My Mises Column on the Econ Nobel

Here is my column at Mises today on the new Nobelists. I walk through a watered-down numerical example to give you a flavor of their labor models, in case you aren’t quite able to read the actual journal articles but you want a little bit more meat than I’ve seen in most second-hand accounts.

Then of course I take my marbles and go home to my copy of Human Action, when I say this:

Now, it would be one thing if the problem of long-term unemployment had been a tough nut to crack lo these many decades, but finally mainstream economists were beginning to get a handle on it. Then, it would certainly be appropriate to give the Nobel to those researchers who had paved the way, if not for the solution then at least for the path to a solution. But is that really what’s happened in economic science?

Perhaps someone can come up with a mathematical model to predict the obfuscations and double-talk from economists when they finally begin to realize that their beloved paradigms are dying and, in fact, are the cause of most economic problems.

Thanks for the explanation of the prizewinners’ work. Boiling things down into a concrete example is a great way of making economics make sense, particularly to my way of understanding.

However, I think the analogy between this year’s winners and Obama’s peace prize is a bit overdrawn, and confuses the main point of the conclusion; do you mean to fault the prizewinners, or the mainstream of the profession here?

I still think Hayek’s Ricardo Effect offers the best explanation of why unemployment has lasted longer in the Fed meddling era. As Hayek points out in PII, stimuli from the state is spent on consumer goods. Keynesians think that will stimulate production, and it does for consumer goods. But the unemployment is mostly in capital goods, not consumer goods. And consumer goods makers handle the demand for more consumer goods by using labor more intensively, for example by having workers work overtime, instead of by purchasing labor-saving equipment which would stimulate demand in capital goods where the real unemployment is.

It’s still a problem of wages and not unemployment per se. Everybody can find a job quickly if they are willing to accept at whatever wages that are offered.

Well in Hayek’s description, job skills are specific and not easily transferred. In addition, producers need to see some kind of increase in demand for their products. Capital goods producers see demand from consumer goods producers. If they see no demand, they won’t hire someone because even if a workers agreed to work for free, the capital goods producer doesn’t need him.

Finally, Hayek wrote that modern jobs require capital. If the capital is destroyed in an artificial boom, those workers who depended upon it will not be able to find work until that capital is restored. For example, suppose I run a ditch digging company and my capital consists of 10 shovels operated by 10 workers. But one day a dozer rolls over 5 of those shovels and I don’t have the money to replace them. The five guys who ran those shovels will be useless to me no matter how low they go with their wages.

Capital destruction is a serious matter.

What about for a negative wage? Will your capital goods producer hire him for a negative wage?

All you’re doing is showing why the value of a person can decrease in value. It can decrease all the way to zero, and if that won’t do it, then he can work for a negative wage. Of course, he probably won’t but that just proves that involuntary employment is all about wages.

If a workers want to pay the employer for the privilege of working for him, then yes the employer will hire him. Barring that, employers need to invest a lot in new capital in order to create a job for new workers, no matter how low the wage. Without the capital for the worker to use, the worker is of no use. So the demand curve is kinked. Workers are worth nothing until the capital equipment has been purchased, then they are suddenly worth a lot.

I thought we were arguing about involuntary unemployment what what is its cause. Not about the value of the worker or what makes him more or less valuable.

Capital has to do with productivity but not employment per se.

Hayek says employment and capital are related. Few workers today can earn a living doing manual labor with no tools at all. For most jobs, workers need expensive tools. When those tools aren’t available, there is no demand for workers.

Robert, you are mistaken. The point of picking these and giving them the nobel memorial is not because of the current crisis. It has to do with the present government internal politics in Sweden.

They are on an all out war against the welfare system, removing and breaking it down and just got reelected.

Now their sights are on unemployment benefit and various home grown problems which are due to the heavy handed regulations governing hiring and firing.

In that context, it is of course fantastic to be able to lean back and say, “but hey even Nobel “prize” winners tell us we are right!”

What happened to your evisceration of Sumner?

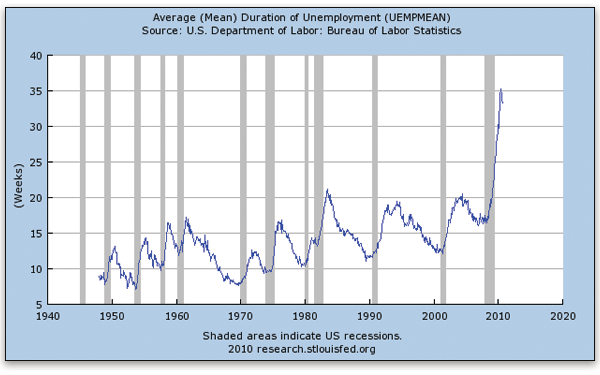

This may be a dumb question, but why does that chart show unemployment still rising after most of the “recessions” are over? Is a recession defined as certain time of slow GDP growth only, and employment takes awhile to recover after most recessions are over?

Yes, the NBER uses primarily gdp growth to determine the beginning and end of depressions, not unemployment.