Structural versus Demand-Side Theories of Unemployment

Paul Krugman has a new post–which Scott Sumner calls “very good”–in which he explains why the structural explanations of the recession don’t fit the facts. In contrast (you will not be surprised to hear), Krugman’s own demand-side theory comes out with flying colors. Here’s Krugman:

[O]ne strong indicator that the problem isn’t structural is that as the economy has (partially) recovered, the recovery has tended to be fastest in precisely the same regions and occupations that were initially hit hardest. Goldman Sachs (no link) looks at unemployment in the “sand states” that had the biggest housing bubbles versus the rest of the country; it looks like this:

So the states that took the biggest hit have recovered faster than the rest of the country, which is what you’d expect if it was all cycle, not structural change.

Now this is very interesting. I recall Krugman back in December 2008 making fun of the “structural unemployment” theorists by writing:

One striking fact, which I’ve already written about, is that the current slump is affecting some non-housing-bubble states as or more severely as the epicenters of the bubble. Here’s a convenient table from the BLS, ranking states by the rise in unemployment over the past year. Unemployment is up everywhere. And while the centers of the bubble, Florida and California, are high in the rankings, so are Georgia, Alabama, and the Carolinas.

Now even at that time, Krugman’s analysis was goofy. I pointed out that looking at year-over-year changes in unemployment at the end of 2008 was hardly the right test. If we looked at changes from the moment the housing bubble burst, then five of the six states with the biggest housing declines were also in the list of the six states with the biggest increases in unemployment.

So let’s review: Back when Krugman thought that the data showed no obvious connection between the collapse in the housing bubble and unemployment rates, he was happy to say that the structuralists were wrong, and only his generic demand-side story made sense.

Now, four and a half years later, Krugman readily admits that unemployment shot up more in the housing bubble “sand states” than in the rest of the country when the recession first struck. But because unemployment has fallen more sharply in these states amidst the recovery, he tells us that this is just what his demand-side story would predict. The structuralists, he tells us, can’t explain it.

That seems a bit convenient to me. One almost gets the sense that Krugman first looks at the data and then decides what his demand-side story predicts.

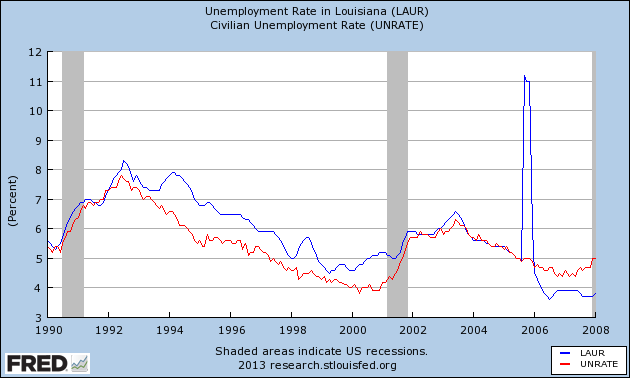

In any event, let’s apply this new, smashing argument against the structuralists to an earlier U.S. recession. Does everyone remember the downturn in the labor market of late 2005? Let’s go to FRED to refresh our memories:

As you can see, both the national and the Louisiana unemployment rates increased in late 2005. Now some of us Austrian and Real Business Cycle theory types wanted to blame it on a supply-side, structural problem–would this count?–that interfered with workers, employers, and consumers being able to interact with each other as smoothly as in 2004.

However, it’s obvious from the chart above that the state hit hardest by the shock was also the one to recover the most quickly. Thus, as Krugman and Sumner tell us, this is quite compelling evidence that people in the US in late 2005 for some reason decided to stop spending enough money, and moreover they must have been really antsy about buying things made in Louisiana.

I would have thought that if there’s any difference between one group of states and another group of states, based on relative distribution of economic activity … then is has to be structural. Of course, in this context “structural” could mean a lot of things, including legal difference, “right to work” legislation, business friendly environment, and a bunch of other stuff.

How exactly does the “aggregate demand” theory explain any difference between states at all?

I might point out that the “structural” adjective means a different thing to Keynesians than what it does to Austrians. From an Austrian perspective, “structural” means pertaining to the structure of the economy (a bit like what the dictionary says), from a Keynesian perspective “structural” means anything that doesn’t go away in one cycle, possibly caused by the underlying structure of the economy, or possibly not but anyway, who cares, shut up if you disagree. Those divergent uses of language probably give rise to additional confusion.

How exactly does the “aggregate demand” theory explain any difference between states at all?

It didn’t, back in 2008, when Krugman thought the data didn’t show a clear difference among the housing and non-housing bubble states.

But now that there is a clear difference, apparently Krugman’s theory is just the ticket to explain the observations…

“How exactly does the “aggregate demand” theory explain any difference between states at all?”

It explains it thus: Demand fell more in some states than others for some reason.

That isn’t aggregate demand. That is relative demand (between states).

Aggregate demand fell in such a manner as to produce relative differences of the degree of the fall depending on which arbitrary border one finds themselves in.

Bob why shouldn’t data from late 2008 be the right test. The housing bubble burst before the beginning of the recession., yet unemployment only started to accelerate in late 2008. Thats evidence in favor of Scotts view, not yours, that the recession was caused by falling NGDP, not the housing bubble. So counting the unemployment decline from the moment the bubble burst is hardly the right test, because bubbles can burst in one sector without destroying the rest of the economy, (The internet bubble)

That’s incorrect.

Structural problems do not have to manifest in only a change to the distribution of an unchanged nominal demand.

Structural problems can, and almost always do, manifest in changes to aggregate demand as well. This is due to the fact that people are independently thinking and acting individual entities.

If there is a structural problem, and too many houses and office buildings and not enough other goods are being produced, then it does not follow from a period of rebalancing that any fall in spending in housing should be exactly matched by rising spending on other goods. It takes time to produce new goods. If resources and capital are going to be reallocated to other industries, away from housing, then that rebalancing does not have to be in a context of unchanged aggregate nominal demand. Aggregate nominal demand could very well fall, as spending in the housing industry decreases, housing workers reduce their spending, which changes the relative profitability between housing and everything else.

There is no such thing as an aggregate demand problem. It is a figment of the imagination, built on the false assumption that the real economy is supported, or driven by, total exchanges of dollars. In reality the economy is driven by relative spending, relative prices, relative allocations of real resources, relative allocations of capital, and relative allocation of labor.

For an economy distorted by previous inflation, should individuals raise their cash preference such that not only relative spending, but aggregate spending falls, then this is the market telling you that there have been errors in investment, and that any resulting aggregate deflation is the only way to reveal which investments should be re-allocated, and which ones should not. If this means a LOT of investments have to change, if this means a LOT of labor has to be reshuffled, then that just means that the market is telling you that there have been a LOT of previous malinvestment.

Bob, you’ve got to get a ‘rec’ button to click for posts like this.

MF,

Beautifully described.

“Thats evidence in favor of Scotts view, not yours, that the recession was caused by falling NGDP,…”

(bold added)

>> Can you elaborate on the section I emphasized? At first glance, this reads like someone saying the stormy weather outside is caused by the rain. No, it’s stormy because warm air rose, cooled, condensed, and fell back down as rain. The conditions that created the atmospheric instability is what caused the storm, of which rain is merely an observable manifestation. The recession is not caused by falling output, it’s defined as falling output. The nominal component is just smuggling in an inflation bias. I’m sure you have something else in mind here, so can you help explain what you mean by that?

Aren’t all problems in economics “demand-side” problems? You made a bunch of stuff to sell or you want to make a bunch of stuff to sell and, for some reason, no one wants to or will buy it.

When pressed, the inflationists tend to claim that it is possible in principle for there to be structural problems, and from time to time they may even grant a non-zero causal explanation of economic problems to structural imbalances.

But when making unsolicited arguments about the cause of historical economic problems, 99.9% of the time it’s “demand side” problems.

As if people are “supposed to” demand X; which implies an odd definition of “demand”.

Yeah, “demand *what*?” is the question they fail to ask…

I really don’t get what the exact demand problem is supposed to be. It sounds like people actually have the demand (in the proper meaning of having the desire and the purchasing power) but for whatever reason (maybe some irrational uncertainties) they don’t apply this demand and hoard their money instead. As a Keynesian and market monetarist you obviously can figure this situation out by just comparing GDP and unemployment from last year to this year. Yet I completely fail to see how they know that it is irrational uncertainties people have and not rational reactions to a supply problem (wrong structure of capital). Since at least in theory both problems would make GDP and employment go down. So how do they actually know?

If they really could do that they would be the best investors in the world in my view, since I thought it is investors and entrepreneurs who see supply problems and exploit them.

And do all people have those problems to the same degree? It is a bit like saying: Huu, we have many people with cancer in the economy so, let’s just give all people a chemo therapy (this even grants that the cure prescribed is even effective against the supposed diagnosed disease, which I doubt as well! And the diagnose of cancer is based on the sole fact of: More people are dying this year than last.)

It has always been a beg the question fallacy, in my humble opinion.

Yes, the problem is they hoard their money. Because it should be forbidden to save more than a prescribed and constant amount, due to changes in uncertainty or life events. Or just maybe you like dollar bills or something. Who cares – the problem is you are not demanding what you should be demanding!

You are onto something there.

If it wasn’t for the outrageous demand side problems our economy faces, I should be getting paid for laying in a hammock all day drinking beer. I’m 100% willing to do the job, the fault lies with the weak demand.

Silly Tel, the demand side story is far more sophisticated than that.

You have to imagine everyone lying in their hammock all day long drinking beer, and then, after “demand” collapses, can you then legitimately blame “insufficient demand”.

If it’s just you in the hammock, then the “demand side” folks can safely admit that you aren’t making what you thought you would make because of the relative value of your activity. They can protect the “insufficient demand” in these cases.

For that magical intellectual void space in between you doing something valued less than expected, and a lot of people doing something valued less than expected, well, you’re not supposed to inquire about that. We can only deal with one or a few people making less money, and everyone making less money. The former can be relegated to a real problem, but the latter is a demand problem and has to be “fixed” by “stimulus” for activity as such, even if it is lying in a hammock all day.

Better that than not working and figuring out something productive to do. That’s just evil.

Don’t think, just “move.” Keep moving, so that you keep paying taxes.

Hey buddy, quit crowding my market. I’m getting a union together because the public deserves quality drunks, not shonky fly by night lightweights. Someone has to keep up standards you know.

If it wasn’t for all that Austerity out there, I’d be creating jobs by now. Just lend me the money (at zero interest) and I’ll be paying some babe to bring me cold beers. Fixing an economy is easy as piss, speaking of which, I just came up with another job creation scheme.

Sorry, not a union, a professional association, known as The Job Creator’s Club.

Scott’s post is head-shaking.

It is amazing how he falls for Krugman’s central argument that because those industries and geographical locations hardest hit during the recession were the quickest to recover out of the recession, this is somehow evidence that it’s a demand problem and not a structural problem.

But that is exactly what we would expect if there is a structural problem. Deflation does tend to hit those industries most sensitive to inflation the hardest (that’s structural), and so another round of inflation after that deflation does tend to affect those same industries again the hardest, such that we see the fastest “recovery” in those industries and areas once again (structural again).

As with everything economics, and this is not exactly a criticism, but one really does see in the data what one wants to see. If one wants to see a demand side problem, it will appear to be there somewhere.

” If resources and capital are going to be reallocated to other industries, away from housing, then that rebalancing does not have to be in a context of unchanged aggregate nominal demand. Aggregate nominal demand could very well fall, as spending in the housing industry decreases, housing workers reduce their spending, which changes the relative profitability between housing and everything else.”

Nobody said AD would be UNCHANGED, just not a complete collapse of other sectors. And you’re missing the point as usual. There doesn’t have to be an IMMEDIATE boom. What the structuralists have to answer is why the bust in other sectors is so great.

Also when you say “rebalancing does not have to be in a context of unchanged aggregate nominal demand. Aggregate nominal demand could very well fall, as spending in the housing industry decreases, housing workers reduce their spending, ” you’re invoking demand!

“Nobody said AD would be UNCHANGED, just not a complete collapse of other sectors. ”

Nobody said aggregate demand “collapsing” versus aggregate demand “falling somewhat” had any fundamental point against the structural theory.

“And you’re missing the point as usual. There doesn’t have to be an IMMEDIATE boom. What the structuralists have to answer is why the bust in other sectors is so great.”

Because capital investment is inter-related. A pencil requires not only retail stores that sell them to consumers, but it requires the wood industry, the mental industry, the paint industry, the graphite industry.

Imagine an incredibly complex single factory that produces pencils from scratch. If one stage in the process gets out of whack, then it should not be surprising that the entire production line of pencils is negatively affected.

It would be silly to believe that if the graphite subsidiary of the company had problems, that the other subsidiaries would be able to make more of their respective materials, without having any effect on pencil output.

What the “aggregate demandists” have to explain is why do the capital intensive, interest rate sensitive industries suffer so much more, relatively speaking, than the less capital intensive, less interest rate sensitive retail and service sector industries, given that investors are profit seeking, forward looking individuals who understand inventory, cash flows, and so on?

“Also when you say “rebalancing does not have to be in a context of unchanged aggregate nominal demand. Aggregate nominal demand could very well fall, as spending in the housing industry decreases, housing workers reduce their spending, ” you’re invoking demand!”

It’s not “invoking” demand as a CAUSAL explanation Edward. It’s an EFFECT of the underlying STRUCTURAL problems that are the actual CAUSE.

By your logic, if a person turns pale because they’re ill, and someone who adheres to the germ theory of disease held that the reason they turned pale is because of their underlying disease, then they would be “invoking” color side problems of sick people, and that they should agree that to fix the ill person’s health, they should have their face painted brown. Then when they remain ill, you exclaim “Their sickness is worse than I thought! We need more brown paint! I told you we went too easy on the paint! But you austerians keep harping on germs this and viruses that. But that’s not empirical! Every time a person gets sick, they almost ALWAYS turn pale, and when they get better, they almost always become more flushed! Stupif dogmatic Austrians.”

Lol

“What the “aggregate demandists” have to explain is why do the capital intensive, interest rate sensitive industries suffer so much more, relatively speaking, than the less capital intensive, less interest rate sensitive retail and service sector industries, given that investors are profit seeking, forward looking individuals who understand inventory, cash flows, and so on?”

Its not clear at all that the capital intensive industries suffer more

Get a clue Edward. It is “clear.” Just because you aren’t looking at history, it doesn’t mean it didn’t occur.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=lc7

“Because capital investment is inter-related. A pencil requires not only retail stores that sell them to consumers, but it requires the wood industry, the mental industry, the paint industry, the graphite industry.

Imagine an incredibly complex single factory that produces pencils from scratch. If one stage in the process gets out of whack, then it should not be surprising that the entire production line of pencils is negatively affected.”

Ever heard of something called “supply chain management?” Any business worth its salt will buy from multiple vendors, so that if one vendor is negatively affected by a supply shock, the business can keep running smoothly

“Ever heard of something called “supply chain management?”

Yes.

“Any business worth its salt will buy from multiple vendors, so that if one vendor is negatively affected by a supply shock, the business can keep running smoothly.”

Since when did the metallurgical industry buy from multiple graphite industry companies in order to “run smoothly”?

And since when did your claim of what firms ought to do to be “worth their salt”, have anything to do with what firms actually do?

I’m not talking about direct supplying of business firms by capital goods stages once removed. I am talking about the whole economy. Despite the fact that not every firm is directly supplied by every other firm, it does not mean that these firms are not inter-connected in terms of dependence on the division of labor to produce the goods that we end up consuming.

“Any business worth its salt will buy from multiple vendors, so that if one vendor is negatively affected by a supply shock, the business can keep running smoothly”

Three companies A, B, and C require aluminum to produce their product. They buy this aluminum from X, Y, and Z, so as to avoid supply shocks. However, the aluminum industry over expanded due to malinvestment, and now company X goes under. Y and Z must pick up the slack for these three companies. However, the reduction in general supply means the price of aluminum increases to a level in which company B can no longer profit, and so it has to scale back to return to profitable production levels. Supply shocks have detrimental effects, whether it be from malinvestment or from natural disasters. Prices rise, and that will cause problems, even if you can get your supply from other firms in the meantime.

“Any business worth its salt will buy from multiple vendors, so that if one vendor is negatively affected by a supply shock, the business can keep running smoothly.”

First, we’re not talking one business, we’re talking “structural”, as in persistent across the entire industry. Second, even if only one business is hit, this still has implications for the entire industry and therefore the entire economy.

And capital investment is not so interrelated that the capital goods required to make say, cars and iPhones, are intertwined. Nope.

If an iPhone store set up shop next to an artificially stimulated car manufacturing plant, and the car plant went under, there would be less demand for those iPhones, as well as all the businesses around the plant that the workers used to frequent.

Then the restaurant workers and theater workers would have less money with which to buy their iPhones.

There would be less demand for iPhones in that area, and there would have to be reduced production with accompanying layoffs.

It all depends on what sectors’ profits are dependent on artificial stimulus. Those who use the new money first get the most benefit from it, but there’s going to be costs that the second user of the new money can socialize onto still later users of the money.

“And capital investment is not so interrelated that the capital goods required to make say, cars and iPhones, are intertwined. Nope.”

They are intertwined, you just refuse to, or are able to, see it.

Those industries that both Apple and GM depend on, connect Apple and GM. Yup.

Edward, this article won’t convince you the empirically the US went through a structural problem after the housing bubble burst, but it will at least show the theoretical basis for such claims. You are making it sound like it’s nonsense on the face of it, and it’s not. (Krugman even admitted that my “sushi model” in this article was theoretically sound, he just thought it wasn’t what happens in modern democracies in recessions.)

You are a saint, Bob. Trying to educate the willfully ignorant like Edward. It’s not that he doesn’t get it, it’s just that if he does ‘get it,’ he’ll have to abandon his cherished fantasies he so desperately wants to be true. Sort of like evangelicals that try and reject evolution because it doesn’t jive with the book of Genesis.

Everyone is capable of changing their minds.

To assert otherwise is to attack reason itself, and if you attack reason, you’ve pulled the rug out from under your own feet.