What Will It Take to End the Recession?

Mario Rizzo has (as usual) an interesting post over at ThinkMarkets on the possible end of the present recession. I personally am withholding judgment on whether the “recession is over,” as many analysts seem to think. But even if, years from now, the NBER finally decides that yep, the recession lasted from Dec 2007 to May 2009, then I still won’t say, “Good thing we had Bernanke at the helm!” As I commented after Mario’s post:

What is interesting of course is that every recession in history has always ended. So it is odd when people want to find “the cause” for the recovery this time. (I realize you are aware of this, Mario; I’m just elaborating on your post.)

For example, suppose everybody ends up thinking it was TALF. Well, there was no TALF during the last x recessions (I don’t know how many there were in between the Great Depression and now).

I keep coming back to medical analogies. If a kid gets the flu, and each of his five brothers tries a different remedy–like kicking him in the face, pouring syrup on his toes, and reciting limericks–the kid would eventually get better. Some of his siblings’ remedies did nothing, and some actively prolonged the sickness.

Yet after he eventually gets better, the siblings would argue over whose cure “worked.”

USPS Forever Stamps as Inflation Hedge?

I’m going to be at the Mises Circle in Dallas (or is it Fort Worth?) this weekend, so blogging may be sparse. In the meantime, can somebody convince me why I shouldn’t buy $1000 worth of “Forever” stamps from the Post Office?

Absolute worst scenario, Krugman is right–and yes, that would be the worst scenario for me–and we are stuck in Japan mode for a decade. OK no big whoop, I never have to buy stamps during that period. Sure I would regret having sunk so much cash into that many stamps, but if it comes down to it, I could sell them to my neighbors and friends at a slightly reduced price (after explaining my foolishness). You might ask, “How many letters do you plan on mailing?!” but I think I could slap a bunch of them on regular packages too. So instead of paying $4.95 for them to ship a book the next time someone wins a , I can instead buy my own generic envelope and slap a bunch of stamps on it, right?

On the other hand, suppose my predictions about massive price inflation come true. Then I’m sitting pretty because (a) I have completely hedged one of my recurring business expenses and (b) Paul Krugman would have been ridiculously wrong. Those two together might make $8 milk (which you need to buy online because of the price controls) almost tolerable.

The only major flaw I see in this is the possibility that the Post Office doesn’t honor pre-2010 Forever stamps at par, because “obviously we need to adjust for the 20% inflation that kicked in.” So if we really did get hit with heavy inflation, I might start unloading my Forever stamps (to neighbors etc.) at a nice discount from their point of view, so I lock in most of my gain before the Post Office debases them.

The Connection Between Government Debt and Price Inflation

Back when I was a college professor, I would always drill home to my students that government budget deficits didn’t cause (price) inflation per se. For example, if the country were on a gold standard with 100% reserves in the banking system, then the total quantity of money wouldn’t have anything to do with how much the government borrows, just like it isn’t affected by how much Microsoft borrows in a given year.

However, in the real world the layman’s suspicion is justified. In our wacky system, the Federal Reserve ultimately is responsible for the CPI, in the sense that the Fed exercises a huge influence over the ultimate money supply. But if the government is running massive deficits year after year, this puts tremendous pressure on the Fed to inflate, because it (a) keeps interest rates down, making it cheaper to borrow and (b) reduces the real burden of previously accumulated debt.

But before today, I had never realized just how related the federal debt was to the general purchasing power of the dollar. Tom Singleton emailed me a chart from CaseyResearch, the gist of which I reproduce below using FRED:

In retrospect, I suppose you could argue the causality is the other way around: The Fed inflates for some other reason, which raises prices, which makes the government’s appetite for (nominal) debt go up. The chart above wouldn’t settle the direction (if any!) of causation. But I think the old-time wisdom is right: When the government runs massive deficits (and surely $1.8 trillion qualifies), just wait for the dollar to plunge.

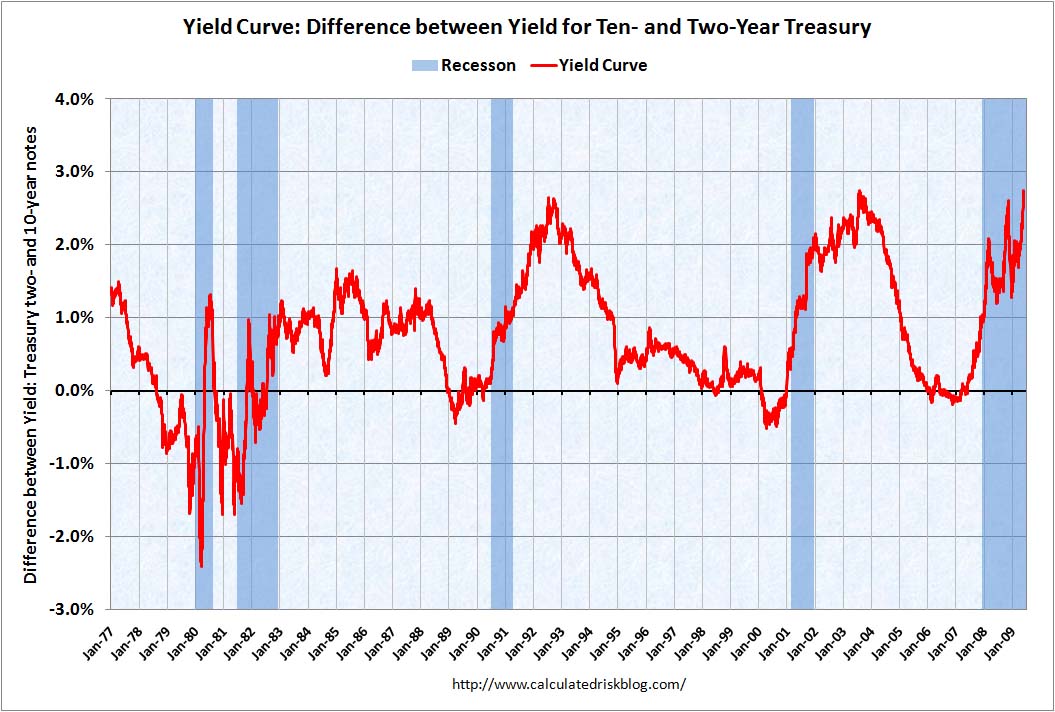

Slope of Yield Curve at Record High

The econogeek blogosphere is abuzz because the slope of the yield curve is at a record high. Here’s the chart from Calculated Risk (HT2 Greg Mankiw):

Whenever I see a chart of a spread, especially when it’s over a long time frame, I like to see its constituents:

The yield curve holds a revered place in the hearts of many, because it is surprisingly good in forecasting recessions (when it “inverts,” meaning when interest rates of shorter maturity rise above interest rates of longer maturity). Notice in the first graph above, that the spread goes negative before each recession. And contrary to an old joke about predicting 8 of the last 3 recessions (or whatever), I’m pretty sure the inverted yield curve is never, or at least rarely, wrong, going back to the 1960s.

When I worked in the financial sector my firm did a research paper on this, and I remember thinking that the academic literature didn’t really have a good explanation for this amazing phenomenon. I think the Austrian theory of the business cycle can explain it: The Fed pushes down short rates by inflating the credit markets, and so you get a few years of a boom. But then the Fed gets scared and hikes short rates back up, and you get a recession.

(And it’s not really that hiking up short rates “causes a recession.” More precisely, when the Fed stumps pumping in funny money, short rates rise and the economy is allowed to cleanse itself of the malinvestments made during the unsustainable boom, a cleansing process that is unfortunately painful and requires workers to change jobs.)

This was actually the topic of Paul Cwik’s dissertation [.pdf]. It’s been years since I read it, and I honestly can’t remember whether I thought he hit it out of the park; he criticized me in a few footnotes and I think I sulked over that instead of his main points.

In our present environment, of course, I think the reason short rates are staying low, while ten-year yields are rising, is that the Fed is still very loose while long-term deficits are making investors worried.

Krugman Contradicts Krugman on California

Earlier this week Paul Krugman’s NYT column discussed the sorry state of California finances. According to Krugman, the reason the Golden State is in such a hole these last few years, is because of a tax revolt in 1978:

The seeds of California’s current crisis were planted more than 30 years ago, when voters overwhelmingly passed Proposition 13, a ballot measure that placed the state’s budget in a straitjacket. Property tax rates were capped, and homeowners were shielded from increases in their tax assessments even as the value of their homes rose.

The result was a tax system that is both inequitable and unstable. It’s inequitable because older homeowners often pay far less property tax than their younger neighbors. It’s unstable because limits on property taxation have forced California to rely more heavily than other states on income taxes, which fall steeply during recessions.

For those who don’t know about it, Prop. 13 was awesome. (I am well aware of its details because of my time spent working for Arthur Laffer, who at the time was one of its biggest proponents.) By limiting real estate taxes to 1 percent of the assessed value, it overnight cut property taxes by more than half. (!) The ballot initiative’s authors were also smart to add in a provision that the assessed value could rise at most by 2 percent per year, unless there were a transfer of ownership. So for people who stayed in their homes, the most their property taxes could rise was 2 percent a year.

In addition, Prop. 13 required that both houses of the state legislature had to get a two-thirds vote in order to pass any further tax hikes. You wouldn’t expect something like this to come out of California, now would you? (But then again Ronald Reagan came out of there during the same period.)

OK so now you can see what Krugman is talking about in the block quotation above. But still, what does that have to do with the current crisis? How does California’s 11-percent unemployment rate (cited by Krugman early in the article) relate to Prop. 13?

Even more important, however, Proposition 13 made it extremely hard to raise taxes, even in emergencies: no state tax rate may be increased without a two-thirds majority in both houses of the State Legislature. And this provision has interacted disastrously with state political trends.

Isn’t that funny? California’s economy is in the toilet because its taxes are too low? For what it’s worth, the Tax Foundation says that in 2008, California’s state and local “burden of taxation” was 6th highest in the nation. (That’s somewhat near California’s 5th highest unemployment rate; an interesting coincidence.)

But don’t worry, the rest of us are safe from California’s irrational aversion to taxes:

Will the same thing happen to the nation as a whole?

Last week Bill Gross of Pimco, the giant bond fund, warned that the U.S. government may lose its AAA debt rating in a few years, thanks to the trillions it’s spending to rescue the economy and the banks. Is that a real possibility?

Well, in a rational world Mr. Gross’s warning would make no sense. America’s projected deficits may sound large, yet it would take only a modest tax increase to cover the expected rise in interest payments — and right now American taxes are well below those in most other wealthy countries. The fiscal consequences of the current crisis, in other words, should be manageable.

But that presumes that we’ll be able, as a political matter, to act responsibly. The example of California shows that this is by no means guaranteed….

So will America follow California into ungovernability? Well, California has some special weaknesses that aren’t shared by the federal government. In particular, tax increases at the federal level don’t require a two-thirds majority, and can in some cases bypass the filibuster. So acting responsibly should be easier in Washington than in Sacramento.

Now wait just a second. It sure sounds like Krugman is saying California should raise taxes now, in order to reduce its budget deficit. (Doesn’t that sound like what he’s saying?)

But in his December 2008 NYT article, Krugman warned the state governors not to worry about reducing their deficits, since that’s what Herbert Hoover foolishly did in 1932.

OK OK, maybe Krugman would clarify and say that California is in danger of scaring away potential bondholders, and so it needs to raise taxes not to entirely close the deficit, but just to keep people willing to lend to it.

But no, that doesn’t really work either, because in this blog post earlier this month, Krugman explained that if the Chinese decided to stop buying so much Treasury debt (thereby driving up interest rates), that would actually boost the American economy. So if people who lived outside California stopped lending them money (even though the Golden State–heh heh–has a constitutional requirement for a balanced budget), that should boost gross state product, right? (The specific mechanism in the China example was that it would weaken the dollar and thus boost exports. Can anyone translate that into a case where different regions use the same currency? I mean, the choice of currency shouldn’t affect the trade flows, right? But then again I am constantly mystified by the results of a Keynesian model.)

The more I try to reconcile these three writings by Krugman, the more I think that he just grabs whatever argument he needs at the time, in order to justify bigger government and redistributionism. I know that sounds petty to say, but really, that’s the one common link in just about everything Krugman writes. As Scott Sumner put it recently:

Over the last few months I have had a chance to closely examine many of Krugman’s recent and past writings on fiscal and monetary policy. One thing that I notice is that Krugman is very skilled at making an argument. He can use the same basic model to make either monetary or fiscal policy seem like the only reasonable option. All that is required is that one tweak the assumptions in such a way that the less favored policy seems either undesirable or infeasible.

Cost/Benefit of Waxman-Markey: It’s Not Pretty

I actually spent a good portion of my holiday weekend researching for / writing this MasterResource post on Waxman-Markey. A juicy part:

Now we see the weakness in [relying on the “social cost of carbon”], when trying to assess the net benefits of unilateral climate policy. Once we take leakage into account, we see that the standard measure of SCC overstates (possibly grossly so) the true costs to society from an additional unit of emissions. In reality, there are two things going on: When a U.S. manufacturer produces more units of a carbon-intensive good, it is true that he emits more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This is what the SCC looks at, and judges him accordingly.

However, the U.S. manufacturer also pushes down the world price of the good in question, and that tends to cause other producers to emit less CO2. Thus, there is a positive externality laid on top of the negative externality. The greater the scope for leakage, the greater the positive externality. In the extreme, where U.S. operations would be completely outsourced to China (in terms of carbon emissions, if not output of final goods), then the correctly measured “social cost of carbon” for U.S. operations would be zero, in the context of a unilateral U.S. cap.

And the takehome messages:

(A) If the U.S. implements Waxman-Markey unilaterally, the environmental benefits will be even less than indicated by Chip Knappenberger’s pessimistic analysis.

(B) If the whole world implements Waxman-Markey, then the loss to economic output will far exceed the reduction in expected environmental damages.

Samwick’s Juvenile Argument Against the Tea Parties

Editor’s Note: In a recent post I summoned the Thundercats and they responded as usual. This post relies on their sleuthing. I’d also like to thank YouTube.–RPM

Andrew Samwick (HT2 Brad DeLong) couldn’t take it anymore when the Cato Institute’s David Boaz referred to this year’s “Tea Parties” as the “revival of a freedom movement.” Writes Samwick:

At moments like this, we go back to Milton Friedman’s adage, “To spend is to tax.” I cannot really come up with a better word than juvenile for the tea parties — don’t protest the taxes unless you can identify the specific cuts in expenditures that you would make to bring the budget into balance. If you think taxes are bad, then you should think deficits are worse, because they raise the taxes of people who were not represented in the decisions to spend the money.

That’s the real lesson from the Revolutionary War period that should be drawn. And the danger for the Libertarians is that if they don’t put the reduction in expenditures ahead of the reduction in taxes on their agenda, they are destined for another abusive relationship down the road.

Before I proceed to annihilate Samwick, let me offer one caveat: I agree that there probably wouldn’t have been these protests had McCain won. It’s not because the average Tea Party protester is really a closet racist, a la Janeane Garafola, but rather that I think right-wing radio, Fox News, etc. might not have stoked the flames if their guy won. But I could be wrong.

In any event, what is unambiguous is that the Tea Party-goers were protesting spending. And we don’t need to dig up obscure footage from a rally in Montana to make the point; we need only examine the most infamous of all reporting on that day (albeit not the most famous portion). Start the below at 2:30, and just give it 60 seconds. Does that lady sound like a Republican ideologue who loves big spending and low marginal tax rates?

Bob Roddis captured the below stills from other interviews that this same notorious CNN reporter conducted; check out the signs. (And note that the guy who was the subject of her most famous interview has a sign behind him too, which seems just as cognizant of the connection between current spending and future tax burdens on current non-voters.)

Beyond the above evidence, is the simple fact that the original motivation for the Tea Parties was Rick Santelli’s rant. And remember, that rant had nothing to do with marginal tax rates, it had to do with the government spending money bailing out people who were behind on their mortgages.

What do you think, Mr. Samwick? Do you have something you’d like to say to the rest of the class?

Oil Prices Are Rigged? It Just Ain’t So!

I explain in the latest Freeman. Excerpt:

Even though oil prices have fallen and quieted the price-conspiracy mongers, you can bet that when prices go up again, they will be back in force. It happened last time. For example, in an article for Time last August, Ari Officer and Garrett Hayes ask, “Are Oil Prices Rigged?”. Our cynical authors—who are Stanford graduate students in financial mathematics and materials science/engineering respectively—answer in the affirmative, but their arguments are shockingly ignorant of how markets work.

(I wrote the response shortly after their article first ran last August, but for various reasons it kept getting pushed back until the present issue.) As if to prove the point, I coincidentally was just reading an article a colleague sent me concerning the latest charges of evil oil speculation.

Recent Comments