurial decisions (where absolute profit will be relevant). In the test question it seems implicit that firms own no capital.

If production takes a year as in Bob’s example then we have to assume (since interest rates are not part of the production function) that workers wait until the good is sold before getting paid then in effect it is they who are savers. and get a premium on their wages for waiting until they are paid.

Bob,

“I don’t understand what is going on here. Yes, of course they must be paid out of savings. And so the saver would not settle for a ROI that is lower in one line than in another.”

Again the original conditions of the problem are that workers are paid at the time of harvest, which means that the labor cost INCLUDES the interest rate you are paying to the laborers for their “savings” (if that is how you want to approach it).

You shifted the labor cost one year earlier without subtracting out that (implied) interest, and so made labor more expensive than in the original. If you used the above as a starting point then the cost of labor would go from $1 per worker to $1.10 per worker and would shift the equilibrium.

The original problem gives you

1 The cost of labor at the time of harvest

2. The interest rate

From those two you can calculate the cost of labor at any time prior to or after harvest. If you pay labor at 1 year prior to harvest it costs ~$0.91 per worker, not $1 as you stated above.

I think that it is the assumption that prices are fixed (and all firms price takers) rather than the assumption that wages are not paid until revenue is generated that drives the outcome where production levels would be non-optimal.

If you assume instead that prices fall for each commodity as output increases then I suspect it makes no difference when wages are paid.

An optimal outcome would be one where prices are such that markets clear when everyone buys quantities of corn and wheat such that their last purchase of each yields equal utility. For any given pair of production functions there will be different levels of output of corn and wheat depending upon prices. But there will be only 1 set of prices that is also optimal (as just described) and prices will tend to move towards these if they are set by the market. I think this will still mean that all firms have equal absolute profit , but it will also be the same set of prices and output levels that would be arrived at if wages were paid in advance and firms had to pay interest.

And from a workers perspective the supply of labor will depend upon real wages, which will be adjusted for the point in time where wages are paid. If wages are flexible a firm will have the choice between paying a interest-adjusted wage later or a lower wage earlier if it wants to attract the same qty of labor.

This is my same approach to the problem, but in this case wouldnt the distribution of labor just adjust in equilibrium?

I thought your point was that first should equalize ROI (in your tables above). if there is more factor adjustment? labor would just go to the corn famers until absolute profits are equalized.

“In the second scenario above, we see that the workers defer their payment in order to earn r% interest on what would have been their original paychecks. Thus the corn farmer pockets net income from the deal of [$3 – $1(1+r)], while the wheat farmer pockets [$5 – $3(1+r)].

So, my job is to show that even in this version, it is clearly better to be Farmer A”

In this case it would also be better to be farmer A if they paid the wages earlier, they would simply pay interest on the money they borrow of $1(1+r) or $3(1+r) and this would diminish profits by differing amounts just as in your example, making farmer’s A profits greater. This would render the answer to the test question incorrect.

I think baconbacon’s point is that if you start from the given answer and assume this is with wages being paid when the crop is sold, then if you move the point where wages are paid backwards in time and reduce them by r, you maintain the original solution to the problem (profits are given by [$3 – $1(1+r-r)] and [$5 – $3(1+r-r)] and are always equal for both farmers, that is: profits increase as wage payments decrease, but this is cancelled out by the fact they pay an exact equal amount in interest payments on money borrowed to pat those wages)

I call this one for baconbacon.

Transformer do you agree with this summary?

BOB: This question is messed up, because it assumes there is no lag in output even though it’s agriculture.

BACONBACON: Right, but if we assume there’s no lag in output, the question works.

TRANSFORMER: I call this one for baconbacon.

No.

I think you can make the question work with a lag in output. You just have to assume that the workers are being paid a premium for waiting until the crop is harvested over what they would get if they were paid earlier.

As long as you reduce wages by r as you go back in time (and assume farmers borrow at r to pay these wages) then corn and wheat farmers continue to earn the same absolute profits no matter when wages are paid.

And in fact in your example (if I understand it correctly) if you take into account that if wages are paid later and wages are higher, then these higher wages are matched by either avoided interest payments that farmers would have to pay if they pay wage early or foregone interest payments if they paid wages early out of their own savings.

Once this is done the absolute profits made by both farmers are the same whether wages are paid early or late.

Bob,

You say “I’’m not going to spell out the whole thing, and my attempted solution; that will be in a journal article I write up.”

Are you still planning that ?

I still think that baconbacon (and I, once I understood what he was saying) have a valid point that the original question can have the same answer for both “production is instantaneous” and ” production takes time, and wages reflect a premium for savings by workers” scenarios that I do not think you have fully addressed in your responses to either him or me.

Transformer wrote:

I still think that baconbacon (and I, once I understood what he was saying) have a valid point that the original question can have the same answer for both “production is instantaneous” and ” production takes time, and wages reflect a premium for savings by workers” scenarios that I do not think you have fully addressed in your responses to either him or me.

Can you please spell out just this point? I agree that I haven’t acknowledged that you guys have shown these two scenarios are equivalent, but that’s because I don’t think you’ve shown that.

Do you agree that the two operations are NOT equally profitable to the owner, in the example I gave? But notice if production were instantaneous, then they would be, because there would be no time for the capital to be invested and so the implicit opportunity cost of tying up the capital would be zero.

Assumptions:

– Production processes involve only labor and time (no land or capital)

– Farmers have no money of their own and just co-ordinate production and sell output

– Farmers aim to maximize absolute profits in any given time period.

– Farmers have to borrow at the given interest rate any money needed in the production process.

– r = 10%.

Case 1. Production is instantaneous.

Corn: Wages $1, Revenue $3 = $2 profit

Wheat: Wages $3, Revenue $5 = $2 profit

In both cases “profits” are equal at $2, just as in the test question.

Case 2. Production takes a year, wages are paid after revenue is obtained,

Corn: Wages $1, Revenue $3 = $2 profit

Wheat: Wages $3, Revenue $5 = $2 profit

Note: The is the same as case 1. The workers are in fact getting a 10% premium for waiting a year for their wages, but that is not explicit in the accounting.

Case 3. Production takes a year, wages are paid at start of year. In this case wages will be 10% less once the premium is subtracted, but as the farmers now have to borrow the money to pay the wages they also have to pay interest

Corn: Wages $0.91, interest 0.09 Revenue $3 = $2 profit

Wheat: Wages $2.73, interest 0.27, revenue $5 = $2 profit.

In all 3 cases the profit per period is identical.

I think what is wrong with your tweaked example is as follows.

– You take the $1 wage as being paid a year ago and then use r to calculate what the wage would be if the workers got a premium for waiting. This leads to corn farmers and wheat farmers making different absolute profits

– However you do not factor in that farmers would have to pay additional interest in the case where they pay lower wages earlier.

– Once that is factored in profits in both your scenarios will be the same for each crop in each period, but different between crops for both periods.

Your scenario 1 (adjusted to include interest of 10%)

Corn: Wages $1, interest $.1 Revenue $3 = $1.9 profit

Wheat: Wages $3, interest $.3 Revenue $5 = $1.7 profit

Your scenario 2:

Corn: Wages $1.1, interest $0 Revenue $3 = $1.9 profit

Wheat: Wages $3,.3 interest $0 Revenue $5 = $1.7 profit

I hope this explains my point and I have made some basic logic error , or misunderstood the issue, somewhere.

Thanks for putting it clearly like this Transformer

I have NOT made some basic logic error , or misunderstood the issue, somewhere.

You wrote:

This further reduces to: $2r.

Bill Drissel

Frisco, TX