CPI Officially Fell At 1.2% Annualized Rate in March (!)

Well hmm. If today’s CPI numbers had shown a positive (seasonally adjusted) growth rate, I was all set to trumpet from the mountaintops: “WAKE UP PEOPLE!! Bernanke et al. keep warning us of ‘deflationary’ pressures when there were three straight months of price hikes higher than the Fed’s alleged ‘comfort zone’ throughout the whole first quarter of 2009!!”

But alas, my case is now rendered dubious by the announcement that the (seasonally adjusted) CPI fell 0.1% from February to March.

OK look kids, yesterday I tried to do the honest thing by admitting that the falling PPI number was disconcerting, for those of you who share my estimate of my own economic acumen. So I hope you will not now roll your eyes when I question these BLS numbers.

First off, if you look at the actual BLS release (top row), you’ll see that the unadjusted CPI rose by 0.2%–an annualized rate of 2.4%–from February to March. OK? So the BLS’s “seasonal adjustment” took a 0.2% increase and transformed it into a 0.1% decrease. Notice that that’s a change of 150% downward from the raw number.

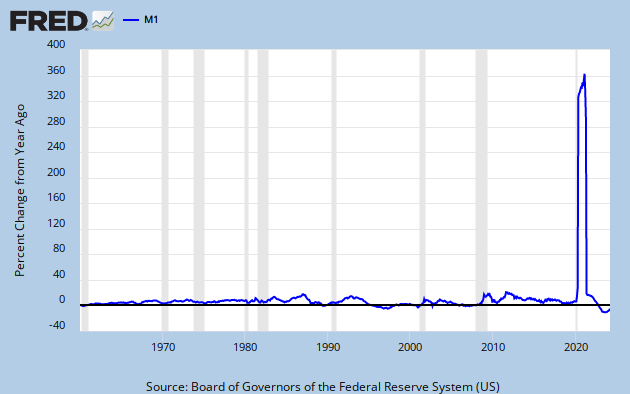

So you say, “Well, is that an unusual swing for the adjustments?” I don’t know, since I didn’t spend my childhood analyzing BLS releases. But for what it’s worth, if we go into the BLS archives for last month, we see that the unadjusted Jan-Feb increase in CPI was +0.5%, which the seasonal adjustment revised down to +0.4%–a downward revision of 20%. (Note that 20% << 150%.) Last point, and I realize this is anecdotal: Have you folks been grocery shopping lately? I am quite sure that the prices of just about everything are a lot higher now than they were a year ago. I had dabbled with the idea of looking into our Excel budgets for past months to compare grocery bills, but that would be useless since we used to shop more at Whole Foods (“Whole Paycheck”) and now we’ve worked Kroger more into the mix. =============== WHY I THINK LARGE PRICE INFLATION IS COMING Let me very briefly explain why all the people talking about “credit unwinding” etc.–and making comparisons to the Great Depression–are missing a big point. From 1929-1933, the quantity of money (let’s say M1) declined by about one-third. During 2008, M1 increased by 17%. OK, everyone got that? Not only did Bernanke prevent the quantity of money held by the public from falling, he boosted it at one of the highest annual rates in history. I’m not talking about bank reserves or the Fed’s balance sheet–which Bernanke of course has exploded–I’m talking about cash in circulation and checking account balances.

Capitalist Critics Called the Crisis

In a Slate article, Daniel Gross debates whether bankers or economists deserve more blame for the boom/bust. After saying that most economists missed the ball, he has a link to this sidebar in which he declares:

Among the economists who kept their heads during the boom and spoke sensibly throughout: Nouriel Roubini of New York University, Robert Schiller of Yale, Mark Zandi of Economy.com, and David Rosenberg, late of Merrill Lynch.

Argh. I’m not claiming conspiracy, but it’s still annoying that he only features Keynesians (right?) who were very pessimistic. What about Mark Thornton calling the housing bubble in June 2004?

Incidentally, did y’all know that Thornton was once a constable? You would know that and so much more lore if you went to Mises University just once. You might pick up some economics along the way, too, but that’s just icing on the cake.

I Didn’t Tell You So

OK folks, in the interest of getting to sleep at night, let me be honest and admit that I was very surprised at the reported outcomes of the captain being held hostage and also at today’s PPI report. Assuming the official accounts are accurate–i.e. that three snipers really all had head shots on a bobbing boat and acted just before the captain was possibly about to be gunned down with an AK-47, and that the BLS did not tinker with their “seasonal adjustments” to justify further Fed inflation–then my writings on these topics were off.

Specifically, if (say) snipers had missed and killed the captain, or if the PPI (and especially the forthcoming CPI) numbers showed 5% annualized price inflation rates, then I would basically have said, “You heard it here first.”

So there ya go.

Can You Have Inflation With Low Utilization?

For some time I have been meaning to complain about all the analysts–and not just talking heads on CNBC but even professional economists quoted in the WSJ–saying that, “The Fed’s worry right now isn’t inflationary pressures, because of the low capacity utilization rates.” In other words, they are saying that prices can’t possibly start rising until the real economy picks up steam.

But that’s the same Keynesian mistake that (I thought) was exploded with stagflation in the 1970s. Specifically, what happens is that a business will see its input prices rising, and so in reaction it ends up raising prices for its customers even though it may still be operating at less than full capacity. (Note I’m not giving a formal theory of how prices are set–obviously it is always about supply and demand–and I’m not really advancing a cost theory of price. I hope you get the short cut I’m taking here to get the point across.)

So it’s true, if my customers all of a sudden have more money (printed by the Fed) and the demand for my product starts rising, then I would respond by increasing output, i.e. capacity utilization would go up. But that will only be true in the initial stages of the inflationary “recovery.” Once that new money spills over into other sectors, you eventually end up with the same relative purchasing power of various people (generally speaking) and there is no reason for you to stay at the higher capacity.

Quick example: Disregarding the distributional issues etc., if the Fed doubles the amount of cash held by everyone, then prices roughly double. So if right now a businessman finds his profit-maximizing strategy–given current prices–is to run his factory at 40%, and to only carry half the employees he had during 2005, then why would a doubling of all prices lead him to change that? Yes yes, some businesses would, depending on their debt levels etc. But I hope it is now clicking with you that rising prices can occur amidst low capacity utilization (and high unemployment). Like I said, I thought we “learned” this lesson in the 1970s, except apparently for everyone quoted on CNBC or in the Wall Street Journal.

EPJ links to Stefan Karlsson making the same point:

…Zimbabwe has had extremely high money supply growth rate while also having extremely high unemployment (60 to 80%) and extremely low capacity utilization (20%). The result was an inflation rate of 231,000,000%.

My Qualified Defense of George Will’s Sea Ice Gaffe

In this MasterResource blog post I explain the controversy over George Will’s botched point about global sea ice area. I first point out that much of his error is due to the simple change in calendar year, rather than the passage of time (as his critics suggest), meaning that Will got unlucky. I then argue that in the grand scheme, it certainly is surprising–given all the media coverage of melting ice caps etc.–to learn that it is still quite common for global sea ice area to hit the same level as it had on the same calendar day in 1979. (In other words we’re not doing something dumb like comparing sea ice when the earth is far from the sun in 2009 with a period when the earth is closer in 1979. We’re doing the same day back in 1979 compared to today.)

Note that I am not taking a position in the post on whether Somali pirates are motivated by declining sea ice.

Chicago Economists Catching Up to the Austrians

On April 8 Casey Mulligan blogged about the perverse effects of the looming government bailout of those holding toxic–excuse me, legacy–assets:

Last fall the public learned that banks were not selling many of their legacy mortgages and mortgage-backed securities, despite the impression that ownership of the assets were hindering the banks’ lending. A variety of theories have been put forward to explain this failure, and to suggest what the government might do to fix it.

But the lack of trade in mortgage-backed securities may have something in common with the lack of trade in hybrid Chicago taxicabs. The secondary market for legacy mortgages may have stagnated largely because of the (ultimately correct) anticipation of a huge government subsidy. As I wrote last week, banks were not “unable” to sell their legacy mortgages; they were prudently unwilling to sell because they expected the government to eventually step in and help push the prices of the assets higher.

I’m going to go out on a limb and say that I offered this exact critique–namely that the government bailouts of insolvent investors was the primary cause of the “frozen” credit markets–more than a year before Mulligan. However, I am too lazy to go look it up.

******

I guess to be safe, we should do this: If you think you’ve found a contender, then first email it to me and then post it in the comments. I’m just trying to avoid a possible problem where some guy posts the winning entry, and then different people try to tell me that they are “Brian Smith” (or whatever) and give me different mailing addresses. (I know I know, the prize has to actually be valuable to make cheating worthwhile.)

I am the final decider on the winning entry.

Last thing: I have considered the possible embarrassment of announcing this contest and then nobody responds. I reserve the right to post answers under assumed names to avoid humiliation in that event.

A Man a Plan No Bank Panama

(For those perplexed by the title, I am alluding to the coolest palindrome ever.) I met this guy at my talk in Boston to Suffolk Law students. He told me that Panama had no central bank, and its macroeconomic performance has been just fine, thank you very much. In fact the Panamanian constitution says:

“There will be no forced fiat paper currency in the Republic. Thus, any individual can reject any note that he may deem untrustworthy.”

I Tell the Indians to Adopt a Gold Standard

I am quoted in this Times of India piece on the gold standard:

Robert Murphy, Adjunct Scholar at the Ludwig von Mises Institute in Alabama, USA, says, “A gold standard is essential today because it would force central banks to raise interest rates to their correct levels. In fact, it would work as a very good safety precaution, since it places a firm limit on how much inflation the central bank can create. Also, it’s an excellent option for emerging economies like India, since any country with 100% gold backing for its currency would see its own currency appreciating against others, and more capital would begin flowing there”.

Recent Comments