My Final Word (This Generation): The DEBT Really Is Fundamental

If you have begun skipping these, I ask you to read this final word from me. This is new stuff.–RPM

OK kids don’t worry, this is going to be out of my system now, unless Krugman or somebody puts up something new. But I really wanted to illustrate the epiphany I had last Friday, which caused my acid-trip post. Before that post, I had settled this for myself, by thinking that it wasn’t really the debt per se that burdened future generations, but instead was the taxes levied on them.

But now I disagree with that. Yes, the taxes on them are a burden, but if you want to avoid paying down the debt, then you are forced to pay higher interest on the debt. (In other words, if you are taxing future generations more than they are earning in interest on the debt they’re carrying, then you pay down the debt.) So the problem is, to make the lending to the government voluntary, you have to basically subsidize the lenders. Thus, if you are in a steady state where the level of the debt stays constant–where the government just keeps paying the interest each period–then the losses to people in the form of debt service payments are counterbalanced by the gains to the bondholders. (This is what made me think I was turning MMT.)

So now I’ve come full circle, and think it is more accurate to say that it is the debt per se that burdens future generations. In the act of running up a debt, the present generations gain not only in utility, but they physically consume more apples. And then, if descendants want to pay down the debt (not just roll it over), they not only lose in utility terms, but they literally put fewer physical apples in their bellies.

When I was puzzling over this outcome, something obvious occurred to me: What does it mean in financial, balance sheet terms to run up the government debt? I don’t even care what is done with the funds. Just focus on the act of the government printing up an IOU for, say, $10,000, and giving it to somebody who is alive today. What just happened, in financial accounting terms? Why, the recipient of that new bond gained an asset with a market value of $10,000. So somebody else must have lost. Who? The government, sure, but more strictly speaking it is the future taxpayers. The government, by running up a debt today, is effectively giving out claims on the income of future taxpayers. So I think that is fundamentally imposing a burden on them, just as surely as a family that goes out to dinner and puts it on the credit card, has surely benefited itself in the present by imposing a burden on itself in the future. Sure, when the bill comes due, the family can default, and at that moment transfer the burden to the credit card company. But nobody in real life would deny that at the moment of running up its credit card bill, the family has imposed a burden on its future self.

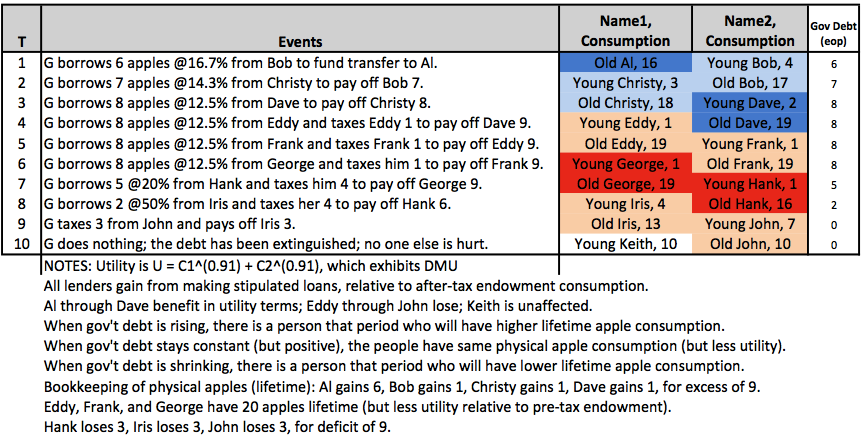

Without further ado, here’s an illustration of the above principles. I am pretty sure everything checks out internally. The only oddity is that the interest rate goes down with a higher volume of borrowing, but that’s just because I wanted an easy pattern in the debt movements and consumption patterns. Every lender gains from making the loans.

BTW, Nick Rowe is still my hero. I don’t think he ever had a misstep in this entire debate. Even on this issue of what happens if society just carries a positive government debt for a few generations, Nick instantly told me (paraphrasing), “They have the same lifetime consumption but their utility is lower. So they’re still hurt in the economically important sense.” But I needed to see it with my own eyes to “get” it…

Last thing: I’m not going to bother doing an illustration, but once you get the above, tweak the model so that some periods have really high apple crops, and other periods have awful harvests. So in principle apples from good years can be “moved” to apples in bad years. But there is a physical constraint on how much “time-shifting” can be done, because of the lack of a time machine. When you start thinking of it like this, the moralist’s worries about “not burdening the future with our debt” and the presumption in favor of “paying down debts in good years” is crystal clear. In contrast, if Krugman or Abba Lerner were advising the people in this world, during the good years they would tell them to not bother paying down the debt, since that couldn’t possibly help future generations on net.

Hate to add this tangent at this stage, but doesn’t government debt issuance incur unique transactions costs of its own, which reduces output, and thus reduces long term productivity to the extent productivity depends on prior output, and thus we can say debt burdens future generations with lower wealth than they otherwise could have had if those unique transactions costs did not exist?

I don’t think one can plausibly abstract away from this cost of debt (imagine there having to be more government agents doing the logistics of debt issuance, and more resources like computers and whatnot going to that debt issuance, rather than private productive use).

Is this not an example of a “the burden is the debt per se“?

M_F: Yes. The biggest such cost would be the distortionary effects of future taxation. (Those are assumed away in Bob’s and my examples, by assuming lump sum taxes with no collection costs). But since the other side (Paul Krugman for example) recognise those costs, that’s not really at issue.

Actually, I was thinking my example abstracts away from taxation. Suppose that the entire government’s budget is, for a finite period of time, financed entirely by borrowing and rolling over the debt every year.

I am talking about the inevitable costs of debt design, issuance, logistics, and so on. The resources and labor required to engage in this activity.

Does the other side recognize these costs? If not, then aren’t these costs (which are necessarily associated with debt issuance) a burden on the future, which means debt per se burdens the future (since it is impossible to issue debt cost free, i.e. resource and labor free)?

Take the extreme case. Suppose 100 million people in the country are, for the next year, going to engage in a massive government debt issuance program. The entire thing is financed by borrowing, which will be rolled over for a few generations.

With that many people engaged in this activity, instead of replacing worn out and used up capital, are we not going to leave future generations with less wealth than they otherwise could have had if those 100 million instead stayed in the factories, farms, and offices?

Is government debt issuance not akin to the entire country engaging in a massive drinking binge, letting the country’s capital infrastructure crumble and rot, which leaves our descendants with an economy that looks like it has been subjected to a bombing raid?

Which sort of leads to another question…are we morally obligated to refrain from consuming the entire country’s capital, for the sake of future generations, say 100 years from now?

If you say yes, why?

If you say no, then, if you’ll excuse me if you’ll pardon me, isn’t this whole OLG model an exercise in vanity and empty boasting?

I am being serious here. I think you and Murphy have shown that government debt can burden future individuals. Now that we have the technicals, what about the ethics?

(Future individuals meaning ALL individuals past a certain point in time)

“Hate to add this tangent at this stage, but doesn’t government debt issuance incur unique transactions costs of its own…”

As does government taxation now. If we are talking ceteris paribus (government spending is identical, we’re just asking how to fund it), then so what? Why in the world should we suspect that debt issuance has *higher* transaction costs than taxation, especially considering the byzantine tax code we have at present?

I am not talking ceteris paribus in terms of spending. After all, considering how deficit financed spending is “easier” to implement than taxation financed spending, it can be argued that deficit financed spending would tend to increase overall spending, ceteris paribus.

Be that as it may, I never said anything about whether debt has higher or lower transactions costs than taxes. My point is whether debt per se has transactions costs and hence burdens on future generations. If it does, as you seem to admit, then you should accept the argument that debt per se burdens future generations, that there are “analytic” costs, as it were, associated with debt.

I already mentioned the following in another post to you, but you seem not to have read it, or if you did, you didn’t accept the principle of the argument, so I will say it again: it is no argument against the claim that debt per se burdens future generations in the way I am describing here, by saying that since some other action (i.e. taxation) also has transactions costs, that somehow I am not entitled to argue that debt per se burdens future generations APART from taxation and redistribution issues.

if you want to avoid paying down the debt, then you are forced to pay higher interest on the debt.

How does this explain the negative real rates we’ve seen recently? (If in fact that’s what we’ve seen, perhaps I’m mistaken.)

Front running the Fed.

Anon I’m not talking about interest rates. I’m talking about the volume of interest payments relative to the amount people are taxed. Since there are no other gov’t expenditures in my model (after period 1) except debt service, I’m making the basic point that if the government taxes people $X in some period, and the interest on the gov’t debt in that period is $Y, then if X>Y the debt has to go down. So if you want the debt to stay the same, you can’t tax people more than the interest payment due to bondholders.

Why, the recipient of that new bond gained an asset with a market value of $10,000. So somebody else must have lost. Who? The government, sure, but more strictly speaking it is the future taxpayers.

The problem with this reasoning is that the recipient of the bond is also a future taxpayer.

It’s not a problem actually. Your argument doesn’t mean the taxes and interest payments necessarily balance out for the recipient of the bond. In fact, it is almost a certainty that it won’t balance out, since taxes are spread over 150 million people, whereas a bond goes to one person.

Note, that I’m not saying it *will* wash or balance out in practice, only that it *can* in principle.

But this applies the intra-generational debt as well. Not all of the old people will own bonds either.

OK, in principle, sure, but are you sure that this really represents a “problem” for the statement that you responded to above?

In order for it to work, the taxes on bondholders must exactly match their interest payments from the bonds. That would require the state to ONLY tax bondholders (since money is fungible).

For the statement you responded to above, if the caveat “assuming an absence of perfect taxation-interest balance”, would you agree with it? Did it really have to have that caveat now that it has been re-examined?

Right, anon. That will be a wash in the future, clearly.

The problem with this reasoning is that the recipient of the bond is also a future taxpayer.

You and Gene really don’t see the important point about the future recipient (possibly) having to restrict his consumption in order to “inherit” the bond?

This is why Krugman’s posts throughout this debate have been missing the essential Rowian point, which only the OLG model can bring out: Krugman keeps using thought experiments where the government hands out for free bonds to one group of people. Then he thinks, “Duh, taxing some people to pay off the other people, is just a wash.” By the same token, if we suddenly learn that the president in 2016 will issue bonds de novo to some people, then it is a wash among that time period.

But things are much different when the way you get your hands on the bonds, is through reducing your consumption earlier in your life. Even if every single American in the year 2100 holds an identical amount of bonds, so that the government takes $x,000 from each person and then hands that money right back, it’s not a “wash” in a very important sense. Those people might have had much lower lifetime consumption and utility because of the debt the government decided to pay down on their backsides.

“But nobody in real life would deny that at the moment of running up its credit card bill, the family has imposed a burden on its future self.”

Right. And nobody in this debate DOES deny this! What the “other side” says is that is exactly offset by funds flowing to future bondholders. The difference is this: in your credit card example, the family only has the obligation to pay. Someone else has the right to the stream of payments. With domestically held debt, BOTH the people with an obligation to pay AND the pay with the right to the stream of payments are in the future generations we are examining.

This “insight” you are having above actually makes me think you’ve have never really gotten the argument of Lerner et al in the first place, rather than that you have gotten it and now transcended it.

Right. And nobody in this debate DOES deny this! What the “other side” says is that is exactly offset by funds flowing to future bondholders. The difference is this: in your credit card example, the family only has the obligation to pay. Someone else has the right to the stream of payments. With domestically held debt, BOTH the people with an obligation to pay AND the pay with the right to the stream of payments are in the future generations we are examining.

This “insight” you are having above actually makes me think you’ve have never really gotten the argument of Lerner et al in the first place, rather than that you have gotten it and now transcended it.

No, absolute not, Gene. I get exactly what Lerner was saying. Here’s why you are wrong:

Take the analysis a little further. When the government issues the $10,000 IOU today, “future taxpayers” are now holding an extra liability, in the amount of $10,000. Who has the counterbalancing asset? The government does. It got $10,000 in cash from a lender. The lender broke even; he swapped $10,000 in cash for a $10,000 IOU.

Now it’s true, the government today can do things today to *offset* this gross burden that it just created for the future taxpayers. For example, it might build them a bridge. Or, it could stick the $10,000 in a piggybank, so that the future taxpayers would directly inherit this asset from the government and it would partially offset the liability they inherited from the government. Or, the government could give a transfer payment to old folks, who in turn end up bequeathing more to their children, so that the gross burden of the extra $10,000 in offset that way. But if that $10,000 in extra debt issued by the government, corresponds to an increase in consumption of someone in the community by $10,000–that is exactly counterbalanced by the lender to the government consuming less, and investing in the $10,000 IOU–then future generations don’t inherit anything to mitigate the gross $10,000 burden that the IOU imposed on them. This is simple balance sheet accounting. I feel bad, because MF was telling me to do this from Day One (or maybe Month One), and I ignored him because I thought it was too simplistic (and plus his posts would take 64 generations to read). But he was right. When you think about it in balance sheet terms, it is crystal clear what is going on.

Here’s where you are going wrong, Gene: You are thinking that the people who lend money to the government today are bearing a “burden.” OK yes in one sense they are, and I’m not denying that sense. But they are not made poorer by doing so. No, they break even. They swap $10,000 in cash for $10,000 in government bonds.

So what really happens when the government today issues an IOU, in the very act of doing that, is that the government of today increases its assets at the expense of future taxpayers.

Anyway, say whatever else you want about me, Gene, but don’t say I don’t “get” the point about foreigners holding the debt, etc. I was the one going nuts when Landsburg kept saying, “Yep Krugman is right, though he forgot to mention that even foreign ownership of debt is irrelevant,” remember? The reason I understood the stress Krugman and Baker were putting on domestic ownership of the debt, is that I totally get this point. I used to believe it myself. And now I think it is extremely misleading at best, and flat-out wrong at worst.

This is simple balance sheet accounting. I feel bad, because MF was telling me to do this from Day One (or maybe Month One), and I ignored him because I thought it was too simplistic (and plus his posts would take 64 generations to read). But he was right. When you think about it in balance sheet terms, it is crystal clear what is going on.

Well, I do post primarily for posterity reasons (remember? I post on Sumner’s blog for readers 50 years from now? heh).

Considering how I saw a dividend already one year in, I’m pleasantly surprised (seriously). No need to feel bad.

In case anyone wants to read the post in question, here it is.

+1

“What the “other side” says is that is exactly offset by funds flowing to future bondholders.”

Wat the “other side” is missing is that unless the future bondholders get the bonds for free, the funds flowing to them are offset by the money they paid for the bonds.

So only if the current bondholders give the bonds to future bondholders for free (or the debt is repaid to the current bondholders) will the debt not be a burden on future generations.

There is one thing that you are wrong about.

You’re logic is this.

Future generations are done over. I agree with this and your logic.

That means current generations are winners. That’s a major assumption, and you’ve not thought it through.

For example both current and future generations can be losers, because past generations were the winners.

That is the case. Past generations won, current retirees and future taxpayers are the losers.

Technically true, but how is that an argument against anything Bob Murphy said?

If the government issues debt it can’t transfer benefits to generations that lived before the debt was issued.

It’s true past generations could be the winners, but that’s because the government issued debt in the past.

And even with past generations being the clear winners, present issuing of debt could make present generations winners relative to future generations.

I’m a bit shocked everybody is trying to corner Dr Murphy with little gotcha comments. Even if he made a techincal mistake somewhere Krugman, Kuehn, Callahan, Landsburg, et al have been saying much more outrageous things and no one seems to be giving them a hard time over that.

It’s a subtle but important point.

Governments are setting this out as a future generation against current generation battle. One side is more greedy than the other, when both are in fact victims.

Governments are doing this because they don’t want people to really find out what has gone one. Namely the state has embezzled money on a scale that is unimaginable. Secondly, they hope as individuals to have taken the money and run before the shit hits the fan.

For example, I FOI’d the Treasury in the UK, asking them about the present value of the state pension debts. Their reply was, we have two emails on the subject, both about how to deny there is a debt. Given that its 2,500 bn based on some research I’ve done based off other FOI information, its quite a major point

It’s going to be the same in the USA.

Nick

[1] I got ages, sexes, number of years entitlement against the number of people in each category, along with the same for people already receiving a state pension. That enables a pretty accurate present value of the amount owed to be calculated.

[2] I also did a back test of what contributions would have achieved if invested. The result is they are only paying out 20% of the value of contributions

Shouldn’t the final column be 6,7,8,9,9,9,6,3,0,0 ?

nvm

First I want to identify clearly a few bones of contention.

Krugman said that while debt can cause a transfer scheme, like a Santorum tax can cause a transfer scheme,

*aside from that* the internally held debt represents no burden on or direct impoverishment of the nation as a whole in the future.

And Bob says that claim is wrong, and the debt per se causes a burden and impoverishes the nation.

Are we all agreed so far?

Bob presented a model, actually an ever changing series of models, claiming to show Krugman was wrong.

So, in terms of those models what do you need to show to disprove Krugman (ie to exhibit a counter example to Krugman’s implied lemma).

The most natural interpretation of Krugman’s claim is the total assets of Apple Island at any single point in time in the future is constant.

And by construction Krugman is right about that. Look at Bob’s models — pick one —

and you will see that no matter what the loans, taxes, payments that the total assets of the island never vary.

Bob tries to sidestep this conclusion by reinterpreting what Krugman meant. Bob does not look at the assets of the nation at any one time.

He sums the assets of just some of the individuals alive suring a period of time, over a period of time.

Let me illustrate. In today’s chart for example he sums Hank and Iris over their lifetimes, and gets 17 each.

In detail he adds Young Hank + Young Iris + Old Hank + Old Iris.

But he ignores some of the people alive during this period: Georege (when old) and John (when young).

This doesn’t correspond to Krugman’s assertion.

It’s just not using the right limits of integration, it’s like refuting the conservation of momentum by ignoring some particles or counting some twice.

Not only does it not correspond to Krugman’s assertion, the “burden” is not caused by the initial borrowing. I will return to this.

Now I will admit that Krugman’s wording in a later post was vague, when he talked about ‘future generations’. But I think the

natural reading of that again involves an integral which includes everyone alive on the island.

After all PK is arguing from the fact that the debt is internally held, so his constraint applies over the whole container.

You can’t ignore the limits of his constraint and claim a counter example.

Again an example. Imagine two columns and several rows where each row sums to 200.

A B

C D

E F

If you look at just the sum B + C the only constraint is that it be between 0 and 400.

There is an even looser constraint on B+C+D+E.

Calculations that try to evade Krugman’s constraint this way cannot really be said to be directed at Krugman’s intended meaning.

As for debt being a burden apart form and above transfers … Let’s consider a hypothetical.

There is no debt. Instead there is Christianity.

Some members of society are overcome with a desire to give whilst young,

and to insist that when old they receive less than they gave.

And their pattern of giving reproduces Bob’s chart today.

Or indeed any of the charts. Any of Bob’s charts can be reproduced this way.

In this example we see the same “burden”. The same folks consuming fewer apples.

And it is not from debt is it? It is from wealth transfers.

Debt is only a motive for the transfers. As is christian giving.

So the alleged burden due to the debt is in fact reproducible just by transfers, and indeed by voluntary ones.

That shows that the burden is caused by the transfers not the initial debt.

Which is exactly what Paul Krugman (and Abba Lerner, and Gene Callahan, and Steve Landsburg, and me) said.

You are omitting that Krugman didn’t make his claims out of the blue. He wanted to counter the average Joe “fallacy” that running up debts might impoverish his children in the average. Either Krugman wants to say this is wrong, which it clearly isn’t as all of Bobs models obviously show, or it was Krugman who pulled a strawman by arguing only about GDP per period but not about the actual wealth of the people receiving less lifetime consumption…

Actually as I have noted more than oncer I DO think there is context missing here. The question is: GIVEN that there will be govt spending X is there a GREATER burden financing the spending through internal borrowing or contemporary taxation? That’s the question really being debated. That extra context does not bolster Bob’s case. Quite the reverse as to prove his case he needs to carefully comapre the two approaches, and has not. Landsburg did, and came down on PK’s side.

No this was NOT the question. It was the question WHO is burdened not which method burdens more on net…

Please describe to me in your words what the average Joe fears about governments running up debt.

Look at Bob’s models — pick one —

and you will see that no matter what the loans, taxes, payments that the total assets of the island never vary.

Bob tries to sidestep this conclusion by reinterpreting what Krugman meant. Bob does not look at the assets of the nation at any one time.

Ken, are you arguing that the total financial wealth–before they pop the apples in their mouths–of Al and Bob in period 1, is the same as the total financial wealth of the two people living in (say) period 6?

Sneaky Bob. I am arguing the total available stock of apples available to be eaten in period 1 is the same as the total available to be eaten in period 6. Even Christian giving can’t change that.

Sneaky Bob. I am arguing the total available stock of apples available to be eaten in period 1 is the same as the total available to be eaten in period 6.

Yes Ken, we all know that. That was done on purpose, to show that someone who thinks real apples available in each period IS THE SAME THING AS:

Bob does not look at the assets of the nation at any one time.

…is wrong.

So everyone, Ken B. has just clarified: If we ignore the fact that government bonds entitle people to future payments, then government bonds don’t affect anything. Yes that’s true. And if I give a farmer Gene’s car, and we only count chickens, then I haven’t made the farmer wealthier at the expense of Gene.

Ken B. wrote: “ook at Bob’s models — pick one —

and you will see that no matter what the loans, taxes, payments that the total assets of the island never vary.

Bob tries to sidestep this conclusion by reinterpreting what Krugman meant. Bob does not look at the assets of the nation at any one time.”

Ken B., you are demonstrably wrong. Look at the latest example here. In period 1, before they pop the apples in their mouths, what are the total financial assets of the people on the island? Al has 16 apples, and Bob has 4 present apples plus property entitling him to (after-tax) 17 future apples.

Now skip ahead to period 7. George has 19 present apples, while Hank has 1 present apple and property entitling him to (after-tax) 16 future apples.

So in period 1, total assets held by the islanders is 20 present apples and 17 future apples.

In period 7, total assets held by the islands is 20 present apples and 16 future apples.

20 = 20, and 17>16. So the people in period 1 have larger assets, measured in real apple terms, than the people in period 7.

On the very criterion you just gave us to see who was right, you lose.

And now you will shift the goalposts yet again… “No Bob, what you continue to ignore is, there are the same number of apples each period. There’s no time machine! Krugman was arguing…”

You aren’t varying assets. You are varying labels on assets. That’s a very different thing. Who for instance is Younf Dave to sell this note to in period 3.

Let’s like amnesiacs for get the chart in periods 1 through 6. What happens from then on? The transfers , by your argument, start making the country richer. But you don’t really believe that do you?

But you also haven’t pointed out anything Gene or I have not pointed out. Gene eats his son’s desert, and gives him an IOU. Now years later Gene’s son can take a desert from his own son, but that isn’t caused by Gene’s labelling the purloined pudding with an IOU.Unless his on actually takes the pudding next time the loss stops at Gene’s son, whose life overlaps Gene’s life.

Ken B. wrote:

You aren’t varying assets.

Ken, suppose I have a Treasury bond that will pay $1000 in 2013. Are you saying that’s not an asset to me RIGHT NOW?

When you make a claim like “Bob hasn’t shown that total assets can vary,” and I demonstrate you are wrong, at least have the decency to say, “OK you’re right, what I should have said was…” Don’t have the audacity to tell us bonds aren’t assets.

In a world with one good and no inheritance, where your only customers will die before the redemption date?

Plus don’t yopu see the double counting you are trying? You want to count the claim on the future apples and then claim them as present apples too. Look at my momentum discussion …

No, we’re talking about present consumption of apples and present claims on future consumption of apples, which are both valued as assets that make individuals feel wealthier (and they are, to a degree), but when looked at from the perspective of the economy as a whole, AND over time, then no, there is no increase in goods. But that doesn’t mean that entire generations are not burdened due to the introduction of taxes that reduces assets without a corresponding increase in assets.

Taxes without debt does not reduce assets in the economy.

Taxes to pay back government debt does reduce assets in the economy.

Since it is the debt that initially increased the assets that are later on in future generations destroyed, we ought to accept that it is the debt that burdened the people, not the taxes.

Ken B. wrote:

The most natural interpretation of Krugman’s claim is the total assets of Apple Island at any single point in time in the future is constant.

No Ken B., the most natural interpretation is that physical output of the nation at any time in the future is constant, and Krugman is *correct* in saying that. But when you switch to “so therefore the total assets of the nation” or “therefore the wealth of the nation” or “therefore the well-being of the nation” is also unchanged at any future time, you are wrong.

It was precisely this distinction that I myself didn’t see, until Nick Rowe blew up my world.

We aren’t talking welfare Bob, because you and I agree that with the right utility function any transfer can lower or raise utility .

It’s not necessary to change the utility function.

To the extent that assets (government bonds) are positively valued, there is an asset introduced into the economy without no CURRENT liability anywhere. That liability is transferred to the future. Once the liability stream is finally manifested (taxation), that’s when assets fall with no corresponding increase. If at a given period of time, a liability is introduced with no corresponding asset introduced, is that not a burden to an entire generation in the Krugman sense?

Are we all agreed so far?

No. Bob never claimed that “the nation” loses. He always agreed with the stipulation that cross-sectionally there is no change to GDP (apples) caused by the debt.

He is making a point about EVERY SINGLE INDIVIDUAL past a certain point in time experiencing a lower lifetime consumption, which Bob insists is a reasonable interpretation of “future generations”.

His other main point is that because Krugman’s readers are not being told that debt MAY reduce the lifetime consumption of every individual in the future, that they are being led to believe that debt cannot be a burden to every individual in the future as per the OLG model.

In other words, if Krugman’s readers were armed, so to speak, with the OLG model, then they may go from not caring about the national debt at all, to caring very deeply about the national debt, because they had no idea it was possible for every individual in the future to experience a reduction in consumption, because of years of being told rather vacuous platitudes such as “we owe it to ourselves, so no big deal”, and not thinking about it more.

We’re not agreed that Bob says Krugman’s claim is wrong?

No, we’re not agreed that Bob claimed the NATION loses. Bob has been saying INDIVIDUALS are losing.

ALL individuals, mind you.

Didn’t I just post an example of how Christian giving can hurt all individuals in the same way? But that’s not what PK was saying and Bob says PK is wrong. We all agree that Bob’s scheme of 65 sequenced transfers leaves 65 sequenceds losers. Re-read Gene on deserts, or several of my longer comments.

Didn’t I just post an example of how Christian giving can hurt all individuals in the same way?

No, you did not, because it’s all voluntary in that example. There is no “hurt” there, despite the fact that consumption is reduced for each individual.

By your logic, I’d have to say that because you can “replicate” mass genocide by way of mass suicide, in the mechanical sense, that mass suicides do not cause deaths.

PK is saying that because all taxes and all government debt can only result in MONEY transfers from one group to another, that this means future generations cannot be burdened.

Rowe and Murphy grant all that as far as it goes, but they point out that government debt can reduce the lifetime consumption of all individuals in the future.

Bob tries to sidestep this conclusion by reinterpreting what Krugman meant.

This is misleading. How do you know it’s “reinterpreting what Krugman meant”, as opposed to making a new argument that neither Krugman nor his readers know about, that can be reasonably interpreted as “future generations”?

I have explained at length and in detail why. It’s the plain common sesne reading of PK’s words. Look back at my explanations on other threads.

I already did as those comments were made, and they were wrong then too.

Bob isn’t trying to “reinterpret” what Krugman said. Bob agrees with Krugman that cross sectionally, i.e. “the nation”, there is no necessary reduction in goods (always 200 apples, remember?).

Bob and Rowe specifically made the OLG model to have what Krugman said happens, no change to cross sectional goods. 200 apples each and every period.

Again, the fact that you are still writing what you are writing at this stage only shows you never truly got the point of the OLG model.

“The most natural interpretation of Krugman’s claim is the total assets of Apple Island at any single point in time in the future is constant.”

The whole point of Bob’s Apple Island models is to show that it is possible that the total assets are constant at any single point in time in the future (and present) while it’s still the case that a generation (or more than one) benefits at the expense of one or more later generations.

Which oddly enough was the point of my Christian charity example too. Demonstrating it’s not debt but transfers which cause this effect. Debt is just one possible *motive* for transfers. See some of Gene’s posts for this point too.

That’s like saying falling out of a 10th story window won’t kill you… hitting the pavement will.

Or: pushing someone out of that window isn’t murder since he could have jumped out.

Or: buying a house with a mortgage doesn’t cost money, amortization will.

No. It’s like saying debt is a motive for transfers. There are lots of motives for transfers. If debt causes the losses in Bob’s example with debt then *christian charity* causes the losses in my example with the spirit of christian charity abroad in the land. I have changed Bob’s example in only one regard after all, subbing charity in for debt.

If debt causes the losses in Bob’s example with debt then *christian charity* causes the losses in my example

Who would say it doesn’t?

I suggested to Bob that he wouldn’t and he did not demur. But you’re right that’s just an inference on my part, possibly mistaken. We should ask Bob.

Bob?

Plus Martin Krugman’s position is that *transfers can cause problems* and *incentives can cause problems* and that debt causes problems *only because it leads to transfers and incentives*. If Bob wants to say PK is wrong he needs to show a cost from debt not attributable to the transfers or incentives. He created a model without incentives. He did not create one without transfers.

Look at what PK said about the Santorum tax.

No, that is not right that Bob’s model is working without incentives. Only incentives to produce wealth are switched off by assuming a fixed apple production.

Else incentives are still in play. Please reread Bobs The economist Zone post. It should be clear that there are incentives working. It is called living on the expense of future generations while politicians abuse this incentive to buy votes.

People are really not eager to finance the same scheme with normal taxation or your superficial charity scheme.

The incentive is better called the “have something for nothing incentive”, since the people in Bobs example really do care about their children and only agree to this debt scheme when they have been convinced that neither they are paying for it nor any later generation…

But those positions are not the issue here. The issue is:

Before I do so, I want to be clear on what I’m trying to prove: Paul Krugman and others (a group that would have included me, two weeks ago) think that only the naive layperson could think “running up the government debt allows us to selfishly live at the expense of our grandchildren.”

Bob’s model (or my simplified model here) shows how you can live at the expense of your grandchildren. Shure that involves a transfer. By definition I would say. If A lives at the expense of B that’s a transfer from B to A.

GREAT JOB MARTIN! It’s great to see that my position back in January (after Rowe blew my mind) is the same thing I’m writing today. And Gene and Ken B., check out this old Landsburg post. He is clearly saying that he agrees with Krugman’s position on debt not being a burden, but he doesn’t think Krugman’s focus on the internal/external financing is the key. Thus, my claim that Krugman and Landsburg are using totally different arguments to reach the same conclusion. (Landsburg’s argument is plausible, Krugman’s is not.)

A debt without a transfer is not a debt.

It is inherent in the model that when the debt increases the elder in that generation has a lifetime consumption above 20 , and when the debt is paid down they will have a lifetime consumption below 20 so its not surprising that one can build a model to show this.

Whether the debt does increase or not is entirely exogenous to the model (ie it is controlled by the “govt” if one wants to see it that way ). and it is this rather than anything inherent in debt itself that causes the income distribution we see in this model.

It would be possible to create a model where an increase in debt would not increase the utility of the elders in the present generation (for example if the elders could buy bonds and give them to their children, or if the debt led to a decrease in consumption in the present and an increase in the future). One could make a case that such a model would more accurately reflect the real world.

First para should read

“It is inherent in the model that when the debt increases the elder in that generation has a lifetime consumption above 40 , and when the debt is paid down they will have a lifetime consumption below 40 (if tax is only used to pay down debt) so its not surprising that one can build an example to show this. “

Why are we considering bonds to be assets?

Artificial expansions of the apple supply are not assets; And when “spent”, they are a pure transfer, not a trade.

Sometimes my magnanimity astounds even me. Ken B., Gene, et al., I am wondering whether my critique of MMT in any way contradicts what I’m saying to you guys, now. I.e. the MMTers argue that when the government issues IOUs today, they are making the private sector wealthier. It’s possible that (because of the OLG complication) I said this was wrong against them, and now I’m saying it’s right against Krugman.

I imagine Ken B. if there is a contradiction, you will find it. Here you go, release the hounds!

Don’t worry, I made sure there is no contradiction between the Austrian critique of MMT before I spoiled the apple basket with a balance sheet analysis that includes assets like government bonds.

When both the asset side AND liability side to government debt are considered, then no, government issued IOUs do not make “the private sector” wealthier. After all, the private sector exists both cross sectionally (space) AND temporally (time). The “private sector” in the OLG model is all 65 generations. It isn’t just generation one.

Don’t worry so much! If you made the argument that a person consuming their own body whilst stranded on a deserted island increases their welfare, then sure, if we abstract away from the future consequences of doing that, then MMTers are right. But granting the fact that eating yourself is a “benefit”, does not obligate you into accepting the MMT argument that people eating themselves makes people better off in a more general sense that includes their future deteriorating selves.

We humans are not entities that exist in space. We exist in spacetime. The private sector is weakened over time by government debt, despite the fact that everyone “feels” richer.

It’s akin to capital consumption. Go back to your sushi model. You agreed that consuming capital makes everyone feel “richer”, and that yes, output really does increase…for a short time. But the sushi economy is being weakened and future people are going to feel the hurt. Thus, consuming capital cannot be seriously claimed as activity that “benefits the private sector”.

The key is that government debt makes people FEEL wealthier. It doesn’t mean they ARE wealthier! This is also connected to ABCT. ABCT grants that credit expansion does make the private sector feel wealthier…..for a time.

“I imagine Ken B. if there is a contradiction, you will find it.”

I’ll just go with the odds here Bob. You’re wrong both times.

🙂

Speaking of magnanimity, thanks to (most) posters here for a good discussion, especially Gene Callahan for cogent logic pithily put.

Ken B. wrote:

The question is: GIVEN that there will be govt spending X is there a GREATER burden financing the spending through internal borrowing or contemporary taxation?

Yes, of course there is a greater burden on future people if the gov’t in period 1 finances the transfer to Al with a deficit instead of a direct tax on Bob. In the former case, the gov’t finances the transfer by taxing Christy through…[last person to get taxed before debt is paid off], rather than taxing Bob.

Ken, GIVEN that the government is going to spend $1000 giving someone soup, does it matter to Jim if the government:

(a) taxes Jim to pay for it or

(b) doesn’t tax Jim to pay for it.

You are arguing it’s irrelevant to Jim whether he gets taxed or not. Replace Jim with “future generations.”

So yet again, Ken, you set up a criterion for who is right, and you utterly fail. But you will now point out, “OK sure, Bob, I’m 0-for-2 on my own criteria today and it’s not even lunch time. But you’re not realizing that in your model, there are 200 apples every period. See what I’m saying?”

This is what’s funny, Ken. You don’t understand Landsburg’s position either.

Landsburg would agree that by issuing IOUs today, which are claims on future taxes, you are burdening future taxpayers. But he is saying that in a reasonable model, the beneficiaries of the gov’t spending today, will adjust their bequests accordingly to perfectly offset what happens to future people, so ON NET they aren’t burdened. (This is also why foreigners holding our debt in the future, doesn’t affect Landsburg’s argument. He is saying Americans today, end up bequeathing more to Americans in the future, if they financed gov’t spending today with foreign money rather than internally. This shows that Landsburg is NOT making the “debt just moves stuff around if it’s held internally” argument that you and Gene and Lerner and Krugman are making.)

Nobody except you, Krugman, Abba Lerner, and Gene are insisting that it is irrelevant to future people whether they are taxed or not to pay for our spending today.

http://www.thebigquestions.com/2012/10/13/krugman-so-right-and-so-wrong/

You know what Bob, this part sounds like Steve is talking about the internal stuff:

His bold.

You know Steve personally. Ask him to respond.

Ken I don’t want to because Steve doesn’t usually respond when I send emails on the debt posts, and I’m afraid I’m annoying him. You can ask him. But it’s funny that you have to put in ellipses in your quotation, to weed out the fact that Steve was address what Krugman did NOT say. I.e. the innocent reader would think Steve was just reproducing Krugman’s point, when no, Steve was saying “Now Krugman for some reason forgot this obvious point, so let me make it.”

Thus, my point: Steve is “filling in” something that actually contradicts what Baker and Krugman said.

Ellipses were for brevity Bob. I provided a link, anyone can see SL is supporting PK on the point at issue here.

I will ask him, but I’ve never met the man.

Just to clarify for everyone: Landsburg said (paraphrasing), “Krugman is right that the debt doesn’t burden future Americans. He makes the argument in terms of future Americans holding the debt, but I want to generalize to show that even if future foreigners hold the debt, future Americans aren’t hurt.”

But, if you go read Krugman’s past writings (and Abba Lerner and Gene Callahan are even more explicit on this), it is clear that the *internality* of the debt is key to their whole argument. That’s why Krugman e.g. has other posts showing that the trade deficit didn’t do much in the period in question, blah blah blah.

So, Steve is agreeing with Krugman’s conclusion, but via an argument that actually contradicts what Krugman is doing. I can’t explain why Steve does this, except to say, Steve is so happy whenever someone defends deficit financing from man-on-the-street prejudices, that Steve doesn’t even care if the argument is the same one he would use.

I think the model is more complicated than it needs to be. How about this one:

Period 1: G borrows from Bob 1 apple at 0% to be repaid in period 2. G gives this apple to Al.

Period 2: G taxes Christy 1 apple and pays off Bob.

Subsequent periods: everything back to normal

Al is better off than he would have been without the government borrowing

Bob is no better off than he would have been without the government borrowing (he’s equally well off in terms of apples, maybe slightly well off in terms of utility)

Christy is less well off than she would have been without the government borrowing

You can either include Bob in the first generation or second generation, the second generation – consisting of either Christy alone or Christy and Bob together – will be less well of than without the borrowing.

Now you can make Bob gain by raising the interest rate, but everything he gains that way is offset by Christy being taxed for that, so on net that’s not going to change anything.

I have yet another way of showing that Gene’s critique of Nick Rowe is wrong: According to Gene, Lerner and Krugman knew full well that through deficit finance, one could appear to make everyone alive today eat more apples and get higher utility, while making every single person born from now until the debt is paid off, eat fewer apples and get lower utility.

But, Gene says that this doesn’t count as “debt burdening future generations” in Lerner and Krugman’s book, because the government at each period could replicate the same outcome without using debt at all.

OK, but now I go for the jugular: Lerner, Krugman, and Gene all agree that if the government today BORROWS FROM FOREIGNERS then it *can* impose a burden on future Americans.

But hang on a second! Write out the consumption pattern of all Americans when the gov’t in period 1 borrows from foreigners, and then in period 8 (say) the gov’t taxes Americans to pay off the foreigners. Now, I can replicate the exact same thing, if the Japanese gov’t in period 1 taxes its people and makes a transfer payment to the US government, and then in period 8 the US gov’t taxes Americans and makes a transfer payment to the Japanese gov’t.

So boom, on your own reasoning, Gene, I just showed that borrowing from foreigners can’t impose a burden on future generations. Thus, this is clearly not what Lerner and Krugman can mean. They are making a distinction between internal and external financing that only makes sense if they deny the type of thing going on in Nick Rowe’s apple model. They weren’t making the philosophical argument that it’s not “debt per se” causing pain, if you can replicate the same outcome in some other combination of gov’t actions.

(To repeat, Lerner and Krugman CAN’T be making this argument, because if they were, they wouldn’t concede that borrowing from abroad can hurt future Americans, either. And this is why I’ve been saying that yes, *Landsburg* is saying something like this argument, Gene, and that’s why he doesn’t care who finances the deficit. But Lerner and Krugman were NOT making this particular argument, and that’s why they thought it was crucial that the financing be internal.)

BOOM! Head shot.

Folks, this post right here SHOULD settle who was right.

I’d kinda like to hear from Krugman on these examples. Maybe Bob should debate him!

Why I oughta….

Ken, am I understanding you right: You think that because you showed that a voluntarily chosen donation can burden the giver, and benefits the recipient, that you’ve contributed something to this debate? *That* is supposed to show that Krugman was right for thinking that debt today CAN’T burden future generations?

I.e. you seem to expect me to say, “No, no, I take it all back! Ken has just shown me that if I write a check for $1000 to my church, that I have made myself $1000 poorer. I can’t accept that, so I admit I was wrong in my debate with Krugman.”

You’re really putting up a good show today, Ken. Plus I like the implicit jab at my religious beliefs. You could’ve picked just regular old charity, but no, you had to specify Christian charity in your non sequitur, for style points.

Ken is attacking his own drive to believe in a creator, using you as a conduit.

You are once again misrepresenting what I showed and claimed Bob.

Style points? Soitenly!

“No, the point is that what matters is resources, not debt.” Guess who?

Anyway Noahpinion has an interesting post.

Here’s some of his conclusions, with which I agree:

” no matter what transfers happened in the past

or how much government debt we have today, then given some simple assumptions,

it is always possible to get away with only screwing people who are currently alive

…Given some more simple assumptions, it is always possible to limit the total amount of screwage

(in consumption terms, not utility terms) to the amount of consumption that was, in the past,

transferred away from people who are currently alive. ”

This is all certainly true of Bob’s examples.

Noah’s post is here http://noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2012/10/debt-and-burden-on-future-generations.html

I don’t see how any of those propositions implies, “Gov’t debt today can’t burden future generations on net.” It actually seems that Noah is trying to characterize just *how much* previous actions can screw people current alive.

(And in fact, after a back-and-forth Nick Rowe didn’t have a problem with Noah’s post.)

ima newb at this, but if the goal is to have a debt thats balanced, isint that the same as no debt? with just a system of lending, that does not get out of control? the idea of necessary debt seems counter intuitive to prosperity. whats the opposite of debt, surplus? why cant we have a balanced surplus? i realy dont think, no matter what, the we need debt. i really dont know all the politics of it. but they all seem useless 😀 haha

I actually should have shown a surplus too, to see what happens…

Can a debt *enrich* the future? By Bob’s criteria it can.

Let’s look at the example of Apple Atol, just a few miles from Apple Island where their policies differ.

In period 1 govt borrows 1 at 100% from young A for old Z.

In period 2 govt borrows 2 at 100% from young B and pays off the loan to old A.

In period 3 govt borrows 4 at 100% from young C and pays off the loan to old B.

In period 4 govt borrows 8 at 100% from young D and pays off the loan to old C.

In period 5 govt borrows 16 at 100% from young E and pays off the loan to old D.

At this point the Atol switches policies to get a steady state. There are many ways to do this.

Govt can tax the youngster 8 and borrow from the youngster 8 at 100%, or borrow from the youngster 16 at 0%.

Let’s use the latter.

In period 6 govt borrows 16 at 0% from young F and pays off the loan to old E.

In period 7 govt borrows 16 at 0% from young G and pays off the loan to old F.

In period 8 govt borrows 16 at 0% from young H and pays off the loan to old G.

etc

I lack Bob’s mad table skills but let me show the resulting data

oq 100 yz 100

oz 101 ya 99

oa 102 yb 98

ob 104 yc 96

oc 108 yd 92

od 116 ye 84

oe 116 yf 84

of 116 yg 84

oh 116 yi 84

Now let’s do Bob’s diagonal sums.

Everyone ends up with at least 200, and some end up with more than 200. C gets 204.

The future, by Bob’s critria, has been enriched.

A few other things to note. This example runs on pure debt, not defaults and not taxes, but there are several ways to produce such examples.

Old Z is better off too, no-one is harmed.

By the Krugmanite criteria, the Atol is not enriched.

For style points, the govt can just destroy the apple it borrows from ya.

Then the chart changes to “oz 100 ya 99”

That leaves Z out of the windfall, but the Bob-defined enrichment still works with no-one losing out *even with an apple destroyed*.

By the Krugmanite criteria the style points apple destruction impoverishes the present, without aiding the future. Broken windows anyone?

I suggest this example shows Bob’s crtiteria are wonky, and that the limits of integration are inappropriate.

I forgot to add: for extra style points, the govt can destroy apples in some periods, like the period where old D gets paid off, and Bob’s criteria still show enrichment.

Ken,

If I can show you a hypothetical scenario where there is no cross sectional generational reduction of total private property, and then ONLY introduce government debt into that scenario, that is, I do not change the amount or timing of taxes, I do not change the amount or timing of production, I do change anything except I add government debt, after which I show there is a cross sectional reduction in total private property, then would you accept my assertion that I have shown that debt per se can be a burden on an entire generation, cross sectionally, the way Krugman et al denies?

Too many hypotheticals to follow, especially in a debate largely about interpretation not facts. Show it, explain what you mean, and we’ll see. I suspect you want to count labels not real goods.

Just reducing private preoerty alone won’t do it though. On apple Island in Bob’s initial condition, a new govt nationalizes all apples and feeds everyone 100 each period. That’s the same result as the laissez faire with less private property and no I would not see that as refuting PK.

But don’t forget to address the issues my example shows.

I suspect you want to count labels not real goods.

I don’t know what you mean by “labels”.

Real goods was always held constant at 200 apples per year, even in the OLG model, and I said it will be held constant in my two scenarios as well. Real goods was never a bone of contention for anyone.

I am talking about total private property.

—————————-

Just reducing private preoerty alone won’t do it though. On apple Island in Bob’s initial condition, a new govt nationalizes all apples and feeds everyone 100 each period. That’s the same result as the laissez faire with less private property and no I would not see that as refuting PK.

That is not a reduction of total private property though. That is an unchanged total private property. Each period, you are saying the government gives 100 apples to everyone. That means each period total private property is at least 100 apples. It actually doesn’t matter that the government nationalizes all apples. The fact that the government later gives 100 apples to everyone introduces 100 apples of total private property.

Remember Ken,

Krugman has, since day one, included government debt itself as an asset, and said that to the extent these assets are owned by Americans, “we owe it to ourselves”, and so any taxation that is used to pay back bondholders cannot generate a cross sectional burden to anyone.

He said that because the taxation liability of government debt has a corresponding asset side, there is no burden.

In other words, Krugman would say that even if production in unchanged in the US, but government debt is owned by foreigners, THEN there would be a burden to Americans. That means he is not just considering “real goods” when he talks about burdens.

So again I ask, if I can show you an actual reduction in property, that includes the very kinds of things Krugman included in his analysis of burdens, then would you agree that “debt per se” is the cause for the burden and that Krugman is wrong?

Or maybe I just made the mistake of assuming unchanged CONSUMPTION in the US.

Krugman would probably say that the debt owned by foreigners can reduce consumption for Americans, because the interest they earn can be used to export wealth out of the US.

Never mind.

What do you do if young F doesn’t want to give money to the government for 0%?

Please reread Bobs The Economist Zone post to understand the incentives (not the ones to produce wealth) working behind this.

http://consultingbyrpm.com/blog/2012/01/the-economist-zone.html

“…

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, I know! I’m gonna borrow 3 apples from each Bob, at a 0% interest rate, to pay for it!

CROWD: Boo!…

“

By having people prefer to consume when older. Look at Bob’s island model. He gives a U function. Tweak it a bit to get apple atol. Multiply the U of the second period by 1.5 for example.

But the logicv here doesn’t depend on that. As I said you cen use taxes and borrowing (as Bob does) or taxes and defaults (as Bob does).

Listen you can’t predetermine when people want to consume. Most people don’t want to lend money at 0% percent! And your example requires that. Bob’s does not!

As I said in another post already. It is also technically possible that a thief ambushes you in a dark alley and threatens you to shoot if you don’t take HIS money! However that just doesn’t happen. And that is for a reason.

skylien I agree with you insofar as saying debt helps people if we assume they would rather consume less when young and more than old, is kind of a weird way to win the argument. I mean, it would be like saying socialism works if people would rather eat less food than more food.

However, I made some pretty general claims about debt issued today per se making future generations worse off, and so I want to play with the model assuming strange utility functions as Ken has suggested. I’m not sure if my claim was too broad, or if even in Ken’s world, once we pick the proper baseline, it’s still true to say that gov’t issuing debt today, per se makes future generations poorer.

But I have to do that next week…

Merci. Plus of course I can do it with some taxes and 100% interest, just as Bob uses a mix. I don’t think my argument relies on using either regime.

It’s not quite so odd if we look beyondjust *my* consumption. My U function can also include the welfare of my companion when I am young. Christian charity again! Or think about medical care.

The biggest problem with those utility functions is that they will change from generation to generation.

And the problem of debt is that ones made, it is a promise for a certain return in the future to certain people,whereas those people try to factor in how much they might be taxed in the future. So they wouldn’t make loans to the government if they knew they will be taxed to pay it to themselves. And if the sustainability is based on a certain fixed utility function of all generations then this is a meaningless model in my view…

I agree that with apples it at least might be possible that one or some generations will prefer to consume more later if apples perish from one period to another. Yet this would definitely as already said not count for all generations and this point would be meaningless anyway as soon as you would introduce money instead of apples…

” When I was puzzling over this outcome, something obvious occurred to me: What does it mean in financial, balance sheet terms to run up the government debt? I don’t even care what is done with the funds. Just focus on the act of the government printing up an IOU for, say, $10,000, and giving it to somebody who is alive today. What just happened, in financial accounting terms? Why, the recipient of that new bond gained an asset with a market value of $10,000. So somebody else must have lost. Who? The government, sure, but more strictly speaking it is the future taxpayers. ”

Yes (ahem): http://consultingbyrpm.com/blog/2012/01/new-ways-of-understanding-the-debt-burden-dialog.html#comment-31899

Who? The government, sure, but more strictly speaking it is the future taxpayers. ”

=================

Not necessarily.

It’s down to the use of the money borrowed.

If that money is used to reduce spending but maintaining services by more than the cost of borrowing, then people are overall better off.

However. that’s not the case. The money is borrowed and spent, and the benefit of the spending is less than the cost of the borrowing.

Here’s another way to see it’s the transfers, not the borrowing, that matters.

In period 1 govt borrows 1 at 100% from young A for young A.

In period 2 govt borrows 2 at 100% from young B and pays off the loan to old A. Taxes A 2 for B.

In period 3 govt borrows 4 at 100% from young C and pays off the loan to old B. Taxes B 4 for C.

In period 4 govt borrows 8 at 100% from young D and pays off the loan to old C. Taxes C 8 for D.

In period 5 govt borrows 16 at 100% from young E and pays off the loan to old D. Taxes D 16 for E.

In period 6 default. No taxes no borrowing.

oz 100 ya 100

oa 100 yb 100

ob 100 yc 100

oc 100 yd 100

od 100 ye 100

oe 100 yf 100

“…

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, I know! I’m gonna borrow 3 apples from each Bob at a 100%, and when they are old we default on the loan!

CROWD: Boo!…

”

A default on a government bond is like a direct tax, only with the difference that the young Bob’s don’t know that at the moment they are taxed but only when the government defaults finally!

Yes it is. But look at Bob’s example. Tax on the recipient. So if Bob can do it, why can’t I? Bob changes the level of interest and taxation a lot in his example.

He changes it when the debt becomes too big and the scheme is starting to fail. A bond is contract that limits what you can do in the future. At the moment the debt becomes too big and needs to be paid off (at least partially) and the government needs to tax therefore, the generations finally start to be worse off and will restrict future borrowing more and more when they say that they will not get it back.

I mean why do you think Greece is cut off from the private money market? You cannot tweak there “U” function that they keep on lending the government at 0 percent.

*they say* should be *they see*

I mean look at what you did.

In period 2 you borrow from B 2 apples to pay off A while at the same time you tax A 2 to give them back to B. That is a shell game. Don’t you think A would be pissed off by that? This is like a default on the promised interest on the bond for A?

There is nothing in for B or A or anyone…

Oh no I am wrong, that is of course like a full default on the bond for A…

Of course it’s a shell game. MY argument, is that it’s *transfers* that matter — taxes and spending. Bob’s is that debt alone imposes a burden. The whole argument is does debt impose extra costs that a transfer scheme like the Santorum tax does not. Because PK says debt is *just like* a Santorum tax.

So here’s an example with no transfer of resources yet still has debt. So where is this extra burden from the debt?

I am NOT arguing that in Bob’s example no-one is harmed.

Then what’s the point of you shell game examples?

People have the incentive to increase their utility. They cannot do it by shell games, that is why they resist such stuff (as far as they recognize them).

Bob didn’t want to show that debt always is a burden, but that it can be for future generations even in a fixed apple GDP economy. He wanted to show that you cannot categorically rule that out, like Krugman says or at least misleads his readership into thinking exactly that.

I ahve two points, with different examples to highlight each. The first is that Bob’s criteria for judging a burden are inappropriate. I’I give an example where according to Bob’s criteria the ‘burden’ makes the country richer even with apples destroyed.

The other point is that Krugman said you can have effects due to transfers, and all of Bob’s effects can be replicated with tax and spend transfers like the Santorum tax. That addresses Bob’s claim that Krugman is wrong.

(Bob disputes this reading of PK).

To your first point:

As I already said you just decided that the government can unilaterally decide for how much percent interest (in your case suddenly ZERO) it can borrow. That is in contrast to Bob’s example who assumes that this is a bilateral thing and usually will be a positive interest rate which would blow your example necessarily up at some point.

What you do is like looking into a Ponzi scheme when it is only into the first few rounds in which there are no losers found yet, and then you assume that it suddenly continues without growing out of control…

Your second point:

It just means that there is a second way how you can also get the same result. You can not only kill people by shooting them but also by throwing an asteroid on their head.

First this says nothing that with running up debt you cannot hurt future generations in a fixed GDP economy. And secondly no one worries about people being murdered by people who throw asteroids around because it is unrealistic and doesn’t happen. Just as unrealistic as people would voluntarily agree to your tax or charity or other shell game schemes. They just would say “BOO!!”

Skylien, this is pointless. You are ignoring the point of the examples. Look at Bob’s reply to you here.

Next you are not noticing I am constructing an example to show what is possible. I know you don’t see why that’s relevant but it is. I give up trying to explain why.

And you are not noticing Bob’s example blows up unless he defaults, which he does.

And you are not noticing I can have 100% interest forever if I also have a tax of 8 apples.

Ken B:

There seems to still be a mental block in your head.

You can’t refute a counter-example by saying it is not inevitable.

“this is pointless. You are ignoring the point of the examples.”

At least one thing I completely agree on. 🙂

Yes you are right. There is nothing more you are I can say at this point. So I’ll agree to disagree…