Murphy Takes on Another (Post) Keynesian

Remember when Galvatron says, “First [Optimus] Prime, then Ultra Magnus. And now, you. It’s a pity you Autobots die so easily, or I might have a sense of satisfaction now!” ? Yeah, I thought that was pretty sweet too.

Anyway, I recently took on Dean Baker after our Congressional showdown. Then in the most recent American Conservative, I respond to the article by James Galbraith in the same issue.

Can Krugman be far behind?

Yet Another Stunning Empirical Refutation of Keynesianism?

If I had to summarize in five words my critique of Keynesianism, it would be, “Spending doesn’t create real income.” (Then, after the standing ovation, if people wanted an encore, I would say, “Production does.”)

I admit I just glanced at it, but I do believe Daniel Kuehn unwittingly provided empirical confirmation on his blog. (Check my comments.)

Rorschach on Economics

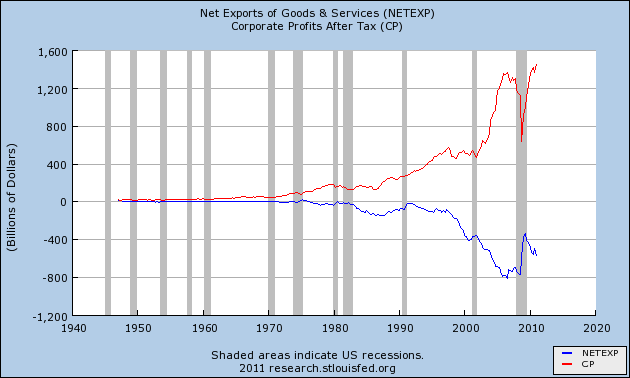

Someone (sorry I’ve forgotten who it was) emailed to get my reaction to this chart posted on Zero Hedge:

The obvious “fight the power” reaction to the above is to say, “Those traitorous One World banksters! They outsource manufacturing jobs in order to fatten their own bottom line.”

But that’s not necessarily what’s going on. Since 1991, I would say what’s happening is that we’re seeing two big boom periods–during which the trade deficit went up, as well as corporate profits–that then collapsed and reversed the patterns. (Notice how the lines move when they cross the gray recession bars.)

Keep in mind that a current account deficit (which is a broader notion than trade deficit, but you can use the terms interchangeably for our purposes) is the flip-side of a capital account surplus. So if the Fed fuels an artificial boom, such that assets prices in the US are rising, then foreigners want to get a piece of the action. On net they want to buy more US assets, than Americans want to buy of foreign assets. The only way that is possible is if the US runs a current account deficit. Intuitively, as US stocks, real estate, etc. are booming in market value, Americans are willing to sell off more of them (in absolute dollars) and use the proceeds to import more TVs, cars, and other goodies from foreigners as payment.

Nick Rowe on Forecasting Price Inflation

[2nd UPDATE in text.]

[UPDATE below.]

Nick Rowe has an intriguing post that pushed me over the edge to mention something that’s been bothering me for a few weeks now. (No, I’m not talking about the rash.) Here’s Rowe:

You can’t test whether core inflation is a useful indicator for a central bank to look at just by seeing whether core inflation forecasts future total inflation (or whatever the bank is targeting). You can’t test whether anything is a useful indicator for central banks to look at that way. Everything ought to look useless by that test, if the bank is doing it right. What you are testing is whether the bank is doing it right.

If a central bank is targeting (say) 2% total inflation at a (say) 2-year horizon, and if it’s doing it right, then deviations of total inflation from 2% ought to be uncorrelated with anything that the bank knew 2 years ago. This means that nothing (i.e. nothing in the bank’s information set) should forecast 2-year ahead total inflation, if the bank is reacting correctly to those indicators. Core should fail to forecast future total inflation. Total inflation should fail to forecast future total inflation. Trimmed mean inflation should fail to forecast future total inflation. Unemployment should fail to forecast future inflation. Everything should fail to forecast future total inflation.

This is an immediate implication of rational expectations (on the part of the central bank). The bank sets monetary policy, looking at the indicators in its information set, so that the bank’s forecast of 2-year ahead total inflation is equal to the 2% target. Deviations of actual inflation from 2% are therefore forecast errors. Under rational expectations (on the part of the bank) forecast errors should be unforecastable from anything in the bank’s information set. They wouldn’t be rational if you could forecast errors.

When you look at correlations between core inflation and future total inflation, you are not testing whether core inflation is a useful indicator of future headline inflation that the bank should pay attention to. You are doing something quite different.

Now I’m not fully on-board with the rational expectations stuff, but Rowe’s basic point is totally right. (In the comments, he’s goes toe-to-toe with some critics and neither side is bluffing. So if you want to get your econometrics game on with a debate involving terms like “orthogonal” and “serial correlation” then jump right in.)

In the context of my favorite living economist, Krugman has repeatedly been mocking people who want the Fed to tighten, by showing charts of core inflation versus headline inflation. Krugman’s point is that in the past, just because headline inflation rose by (say) 4 percent in a 12-month period, while core only rose by (say) 2 percent, that wouldn’t lead us to think headline inflation would be unusually high in the near future. In other words, Krugman was saying that core inflation seemed to predict headline inflation better than headline inflation predicted itself. Ergo, Krugman concludes, people who are freaking out right now about headline inflation–driven by rising commodity prices–are looking at a bad indicator. Instead they should look at core CPI, which is still rising at a reasonable pace.

Yet this proves nothing, for the reasons Rowe gives. What if the Fed in the past jacked up rates whenever headline inflation started to pick up, in order to maintain the target of stable core inflation?! Then history would look just like what Krugman is now pointing to, as proof that the Fed should ignore headline inflation. Except, this time, if the Fed ignores the strategy that (in principle) it may have been following to generate the charts up till today, we will now see a breakdown of the pattern.

Note that my story isn’t necessarily what’s going on; maybe Krugman’s version is right, and the Fed has always been (correctly) ignoring headline inflation and looked at core CPI for the last 30 years. My point is simply that Krugman thinks he is demonstrating his interpretation by pointing at charts of core versus headline inflation rates, and that by itself tells us just about nothing.

For example, back in the early 1980s Arthur Laffer met with Paul Volcker, who apparently literally pointed to a chart of a commodity index, and told Laffer that when commodity prices went above a certain range, Volcker would tighten. When they dropped below a certain point, he would loosen. That led Laffer to write a WSJ piece at the time, titled something like, “Does Volcker Have a Commodity-Price Rule?” (I can’t find it on google, but I saw it with my own eyes and heard Laffer tell the story several times. UPDATE: Aristos sends me an excerpt from Laffer’s book, talking about this episode.)

So assuming that anecdote is true, and Volcker really were explicitly following a commodity price rule, Krugman’s method would lead you to conclude that commodity prices had little to do with future CPI. I mean, every time commodity prices shot up, they would soon come back down, and next year’s CPI wouldn’t be much above the prior year’s. So today, if commodity prices shoot up, the Fed can safely ignore it and keep monetary policy nice and loose, since “history shows” that commodity prices are just wacky and volatile, they’ll come down on their own. CPI has little to do with commodity price spikes, right…?

I’m trying to think of an analogy to do this justice. Maybe something like: “We don’t need to turn on the air conditioner this summer even when the temperature goes up outside. We looked at a history of outside versus inside temperatures over the last 20 years, and there’s surprisingly little correlation between the two. So let’s save a bunch of money this year by turning off the AC and heat.”

UPDATE: In the comments, “NickRoweFan” points us to an earlier Rowe post that spells out the thermostat analogy much better than I did.

Who Needs Advertising?

I am sure there are nuanced arguments for government intervention in the health care sector. Not that I would endorse them, but I’m sure they exist. However, Krugman approvingly quotes the following today on his blog, and I don’t think it qualifies:

A medical technology company is going public to generate the money it needs to advertise its products to hospital directors and insurance-company reimbursement officers. This entails significant extra expenditures for marketing, the new stocks issued to fund the marketing will ultimately have to pay dividends, banks will have to be paid to supervise the IPO that was needed to generate the funds to finance the marketing campaign (presumably charging the industry-cartel standard 7%)…and all this will have to be paid for by driving up the price the company charges to deliver its technologies. But beyond the added expense, why would anyone think that a system in which marketing plays such a large role is likely to be more effective, to lead to better treatment, than the kind of process of expert review that governs grant awards at NIH or publishing decisions at peer-reviewed journals? Why do we think that a system in which ads for Claritin are all over the subways will generate better overall health results than one where a national review board determines whether Claritin delivers treatment outcomes for some populations sufficiently superior to justify its added expense over similar generics?

So why stop there, Krugman? (To repeat, those aren’t Krugman’s words above, but he approvingly quotes them.) Why not have a single payer for sneakers and alcohol? Can you imagine how much more efficient these industries would be?

Also, for people like Daniel Kuehn who can’t understand why I exclude Krugman from the ranks of “free market economists”–look at the bold above. If “free market economist” includes people who believe that, then the term is meaningless.

Police Don’t Want You Filming Them Filling a Car With Bullets

I have no idea what the context is for the initial shooting, but Tony sends along this story:

After a horrific shootout on the streets of Miami, Narces Benoit and his girlfriend witnessed the finale: police firing a barrage of rounds into a man’s car. Narces recorded it. The police smashed his phone. But first? Hidden SD card.

The horrendous sidewalk firefights took place over Memorial Day, leaving officers and pedestrians alike injured. Narces had an HTC EVO with him, the Miami Herald reports, which he used to film police killing a suspect in his car, after which he says cops pulled guns on him for recording the incident. The video cuts off before the rest of his allegations—that he and his girlfriend were thrown out of their car, and his phone smashed on the street—but everything leading up to that point was saved by some fast thinking. With guns in his face, Narces quickly popped out his phone’s SD card and stuck it in his mouth. With the card intact, the chaotic video above is now spreading across the internet.

I realize this is no matter to joke about, but the opening of this video kept making me chuckle. Apparently Narces is a coroner. (You’ll see what I mean.)

Murphy on FreedomWatch

I toyed with the idea of telling the Judge that actually, they jacked up income tax rates to ridiculous levels pretty soon after they were implemented–the top rate was 77% in 1918–but I wasn’t sure how to get the proper tone across so I played it safe.

Republicans Flirt With Technical Default

This surprises me. Some Republicans are openly talking about missing a few interest payments, if it would get the Democrats to agree to bigger spending cuts. Fortunately David Frum is there to wag his finger at the children.

I don’t understand why the younger Republicans don’t start demanding widespread asset sales. I would think that would sell politically a lot better than actually missing payments to bondholders. I suppose it might be hard to say you want to dump hundreds of billions worth of student loans, since that would presumably make it harder for the next crop of kids to bury themselves in debt. (Go figure.) But I would think selling off real estate, or expediting drilling rights, would be no-brainers.

Recent Comments