The Economist Zone

Don’t worry everyone, all that stuff about government debt and future generations is out of my system. After several colleagues have told me repeatedly that I am being obtuse on this, I realize that I’m not cut out for economics and commentary on public policy. Instead, I’ll turn to writing for TV. I have an idea for a new series called “The Economist Zone.” Here’s the pilot. Tell me what you guys think, if you have a few minutes to read it. Thanks.

The scene opens with a million people–all named “Old Al,” oddly enough–looking very sick, and a million other people–all named “Young Bob”–looking very concerned. In addition, there is a politician, and a pundit named David Brooks. Oh, and there are economists–lots of them.

POLITICIAN: The Old Als are weak and dying!

CROWD: Boo!

POLITICIAN: We need to do something to help them!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

POLITICIAN: They each deserve 3 more apples before they die!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

POLITICIAN: So I’m gonna tax each Bob 3 apples to pay for it!

CROWD: Boo!

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, I know! I’m gonna borrow 3 apples from each Bob, at a 0% interest rate, to pay for it!

CROWD: Boo!

POLITICIAN: OK, make it 100% interest! I’ll give each Bob 6 apples back in period 2 if you lend me 3 apples today!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

VOICE FROM BACK OF CROWD: But wait, how are you gonna get the 6 apples to pay us back next period?

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, I’ll tax the young Christys 6 apples each!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

VOICE FROM BACK OF CROWD: But wait, we didn’t even want to cough up 3 apples to help our elderly. Why will the million Christys next year agree to a tax hike of 6 apples?

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, because I’ll tell them that if investors ever doubt the willingness of the government to redeem its bonds, then trees will stop producing apples and we’ll all starve!

CROWD: (murmurs)

POLITICIAN: (pauses) Uh, I know! I’m gonna borrow the 6 apples from the young Christys, at 100% interest! They’ll love rolling the bonds over! If you guys want to do it this period, so will they, next period!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

DAVID BROOKS: You should all be ashamed of yourselves! If you want to give our elderly Als 3 apples each, fine, but let’s have the decency to tax ourselves and pay for it. We can’t pass on a huge debt burden to our kids and grandkids.

DEAN BAKER: Don’t listen to him, everyone. Brooks is a fool who does little but eat more than his fair share of apples every year. As a society it is impossible for us to impose government debt burdens on our children. The reason is simple, by period 3 we will all be dead. That means that the ownership of the government debt will be passed on to our children. If we have some huge thousand trillion apple debt that is owed to our children, then how have we imposed a burden on them? There is a distributional issue — Christys’ children may own all the debt while Daves’ children don’t hold any bonds — but that is within generations, not between generations. As a group, our children’s well-being will be determined by the productivity of the trees, which we all know in the real world is forever fixed at 200 apples per period.

Now don’t get me wrong, if our kids ended up owing apples to some hypothetical guys that lived in a different Excel spreadsheet across the ocean, then our kids would be burdened if we borrowed apples today. But Brooks never said a word about this hypothetical possibility, so clearly this subtlety isn’t even on his radar screen.

DAVID BROOKS: Hey I object–!

PAUL KRUGMAN: Well spoken, Dean. But let’s make this empirical for a second: Looking at the data, we see that we live in a closed Excel spreadsheet. There are no apples flowing into or out of our hands or our children’s hands. That’s why David Brooks doesn’t understand debt.

He thinks of debt’s role in the economy as if it were the same as what debt means for an individual: there’s a lot of apples you have to pay to someone else. But that’s all wrong; the debt our government creates is basically apples we owe to ourselves, and the burden it imposes does not involve a real transfer of resources.

That’s not to say that high debt can’t cause problems — it certainly can, if our politician were to do something silly like impose a tax that weren’t lump sum (can you imagine?!?). But these are problems of distribution and incentives, not the burden of debt as is commonly understood. And as Dean says, talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay apples to other children, which is a very different kettle of fish.

DAVID BROOKS: You are such a Keynesian scumb–

PAUL KRUGMAN: Please, let me continue. I can see you’re still not getting this. Instead of dealing with a hypothetical example, consider our own history: Remember what happened on the previous tab in this Excel workbook? When our Excel table had that big war with the 9-period orange growers who lived in a different Excel table? Our government emerged from that war with debt exceeding 200 apples; because there was almost no way to move fruit between tables at the time, essentially all that apple debt was owned by people who lived in our table, people like Christy and Dave and Eddy.

Now, here’s the question: did that debt directly make the whole table poorer? More specifically, did it force the table as a whole to have less apple consumption than it would have if the debt hadn’t existed?

The answer, clearly, is no. Yes, some taxpayers in the table had to pay the interest on that debt. But who received that interest? Other taxpayers. Not exactly the same people, of course — maybe Frank had to pay George. But the table was not like a home buyer who has to scrimp to find enough apples to make his mortgage payments; the table was both the borrower and the lender, and was essentially paying apples to itself.

DAVID BROOKS: Huh, I never thought of it like that. And I watch the History channel a lot, where they have documentary after documentary about those evil orange pickers and the big war we had with them. I guess I see what you mean about the Excel table just owing apples to itself collectively…But still, I can’t help worry about us burdening our descendants by passing down a gigantic debt burden that they will have to service.

PAUL KRUGMAN: Look, don’t beat yourself up; we can’t all be trained economists. Try thinking of it like this: Suppose that for some reason the Excel table temporarily ends up being ruled by a guy who is driven mad by power, and decrees that everyone will have to wear their underwear on the outside (sorry, Woody Allen reference) everyone will receive a large allotment of newly printed government bonds, adding up to 500 percent of GDP–that’s 1000 apples, a fantastic sum.

The government is now deeply in debt — but the Excel table has not directly gotten any poorer: the public, in its role as taxpayers, now owes 500 percent of GDP, but the public, in its role as investors, now owns new assets equal to 500 percent of GDP. It’s a wash.

So where’s the problem? Well, to pay interest on that debt, the government will have to raise a lot more apple revenue. Again, this is a wash — the extra apple revenue is matched by the extra apple income people receive as bondholders. Now it’s true, if we imagined some crazy hypothetical world where the politicians implemented taxes that varied based on behavior, then high debt might make the whole Excel table poorer. But fortunately in the real world, we just have lump sum taxes, so this isn’t an issue. Our real GDP–how many apples we produce collectively per period–won’t be affected by this alleged “debt burden” that’s got you so worried will hurt our kids.

DAVID BROOKS: Gosh, I admit you make a lot of sense, but I feel like I’m being hoodwinked. Surely this plan is going to foist a huge debt burden on our descendants. I mean, it has to!

MATT YGLESIAS: Dr. Krugman, sometimes you’re too tied to your academic models. Let me try a different approach on this guy; I know how pundits who have no formal training in economics think. OK Mr. Brooks, Dr. Krugman is correct to argue that so long as government debt is held within our Excel table, then it doesn’t create a “burden” on the table in the sense of draining it of apples. I think the point can maybe be more clearly made in reverse. If a few generations down the road–let’s say in period 7–George and Hank are furious at us for passing on this alleged “burden,” then they can enrich themselves at that time by telling the politician to default on the debt. Will that work?

DAVID BROOKS: Well, no! It won’t, because whoever was supposed to get paid–either George, Hank, or both–will lose out as bondholders! Ha, nice try, Yglesias.

MATT YGLESIAS: (sighs) I can see you’re not a philosopher. You’re correct to point out that it won’t enrich them if the government defaults. But that just shows why your worries are unfounded. A government borrowing apples from its own citizens doesn’t gain access to any orchards that wouldn’t have been available by just raising taxes, and by the same token an Excel table doesn’t enrich itself by its government refusing to make promised apple payments to its own citizens. It’s only when borrowing from or repaying foreigners from other tables that our table as a whole is gaining or losing access to fruit. None of which is to say that debt dynamics are a matter of indifference. Obviously people care quite a lot about which specific people possess the apples. But it’s bad weather or locusts that can immiserate the next generation, not the prospect of the next generation’s taxpayers transferring apples to the next generation’s bondholders.

DAVID BROOKS: I admit, I can’t really put my finger on what’s wrong with your guys’ argument, but to be honest I never really trusted you Keynesians who think we just need to bake some more apple pies for prosperity. I’m going to turn to this guy over here, a trusted Austrian who isn’t afraid to write books on politically incorrect stuff.

BOB MURPHY: You know it’s ironic, Mr. Brooks, normally I can’t stand what these three knuckleheads say about government policy. But in this instance, I think they are technically correct. Although I’m against this deficit spending plan because I don’t think it’s fair that anybody down the road gets hit with an involuntary tax on his apple crop, even so I have to admit that the scheme won’t make our descendants on net poorer. Some grandkids might be poorer because of the tax bill, but–like these guys have been saying–those apples will just go right into the mouths of other grandkids. I mean really, it’s not like we have a time machine, for crying out loud! We can’t literally take apples away from our descendants and eat them today. Every period, no matter what we do, there are 200 apples produced and consumed. All the government down the road will ever be able to do to our descendants is rob one to enrich the other; it can’t make them all collectively poorer than they otherwise would have been. It’s not like we’re dumping chemicals in the soil that will reduce apple output in period 3 or something. It is physically impossible for us to affect what happens to the people collectively in period 9, because we know that no matter what, the two of them will eat 200 apples total. If one person eats fewer because of taxes to service the debt, then necessarily the other person will eat more apples.

Don’t misunderstand me: In a hypothetical world where we could cut back on our apple consumption today, in order to plant more apple trees and raise total apple output in (say) period 5, then this immoral scheme would also objectively make our descendants poorer. But in the real world, where we have no such growth in real output, this isn’t an issue.

DAVID BROOKS: You spend time thinking about hypothetical worlds where apple output increases over the time periods?

BOB MURPHY: Once you start thinking about apple crop growth, it’s hard to think about anything else.

DAVID BROOKS: Well, I guess that’s that. If the Keynesians and Austrians agr–

DON BOUDREAUX & NICK ROWE: Stop!! This is all totally wrong!! Buchanan showed us why!! There was nothing wrong with your initial reaction, Mr. Brooks! Think of the great-great-grandchildren!!

BOB MURPHY: (puzzled, grimaces, shouts for joy) Yeah! Holy smokes! They’re right! Sorry Mr. Brooks, I was totally wrong. It is possible for our generation to impoverish future ones. Wow this is really neat! Let me walk you through a diagrammatic explanation…

DAVID BROOKS: OK now it’s back to being the free-market guys against the Keynesians. I need a tie breaker. What about you, Professor Landsburg? You’ve always struck me as a pro-market guy who’s still a straightshooter.

STEVE LANDSBURG: Krugman has been saying a lot of good stuff on this. I’m sorry Mr. Brooks, but if you ask me what I think of your fears about a debt “burden” I have to tell you that I think they are idiotic. My only quibble with Krugman is that he’s wrong to focus on whether the government bonds are held by Eddy, Frank, etc. Even if the government in period 9 had to ship apples over to a different Excel table, our descendants wouldn’t be burdened by the IOUs floating around at that time. They would essentially be apples they owed to themselves.

DAVID BROOKS: Well that last line makes absolutely no sense to me, but I know you academics like to be deliberately provocative. But OK, you side with Krugman. So you’re saying that these other guys are wrong?

STEVE LANDSBURG: Look, you’re putting me in an awkward position. I’m friends with those guys. But yeah, I mean Boudreaux likes to go read verbal stuff, instead of thinking it through with precise models, and Nick Rowe is a Canadian, so there ya go.

DAVID BROOKS: And this Murphy character?

STEVE LANDSBURG: He’s a nice guy.

DAVID BROOKS: But when it comes to his dispute with Krugman on whether the government debt can be a burden on future generations, do you think Murphy is making intelligent points?

STEVE LANDSBURG: (pause) Bob makes really funny videos.

DAVID BROOKS: Well, I guess that does it. Go ahead, Mr. Politician, let ‘er rip! A round of 3 apples, for all the old timers! And 100% interest income, for all the young people!

CROWD: Woo hoo! Yeah!

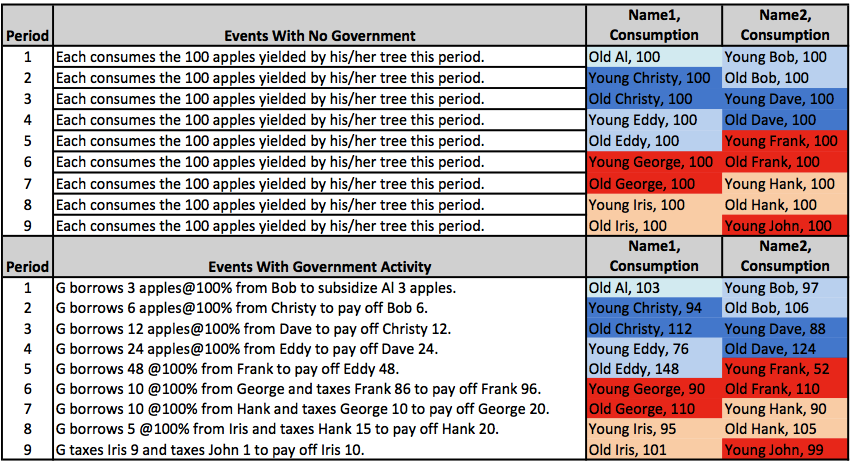

After the decision to give the Old Als 3 apples as a transfer payment, paid for by running a government deficit, events unfold in the following manner:

DAVID BROOKS: (stunned) What the–what the heck just happened?!

BOB MURPHY: Perhaps I can be of assistance. First of all, remember that all of us have the same utility function of U=sqrt(A1)+sqrt(A2). If we had all just consumed our endowments, we would all have 20 utils during our lifetimes (square root of 100 plus square root of 100), with the exception of Old Al and Young John who would only have utility of 10 because they live only one period. Now if you check the math, you can see that Al, Bob, Christy, Dave, and Eddy all have more than 20 utils with their actual consumption patterns, while Frank, George, Hank, Iris, and John all have fewer than 20 utils with their actual consumption patterns. Just like Boudreaux, Rowe, and I were saying, government deficits allow the earlier generations to benefit at the expense of subsequent generations.

DAVID BROOKS: (turns to Landsburg, furious) You lied to me!!

LANDSBURG: What the heck are you talking about? Dude, you need to calm down. Try having some more sex, we’ll all thank you for it.

DAVID BROOKS: You told me our debt wouldn’t impose a burden on our descendants. You told me to trust Krugman!

LANDSBURG: Right, the debt didn’t impose a burden. In fact, it helped our descendants.

DAVID BROOKS: What the heck are you talking about?!!?!

LANDSBURG: You’re even thicker than I thought. Check the numbers. Look, take period 7, where Young Hank lends 10 apples to the government. You’re getting hung up on the fact that with his consumption stream of (90, 105), Hank now only gets 19.7 utils over his life, as opposed to the endowment 20. So you’re blaming his loss of welfare on the debt. But no, his reduction in utility is stemming from the tax the government levies on him in period 8. Suppose Hank didn’t engage in a bond deal with the government, and instead just consumed his after-tax endowment each period. He would then consume (100, 85), yielding utility of 19.2. So contrary to your silly assertion, government debt makes Hank better off. It’s the tax that hurt him. Duh.

DAVID BROOKS: But the reason Hank is being taxed in period 8 is to service the government debt!! The government in our Excel table doesn’t tax for any other reason except to service/retire the debt that our generation initially created by giving a transfer to Old Al. So the debt causes the taxes levied on future generations!

LANDSBURG: Whoa, whoa, whoa. I can tolerate a lot of things, but I won’t stand idly by while someone impugns debt finance. You better take that back, mister. Debt didn’t force the government to levy taxes on those people. Rather, it was the fact that the first five people wanted to all increase their utils. Since we started out in a Pareto optimal allocation of apple consumption paths, obviously when Old Al and Young Bob both improved their lifetime utilities, you had to know people down the road were going to take the hit. Haven’t you ever heard the expression, “There ain’t no such thing as free applesauce”?

DAVID BROOKS: (lip quivering) But…but…Krugman and all those guys led me to believe that it wouldn’t hurt our descendants!

LANDSBURG: You didn’t think levying taxes on people in the future would hurt them? And you call yourself a pundit?

DAVID BROOKS: Well I knew it would hurt some of our great-grandkids, but I thought the government would just take apples from one great-grandkid and give them to another.

LANDSBURG: Right, it did. Don’t you understand how our world works?

DAVID BROOKS: But I mean, I thought it would be a wash, as far as our great-grandkids collectively were concerned. I mean, Yglesias’ thing about the government defaulting, and it just being a wash…

LANDSBURG: Right, it would be a wash if the government had defaulted, say, in period 6. That act would hurt some people but help others, but wouldn’t make society richer or poorer on net.

DAVID BROOKS: Agghh! I’m going crazy here! So how did we end up making Frank through John worse off?! If we had defaulted, and you’re saying it’s a wash…?

LANDSBURG: Oh, I see what’s tripping you up. If the government had defaulted in period 6, it would have been a wash relative to the new scenario where Frank through John already had less utility. Once Al through Eddy had lived and died, and had each achieved more utility than 20, it was obvious that somebody from Frank through John would take a hit. But government tax and bond payment policies could redistribute the hit. For example, if the government had defaulted in period 6 and then levied no taxes, then Frank alone would have taken the full hit. Al through Eddy would have benefited, Frank would have gotten crushed, and George through John would have been unaffected (each consuming 100 apples per period). So Yglesias was right, defaulting on the government’s debt in a particular period can’t make society richer–if it did, then we’d all make side deals with each other and default! Duh. Seriously, you call yourself a pundit?

DAVID BROOKS: (tears welling up in his eyes) But…but…all the stuff about “apple output in any future period is always 200″… If the government takes an apple from one person, it can only give it to someone else…

LANDSBURG: Right, that’s all true. Why is this so hard for you? Look: You guys wanted to give Old Al 3 apples. Somebody had to get taxed to pay for it. You could have taxed the Young Bobs, but chose not to. Instead, you taxed Frank through John, and then the bond market brought that revenue forward (after discounting of course) by getting loans from young people. It’s not the debt per se that made your descendants poorer, it was the government’s decision to tax them instead of taxing the Young Bobs.

DAVID BROOKS: But all of that stuff they were saying about not shipping apples to other Excel tables…

LANDSBURG: Hey! I told you upfront that that was silly. But other than that non sequitur, everything else those Keynesians told you was perfectly true.

DAVID BROOKS: Well, right, now that you mention it, I do remember you saying that their focus on keeping the apples within the Excel table–in the hands of our descendants–was irrelevant. But it’s not like it was a casual aside of their case; they based their whole argument on that “insight” which you said was wrong. And by making me focus on physical apples, they convinced me that it was literally impossible for us to enrich ourselves at the expense of people in, say, period 9, because we only had 200 apples today, and no matter what, Iris and John were going to split up 200 apples then.

LANDSBURG: Hang on a second. Do you honestly mean to tell me you weren’t aware of how debt financing and overlapping generations work? You haven’t read Samuelson’s paper on Social Security?! And now you’re mad at Krugman and me, for not pointing this out to you before? Gee whiz, do you want us to lay your clothes out too in the mornings? You’re dumber than I thought. Maybe you shouldn’t be having more sex.

DAVID BROOKS: (hanging head in shame, cannot withstand Landsburg’s withering criticism any longer and turns to another, inebriated economist) What do you think?

GENE CALLAHAN: Yeah, Steve is right, and Murphy has just been saying one goofy thing after another. Look, we could have achieved the same outcome in terms of everybody’s utils, without using deficit finance at all. Instead, the government could have taxed Young Bobs 3 apples in period 1, then it could have taxed the Young Christys 6 apples in period 2, and so on. So none of this debate was really about whether we could impoverish our great-grandkids; of course we can! The issue has always been, is the debt the thing to blame. What conversation have you been in?

DAVID BROOKS: HUH?!? You’re telling me I missed the whole point of this debate?! The very thing I was worried would happen–that if we didn’t tax the Young Bobs in period 1, but instead paid for the transfer with a deficit, we would foist that burden onto our descendants–is exactly what happened! And I let Dean Baker and all those guys convince me I was stupid!

STEVE LANDSBURG: (aside) You are.

DAVID BROOKS: (turns to a grad student) OK, maybe a younger guy can help me out here. My head is spinning at this point.

DANIEL KUEHN: Well, I’m not really sure why you were surprised by the outcome. Didn’t Krugman let you know that this could happen? I mean, when he said “talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay apples to other children,” how could that not have tipped you off that the above scenario was possible?

This is the cost and the benefit that Murphy was talking about – costs and benefits on individual children, if you add up their whole lifetime income. But within each period you don’t have a transfer of resources.

Isn’t this the Krugman position? Winners and losers but no additional burden on any particular future time period? If you look at future income levels, that remains unchanged. If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”.

DAVID BROOKS: (entire body is now shaking) How in the world are you describing what just happened?! Looking at the individuals from period 6 onward, it’s not true that “obviously some of them win and some of them lose.” THEY ALL LOST. Every single person who lived from period 6 onward was worse off, because of what we set in motion in period 1. No matter what those poor saps did, we and the next few generations had ensured that they collectively were going to be poorer than if we had just paid for Old Bob’s apples with a tax. And the way the government decided to handle this collective burden, in practice it wasn’t just that some of our descendants (like George and Iris) were worse off, but that others (like Hank and John) counterbalanced it by being better off. No, they were ALL hurt in this scenario. And yet Krugman et al. had convinced me that such an outcome was physically impossible.

DANIEL KUEHN: Ah, the problem here is that you’re mixing up terminology. Krugman has established, quite correctly, that the government in our world could make specific individuals in the future poorer, but not that it could make the country as a whole poorer in the future.

DAVID BROOKS: (pauses for several moments, as saliva begins to hang from his lower lip) Daniel, the country as a whole was poorer from periods 6 through 9.

DANIEL KUEHN: (sighs) No it wasn’t. What was national income in period 6?

DAVID BROOKS: Huh?

DANIEL KUEHN: In terms of apples, what was the sum of everybody’s income in period 6?

DAVID BROOKS: 200.

DANIEL KUEHN: Right. And if you guys in period 1 hadn’t started your deficit scheme, what would national income have been in period 6?

DAVID BROOKS: (reluctantly) 200.

DANIEL KUEHN: Uh-huh. See what I mean? Krugman et al. were totally right–you guys in Period 1 didn’t make the nation poorer in period 6 or 7 or whatever. That’s physically impossible; national income in every period is always 200 apples.

DAVID BROOKS: But…but…even so, every single person from period 6 onward was made poorer by this whole thing.

DANIEL KUEHN: Yep, just like Krugman told you could happen.

DAVID BROOKS: (beginning to sob) No he didn’t Daniel… I, I, I don’t even understand what is happening at this point. I need to sit down. (sits in chair)

DANIEL KUEHN: There, there. The problem is, you keep switching in mid-argument between “the nation” and “people in the nation.” Sure, specific descendants at any future date could have been hurt by you guys in period 1, but not your descendants considered as a collective.

DAVID BROOKS: So, just to be clear: You agree with me that Krugman and the other Keynesians were telling me that the nation as a whole couldn’t be made poorer in periods 6 through 9. You agree with me, that they said that was impossible?

DANIEL KUEHN: Yep.

DAVID BROOKS: (breathes a sigh of relief) OK, good, because Landsburg really had me doubting my sanity there for a moment. So–and I realize I have to do this in baby steps because this stuff is so hard for me to get–you agree with me, that Krugman misled me by claiming that the nation as a whole couldn’t be made poorer in periods 6 through 9.

DANIEL KUEHN: No! What the heck is wrong with you? Krugman is right! The nation can’t be made poorer in periods 6 through 9!! National income is 200 apples, with or without debt. C’mon man, I’ve got a wife to entertain. I can’t be here all day.

DAVID BROOKS: (resumes sobbing) But Daniel, how can it be that Frank, George, Hank, Iris, and John were all made poorer? I just can’t understand how all this is possible. (blows nose)

DANIEL KUEHN: I told you before: You’re confusing the nation with the individuals making up the nation.

DAVID BROOKS: So when Krugman convinced me that it was physically impossible to make the “nation as a whole” poorer from periods 6 through 9, I was wrong to infer that it was physically impossible to make every single member of the nation poorer from periods 6 through 9?

DANIEL KUEHN: (shocked) Yeah, what the heck would make you infer that? When Krugman told you that the “nation as a whole” would have the same income from periods 6 through 9, you didn’t realize that this outcome was consistent with “every single person alive” in periods 6 through 9 being poorer? You honestly thought “the nation as a whole in period 6” was the same thing as “every person alive in period 6”? Boy Landsburg called it–you’re not too quick on the uptake, are you?

David Brooks throws a noose around a ceiling rafter. Then he stands on the chair.

DANIEL KUEHN: Hey! Get down from there. This is subtle stuff. Don’t be so hard on yourself.

DAVID BROOKS: (relents and steps down from chair) Yeah, I guess you’re right. I mean, if smart guys like Nick Rowe and Murphy could disagree with Krugman on this stuff, I shouldn’t be disappointed that I kept getting confused.

DANIEL KUEHN: Huh? What disagreement? Krugman, Rowe, and Murphy have all been saying the same thing all along.

DAVID BROOKS: (screaming) Aggggghhhhhhhh!!!!

Scene ends with Brooks in a straitjacket, being loaded into an ambulance while muttering about economists and apples. Ambulance driver turns and says to Brooks, “Sounds like a confusing story. Hey, wanna see something reeeaaaally confusing…?”

Screen shifts to a sharp man with a cigarette. He begins to speak. “Picture a world, where people only eat apples. A man consults alleged experts on government deficits, and is taken on a journey that ultimately shatters his mind–a journey that ends, in the Economist Zone.”

Spooky theme music begins playing as screen fades out.

Interview With the Director

When I first wrote the above, it was mostly intended to be humorous. However, even the act of writing it has shed new insights for me on this fiendishly subtle controversy.

Let me just say that what has happened here isn’t that “these guys were right” or “these guys were wrong.” The amazing thing is that–if we forgive people for slips of the tongue and missteps that don’t hurt their overall position–every viewpoint I’ve incorporated above, had a germ of validity. And yet, as I tried to show with the exasperated “David Brooks,” it seemed that these economists were contradicting each other.

If I were still a college professor, I would honestly invent a course just to have an excuse to play with that OLG model for hours on end, introducing more features like investment in future trees, altruism between generations, private bond markets, etc. I am still in slight shock from the possibilities that this debate has brought to my attention.

Let me close with one observation, just to make sure all of you understand why I think this is such a big deal: Krugman et al. can correctly argue that today’s deficit financing can’t reduce the sum of individual incomes earned in the years 2013, 2014, 2015…until the end of time, subject to all the caveats about incentive effects and so forth. And yet, James Buchanan et al. can correctly argue that today’s deficit financing can reduce the (after-tax) incomes earned by every individual who is alive in the years 2013, 2014, 2015…until the end of time. At first glance it seems that one of these camps must be wrong, but actually they are both right. But because those statements appear to be contradictory, people on both sides have been quite sure that the other guys were idiots or liars.

UPDATE: I just double checked my intuition on something, and yep it works. So let me report it, since it really helps in tying all of this together and getting a handle on what the #%)(#)($* happened in the numerical example above. Recall that I have Steve Landsburg in the script saying that the government in period 1 is giving Old Al 3 apples, and that it could have either taxed Young Bob at the time, or taxed future people. Now the thing is, the interest rate on government bonds in this world is 100%. So if the government wants to tax somebody 86 apples in period 6, for example, then in period 1 that future tax revenue only has a present-discounted value of about 2.69 apples. (That’s 86*(1/2)^5.) If you go through and calculate the PDV of the future tax levies from the perspective of period 1–discounting by 100% per time period–you will see that the future levies add up exactly to 3 apples. So the words I put in Landsburg’s mouth are totally correct, and that’s a very useful way to think about it, in my opinion. The overlapping generations and bond markets allow the present generation to fund transfer payments out of taxes that won’t be imposed for hundreds of years!

This post was a little Major_Freedom-ish in length.

However, I agree with you now. Some generation henceforth will get screwed by piling up debt. Krugman, et al. are only right under the condition that the interest rate does not exceed the growth rate. Their view is effectively a ponzi scheme.

“This post was a little Major_Freedom-ish in length.”

I was wondering why I liked it so much.

LOL, I like you Brian, you’re cool.

Seems I have a signature. Want to here a long story about what I think about that? Yeah, me neither.

This is really awesome.

I’m not sure everyone gets what I’ve been saying, but it’s quite obvious from this that you do. That’ll do, I suppose.

Your last paragraph is exactly right, I think – and Nick made a very important contribution very early on to distinguish all those contributions and say that all of them had something to say. I do wish he gave Abba Lerner more credit in that initial post. After all – the “we owe it to ourselves” dynamic is exactly how we push those costs on individuals into the future (a la Buchanan). The only way we can do that with debt is be creating benefits for others.

That is not a trivial point. The man on the street sees the national debt as only a liability. It’s not only a liability. And the Buchanan point simply can’t be made without the generation of these assets – the point that Lerner, Krugman, and Baker are trying to draw attention too.

So your last paragraph here and Nick’s post are very important – there’s a lot to take in and a lot of important contributions to this discussion.

“The man on the street sees the national debt as only a liability.”

Bologna. They know the debt is funding the fat retirement of government workers, retiring, e.g. in California, at age 50.

And they know the money would otherwise be spent by them on their own families.

Right… that’s part of what the funds raised are spent on (they’re also spent on a lot of other things voters want).

But I think you’re missing the wider point of what I mean by “debt is an asset”, Greg

I don’t miss the point.

And part of the Keynes/Krugman fallacy is the fallacy that we can total up expenditures on investment goods in a pile of “K” and we don’t have to look at what is produced.

When the government “invests” in “green” production facilities which produce goods which are not-economically viable, and production must be halted, production goods must be disposed of, and the factory and machinary which has been built must be decommisssioned or dumped, what you are talking about is economic destruction, not economic production.

Billions spent on a bullet trains from on tiny town to another tiny town in central California is counted as an increase in the size of “K” according to Keynesian/Krugman accounting rules.

According to the economic way of thinking, the production of goods is not the production of value.

But Keynes and Krugman have regressed to a Ricardian / substance theory of value, where increases in the stock “K” based on what has been shifted t into “K” from a stock of goods given a “given” value the past is accounted as an increase in value.

Sorry Greg – I’d respond if I knew what the hell you’re talking about. Now you’re just inventing things about people.

Aggregation misses very important details, whether it is the “capital stock black box” of the Knightian and Chicago viewpoint or the Keynesian GDP aggregates.

Great post indeed. I think there is not much more to be said.

There is only one thing I don’t understand and if you have the time I would appreciete if some of you guys could explain it. Why doesn’t it matter whether the debt is held internally or externally. One oberservation was “The nation can’t be made poorer in periods 6 through 9!! National income is 200 apples, with or without debt.”

To me it seems that this is only true if the bonds are held internally. Am I wrong? I read Landsburg’s post but I just don’t get it. Help me out here!

Who said it didn’t matter whether it was internal or external? I thought it was generally agreed that external debt did matter.

Christopher I’m not totally sure myself. But for example, it is still true that even if the government in period 7 owed outsiders 50 apples as a bond payment, the national income in period 7 would still be 200 apples. Your income doesn’t change because you owe money to somebody, but your consumption could.

However, I don’t know if that’s the whole resolution of it or not. You would certainly think that if the government in period 1 paid Old Al 3 apples that it borrowed from abroad, so that Young Bob didn’t need to reduce period 1 consumption, then the first generation would gain even more, meaning the later ones would have to lose even more.

So yeah, I’m not sure exactly how Landsburg’s “we owe it to ourselves no matter what” point works. I think he is holding everything else fixed, whereas you and I are automatically allowing at least one thing to change because people have more to work with upfront if they borrow from abroad.

Regarding debt held by foreigners, there’s an easy explanation in terms of Nick’s model (which should translate to yours). The burden outcome is no different than the base case where the bonds are held domestically:

Tax Case:

At maturity of the bond, foreigners receive apples in exchange for debt.

Domestic taxpayers pay the apple tax that pays down the bond.

So the domestic taxpayer and generation is down apples.

The domestic taxpayer bears the burden by virtue of being part of the generation alive at the time of the bond pay down, notwithstanding zero involvement with bonds.

And the domestic taxpayer is entirely representative of the relevant (domestic) generational burden, notwithstanding zero involvement with bonds.

No Tax Case:

Then the domestic taxpayer and generation is neutral. He never bought the bonds in the first place, and he doesn’t need any more apples from any source to keep his position square.

So there is no burden.

And the foreigner either sells the bonds to his next generation, or rolls them as in your model. Either way, because he bought the bonds earlier, or rolled them earlier, the foreign sector generation experiences a net neutral apple outcome. Any in any event, the foreign sector internal experience is not defined as part of the relevant (domestic) generational problem.

I’ll refer to Nick’s model again, because I’m not entirely familiar with your numbers yet (although the model looks fine, excellent, and brilliant, to this observer).

So the basic logic of Nick’s model is that there’s a required asymmetry of generational apple flows at the front and back ends. The key to understanding the difference between the domestic and foreign held bond scenarios is that although the net asymmetry is the same, the gross construction of the net is different.

First, the domestic case:

At the very front end of Nick’s model, the asymmetry results from the fact that the first cohort exchanges bonds for apples with the second cohort. The actual up front bond issue itself has no net apple effect, because apples paid for bonds are also distributed back as a transfer.

At the very back end of Nick’s model, the asymmetry results from the fact that the final cohort (the one that is taxed) exchanged apples for bonds with the penultimate cohort. The actual bond maturity cum tax itself has no net apple effect, because apples paid for taxes are used to pay down the bond.

Intermediate cohorts who buy or roll bonds at the beginning of their periods must buy or roll them prior to death, in order to “hedge” their lifetime apple positions back to square, in respect of government debt effects.

(My sense is that Krugman, in believing in the “we owe it to ourselves” meme as a generalization, has missed the point about the sporadic appearance of asymmetry.)

Now, the foreign case:

At the very front end of Nick’s model, the asymmetry has nothing to do with bonds. It is entirely due to the distribution of apples as a transfer. Compared to the domestic case, the asymmetry is the result of one half of the upfront government transaction (the transfer but not the bond issue), rather than the selling of bonds at the end (the domestic source of asymmetry). The other half of the government transaction (the bond issue), combined with the selling of the bonds at the end, has a net neutral apple effect on the foreign sector and doesn’t even touch the domestic sector. So the resulting net asymmetry is the same as the domestic case, but comes about in a different way.

Finally, a similar variation occurs at the back end of Nick’s model in the foreign case. The domestic sector generation is not involved in the bonds at all. But it ends up net down apples because it must pay the tax. It’s the same asymmetry as the domestic case, but a different way of getting there.

The full case, domestic and foreign, is laid out here:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/01/the-30-years-debt-burden-non-war.html?cid=6a00d83451688169e20162fef52c26970d#comment-6a00d83451688169e20162fef52c26970d

Debt is always held internally (i.e. in the respective country’s banking system), but possibly by people/institutions who reside abroad and/or who hold foreign passports. The proceeds of the debt (interest payments and eventually, upon maturity, principle) can also only be spent internally. You cannot spend Swiss Francs in China. The only important question is: will they be spent at all? And, if so, what will they be spent on? The debt itself, on the other hand, is innocuous.

It’s weird how this whole storm in a tea-pot totally misses the one truly salient point re. Govt debt- viz

1) Agency Hazard- if Govt’s aren’t utterly faithful agents of their principal- the taxpayers- Landsburg’s argument falls immediately.

2) With Rational Expectations, no Uncertainty, zero transaction costs- the Govt is always a single instantaneously fulfilled market transaction away from zero debt because it can sell its future revenue streams. What makes Govt debt, like any other debt, interesting is if it higher or lower than anticipated- i.e. some risk or information was overlooked. In this case, debt does mean the same thing for the nation, the company’s shareholder, and the individual agent- viz. cut back on entitlements and, so to speak, have a call up of partly paid shares. There is no fallacy of composition here and no need for OLG modelling.

3) Ricardian Equivalence is built on assumptions which allow agents with Rational Expectations- applying if need be a Shutzian ideal-type Rational Choice hermeneutics- such as to evolve the ‘Verstehen’ (or common sense!) to form coalitions which internally agree to neutralize uncertainty arising from Govt transfer/tax policies. Assume universal risk aversion and such a coalition- which essentially boycotts the Govt bond market and undoes any transfers it otherwise effects- will come to dominate by compensating people not to deal with the Govt or applying a sanction of some sort.

4) Public finance is a very valuable piece of Social Capital. Debauching it might be the very worst thing we can do.

Landsburg says ‘The greatest damage one generation can inflict on the next is to consume everything in sight, and this is always possible without deficit finance.’

This is not true. Deficit finance can lead to hyperinflation, the collapse of the market for Govt bonds, collapse of confidence in the regime, the rise of extremist political parties, War, Genocide, Slavery.

Lansburg thinks the only way we can fuck up our grand-kids is if we eat up all the non renewable resources and let all capital goods depreciate away to nothingness. But, countries which have been invaded and denuded of all productive capacity and natural resources can still bounce back if they inherit Institutions with a reputation for, or even new found dedication to, thrift, transparency, zero agency hazard etc.

Indeed, under plausible assumptions and assuming factor mobility, they may well stand taller than the rest- as happened to West Germany- within a relatively short time.

Epic!

Bob,

If I were still a college professor, I would honestly invent a course just to have an excuse to play with that OLG model for hours on end

I think that course might already exist…

Seriously – that sounds like my macro course at GW, which I thought was something of a waste until now.

That’s not entirely fair – the first half was OLG, the second half was endogenous growth, and I do like the endogenous growth stuff.

vimothy, no you are misunderstanding me. I’m not saying I would be the first to invent a course studying OLG models. I’m saying I would invent a course that would let me play with these models for hours on end, and be “working.” No such course yet exists.

I don’t imagine that’s one the Mises Institute will go for, huh?

I thought

“I’m saying I would invent a course that would let me play with these models for hours on end, and be “working.”

was what it was all about at the LvMI. I mean just look at how much fun they’re having.

True – I’m just not sure they’d go for such a mainstream neoclassical method as OLG.

However, Bob’s quite good at translating this stuff into Austrian economics. If anyone could pull it off, he could.

You could be his devil’s advocate TA.

Bob, Got ya.

Maybe you can get the govt borrow some money, then use it pay you to teach youself a course on macro.

After all, in the future, since assets = liabilities, the debt will be a wash and no one is any the worse off. And since you are strictly better off, this is a Pareto improvement.

In fact, I expect Krugman and Baker will want to write a couple of op-eds demanding that it be made to happen.

“Krugman et al. can correctly argue that today’s deficit financing can’t reduce the sum of individual incomes earned in the years 2013, 2014, 2015…until the end of time, subject to all the caveats about incentive effects and so forth. And yet, James Buchanan et al. can correctly argue that today’s deficit financing can reduce the (after-tax) incomes earned by every individual who is alive in the years 2013, 2014, 2015…until the end of time.”

The fact that “individual incomes” means “individual nominal incomes”, I think is enough to say Krugman et al are making a moot point.

After all, the purchasing power of nominal incomes isn’t fixed, so who cares if people are making equal collective nominal incomes relative to some counterfactual world that while having the same nominal incomes, it has higher real incomes because people lent to an entity that produces and earns money to pay back its debt (thus increasing purchasing power of money) instead, as opposed to an entity that has to force a game of nominal income redistribution and net asset destruction on others in order to make good on their debt?

If the government just printed money to pay back all its debt instead of taxing people, Krugman would probably say

“We can do better than only “a wash” for future generations. We could increase the sum of individual incomes! So not only would there be no net loss to our future generations, there would be a net gain to future generations as well! [Political group I want to refute] can never win, because even if they succeed in decreasing taxes, I can get my desired increased sum of individual incomes another way, by “reluctantly” supporting central bank policy, i.e. inflation.”

Since apples are being used for both consumption and “payment”, and so the difference between consumer goods production on the one hand, and money production on the other, becomes harder to disentangle.

MF wrote:

The fact that “individual incomes” means “individual nominal incomes”, I think is enough to say Krugman et al are making a moot point

No, Major Freedom, that’s why I’m spending some much time with this simplistic apple world. We are talking about real income; we’re counting how many apples are produced.

This isn’t a nominal/real thing. It’s a “adding up the real incomes earned in 2012 by everybody alive” versus “adding up the real incomes earned by everybody who is alive in 2012.” At first glance those seem interchangeable, but they’re not. The only thing that is hilarious to me is that Daniel Kuehn was shocked that people are missing that distinction.

No, Major Freedom, that’s why I’m spending some much time with this simplistic apple world. We are talking about real income; we’re counting how many apples are produced.

Are you sure Krugman wasn’t talking about nominal incomes when he said “we owe it to ourselves”? Isn’t the “it” the money being taxed and being given to bondholders, and not pizzas and Toyotas?

You even said way before that the debt “burden” was the taxation, which is money, and not the fact that you have fewer pizzas and Toyotas.

Maybe since you used apples in your example, and abstracted away from money, we lost an important aspect of Krugman’s argument?

“This isn’t a nominal/real thing. It’s a “adding up the real incomes earned in 2012 by everybody alive” versus “adding up the real incomes earned by everybody who is alive in 2012.” At first glance those seem interchangeable, but they’re not. The only thing that is hilarious to me is that Daniel Kuehn was shocked that people are missing that distinction.”

I mean, Krugman said in his original post about “we owe it to ourselves” here:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/12/28/debt-is-mostly-money-we-owe-to-ourselves/

That

“What you can see here is that there has been a big rise in debt, with a much smaller move into net debtor status for America as a whole; for the most part, the extra debt is money we owe to ourselves.”

and then

“People think of debt’s role in the economy as if it were the same as what debt means for an individual: there’s a lot of money you have to pay to someone else. But that’s all wrong; the debt we create is basically money we owe to ourselves, and the burden it imposes does not involve a real transfer of resources.”

and then

“That’s not to say that high debt can’t cause problems — it certainly can. But these are problems of distribution and incentives, not the burden of debt as is commonly understood. And as Dean says, talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children, which is a very different kettle of fish.”

He is saying that what is “owed to ourselves” is the money, not the real goods, i.e. real income.

I love your OLG models and everything, but Krugman was in fact talking about total nominal incomes, not real incomes.

Just to throw this out there, maybe this means we have to take Krugman’s statements and approach them in a whole new way.

Maybe we should grant that Krugman is right as far as money goes, both cross sectionally and generationally over time, but then say that because more government borrowing and spending in money reduces economic productivity in real terms, on the basis that it sacrifices private lending and investment according to profit and loss, for the “benefit” of more government spending, which means total production must decline (imagine the government borrowing from the entire pool of the market’s savings and then spending it to get a clearer picture), and when total production declines due to government borrowing, we leave less real capital wealth for our children to utilize for their production and consumption needs. Sort of like eating the seed corn.

Nominally speaking, it can be a wash for future generations, or it can be a loss, or it can be a gain, depending on total nominal spending and incomes.

In real terms however, our children lose on net no matter what, no matter how much money is printed, taxed, borrowed, spent, or transferred by government (remember that guys? Austrians? Anyone?), because there is less capital invested according to profit and loss calculations than otherwise would have existed.

So maybe the problem with government debt is that it forever eliminates the alternative world possibility of that loan money going to some more productive use, like lending to a producer who does not tax or print money to backstop its debt obligations.

re: “The only thing that is hilarious to me is that Daniel Kuehn was shocked that people are missing that distinction.”

No that’s not shocking to me. It’s precisely because it’s so easy to confuse the points that I think things like Krugman’s Op-Ed are so important to put out there.

Legen … wait for it … dary!

I already had an idea of how you may solve this but was not sure. I mean I saw in your earlier example that if G had taxed Iris and John in period 9 each 50 apples then both were worse off, you might stretch this over several generations.. Anyway this shows that if the debt needs to be paid off because the debt level is too high all might suffer over several time periods and the reason this is possible is because generations are necessarily overlapping… The problematic issue due to the democratic process that allows for this borrowing in the first place gets even bigger..

The only question that remains is how an economist then can fault the man on the street for saying: “Debt will burden future generations” ? It’s like faulting someone for saying “Holding a finger within candle’s fire will burn it” with “No that’s wrong. It doesn’t harm your toe.”…

skylien thanks. Right, I go back to my original analogy where the layman says, “That guy killed people with a gun!” and Landsburg says, “You idiot, he did it with bullets. People need to stop thinking guns can be deadly weapons, they obviously can’t. Guns are neither necessary nor sufficient for hurting people.”

Maybe that’s the reason that most Libertarians are opposed to Anti-Gun Laws 😉

I just wanted to join in the singing high praises for you Dr. Murphy.

This post shows you at your best as an economist, comedian and playwright.

Gene Callahan is [not the smartest guy in my opinion.–Edited by RPM]

Real slick, Bob. LOL

If I may attempt to summarize what we have learned:

Time periods do not overlap, but generations do. Therefore, while it is NOT possible to transfer wealth between time periods, it IS possible to transfer wealth between generations. For that reason, earlier generations CAN impoverish later ones.

The End

True.

But we experience life in time periods, in relation to other people in that same time period.

That seems significant too, don’t you think?

That doesn’t mean “don’t worry about who gets hurt by debt”. Nobody has said “don’t worry about who gets hurt by debt”. So we should stop pretending anyone has said that.

I would say not as significant as you probably think.

After all, wealth production, exchange, and income are all temporal concepts. They necessarily take place over time, sometimes, perhaps oftentimes, decades or more for the total production cycle to take place.

Because of that fact alone, we cannot possibly abstract away from the “earlier generations CAN impoverish later ones” context, in order to focus on the “but we experience life in time periods, in relation to other people in that same time period” context.

It would be like claiming you can abstract away from time in order to explain how the economy works. Oops, isn’t that what Keynesians do? [Ducks and runs away quickly before being pelted with eggs].

re: “Because of that fact alone, we cannot possibly abstract away from the “earlier generations CAN impoverish later ones” context, in order to focus on the “but we experience life in time periods, in relation to other people in that same time period” context.”

Right.

Nobody is asking you to abstract away from that.

What is the significance then of “But we experience life in time periods, in relation to other people in that same time period” that ““earlier generations CAN impoverish later ones” cannot explain, or does not explain well, or masks/hides?

Earlier generations can impoverish later ones through debt obviously doesn’t carry with it the implication that earlier periods can’t impoverish later periods through debt (although the OLG model here can show BOTH points).

My point, Major Freedom, is that one does not have to abandon the first point to make the second.

Why would one want to abandon the first point to make the second point?

You act as if we have to choose between the conclusions.

We don’t. Both are right.

This time, THIS TIME, I am actually very laid back, so my questions aren’t rhetorical / agenda driven / jabs, you know how like they usually are.

“Earlier generations can impoverish later ones through debt obviously doesn’t carry with it the implication that earlier periods can’t impoverish later periods through debt (although the OLG model here can show BOTH points).”

I hope you can understand why I asked what I asked, if I were to next respond and say that I don’t see how “periods” can be impoverished that is apart from people, and hence “generations” by implication, being impoverished. I mean, the two stage generation model Murphy laid out was, I think, to separate young non-tax-paying people, and old tax-paying people, or young tax-paying people, and old non-tax-paying people.

I’m seriously really trying to disentangle the differences between periods and generations, because I’m one of those morons who is having trouble differentiating between the two.

I mean in my mind I can’t even conceive how cross sectional time periods, APART from generations would work. Yes, I know the given argument, which is that generational differences are between young and old, and time period differences are cross sectional slices over time, but I just can’t think how the latter can make sense by anything other than through the generational understanding.

I mean, even for an individual, when you think of them, you must think of them over time, and when you do that, you’re immediately taking into account an older version of them, and the current, newer version of them.

The OLG model is simplified, so it can’t elucidate the fact that when we say “new generations are burdened by previous generations”, all we are really saying, in my mind at least, is:

“The future is going to be worse than it otherwise could have been had certain variable(s) in question been different.”

This future can include the person making this statement, or it can exclude them, but all else equal, saying the above statement NOW, the future for everyone is going to be worse than it otherwise could have been had we did things differently.”

Maybe economics can allow us to say that a person “voluntarily” lending money to the government is a priori worse off, FOR THEM and for EVERYONE ELSE, because they have just encouraged/obligated a violent agency to unleash indiscriminate confiscation of wealth which can include the person who originally lent to it, and if not the person who lent to it, then certainly others.

Suppose I just take $100 from you. Is it really possible for me to say that I gained and you lost, and that there is no “collective” loss or gain? I would say there IS a collective loss. I would say that I lost and that you lost. You lost because I took your money. I lost because I lost what I could have traded with you had you been able to utilize that $100 for yourself, improving yourself in some way thus making you stand in a better trading position vis a vis myself. I mean, imagine if you were starving, and that $100 was your only meal ticket. If I took that money from you, I potentially sacrifice a lifetime of internet squabbles.

So back to your point then, I don’t see how in one “time period”, which is supposed to be a zero time cross sectional abstraction from reality that always moves forward, it is possible that wealth redistribution can ever lead to a net zero “collective” loss. I think the mere presence of the violent redistribution generates losses for everyone, including those who gain what others have lost.

What people miss, I think, is that even though some gained what others have lost cross sectionally, those who gained actually incurred a loss of what they otherwise could have gotten from others had they not been sacrificed but approached peacefully.

I think that’s why humans decided to engage in peaceful productive activity in the first place. If no gains could be made in this way, compared to straight up redistribution like the lower animals, we would have never started to do it.

So maybe we’re missing a huge elephant in the middle of the room by saying there is no net loss to everyone in a world where some people are robbed to pay others. Maybe everyone loses, we just can’t see it because it’s a counterfactual, so we instead get sucked into focusing only on the OBSERVABLE “gain” and “loss”, and believe it can only be a wash collectively.

The more I think about this, the more I doubt the entire premises Krugman you and you are depending on when you make your arguments. I just seems like you’re ignoring the benefits of free trade for all people, and how reducing free trade incurs an unobservable cost on everyone, that can ONLY be understood.

“…earlier periods can’t impoverish later periods through debt…”

It is true that, in a simple consumption-based model, earlier periods can not impoverish later ones.

However, in the real world – where debt can alter the absolute amount, proportion, and direction of investment – earlier periods CAN impoverish later ones.

“True. But we experience life in time periods, in relation to other people in that same time period. That seems significant too, don’t you think?”

Yes, but I think the main point anti-debt people are trying to make is that it’s unethical for one generation to benefit at the expense of another. Talk of time periods has been used to obfuscate rather than shed light on this fundamental issue.

Time periods do overlap just as surely as generations do. If you fall for the sleight of hand in trying to ignore this, you will overlook certain aspects of this problem. Instances in time are what don’t overlap.

I have to disagree. Period A (2000 – 2010) and period B (2005 – 2015) do not exist simultaneously for five years. They SHARE the same five-year period. Real time is singular and does not overlap with itself.

Not sure what we disagree about. A time period is a mental construct. It can be for the past, for the future, or it can contain the instant in time in which it was formed. However, time periods can overlap in a construct, or may not, but if they do not, then they share nothing.

Neat, creative approach, the screenplay, Doc. And it was helpful and enlightening. Thanks for your efforts!

Excellent Bob!

Bob: This made all the hours of lost productivity from reading these collective debt blog posts worth it. Thank you.

Bob: we need a slogan

Economics is about:

“PEOPLE, not GDP!”

maybe.

“PEOPLE, not time periods!”

Dunno.

Mises already beat you guys to it.

“HUMAN action is purposeful behavior.” – pg 1, chapter 1, paragraph 1, sentence 1, “Human Action, A Treatise on Economics.”

“PEOPLE, not GDP!*”

*NGDP is okay though.

Even when unemployment rises and impoverishment rises, NGDP is all that matters, ergo NGDP is the most efficient target. QED.

Take a look at this image of how retirement pay is progressively swallowing almost all of the state of Illinois education budget, as the state begins to fund an ever increasing part of its budget with borrowing / debt:

http://wp.patheos.com.s3.amazonaws.com/blogs/theanchoress/files/2012/01/ILEducationSpendingHigherEduc.jpg

Not to worry! We just owe it to ourselves!

Well, of course! Why should we be drawing distinctions between those drawing benefits and those paying them. They are all Americans, and they are all human beings.

Illinois needs to balance its budget, but then again Illinois is not fiscally sovereign.

Ha, ha! That was great!

I finally understood why there won’t be 0% interest in this particular world, even with no economic growth — because people’s productivity/consumption doesn’t fall when they get old, or for any reason at all. Sorry, I was having a hard time subjectively relating to them. This world is too weird for me to relate to, I suppose. But if, say, old Al was too sick to pick apples, you might have told the other guys that they might want to hold such a bond so that they could redeem it if they ever got sick like he did, and could keep their utils up.

And if every character’s output fell by 1/4 or so in their ‘old’ phase (as with real people), then the bond scheme would have some utility for them and wouldn’t blow up over time due to interest. But you’d still have to tax somebody someday to pay for it….

Anyway, really great! I was just being brain-dead. I think I agree with you now.

Scott: For the people who are never taxed in either period, there has to be positive interest rate in this particular example, because to do something like (99, 101) would make the person worse off. Since there’s diminishing marginal utility in each period (that’s why I used sqrt), if you are going to give up some of your consumption in period1, you need to be offered more than 0% interest to compensate.

Why is there no subsistence lower bound in this economy? Since apples can’t be stored anyone producing more than subsistence is stupid. Your table crashes immediately. Al can lend apples to the Govt to get back them same apples. Otherwise nothing happens in this model.

The insight for you to carry away is that if the Govt tries to achieve a policy objective by using a policy instrument predicated on agents being less rational or having a smaller information set, then even a small perturbation in agents information or intertemporal pref. will lead to a totally unintended consequence such that the policy instrument has to be abandoned.

more apples, like more sex, might be more fun, no?

you are scrooge mcduck then sitting on your millions saved but never consuming extra?

I am sorry, but Krugman making the distinction about external vs internal debt demonstrates that he didn’t really understand what he was writing in the initial blog post, so even if I credit Kuehn for actually understanding this (I don’t- his arguments in defense of Krugman have changed constantly over the last week, too, as Murphy has methodically cornered him).

If you are going to make the argument that the debt is a wash because some apples/money are owed to other people in a future time period, then why draw any distinction at all between national borders? If the debt is a wash, then it must be a wash regardless of where beneficiaries/burden-bearers live, right? It shouldn’t matter that Americans on net might be worse off in the future since the world on net still has the same income (all else being equal), or if it does matter, as Krugman suggested right at the beginning (otherwise, why would he offer it as a caveat?), then making the argument that “we owe it to ourselves” was always a non sequitur that he never expected to get called out on. Seriously, an individual is to a national entity, as the national entity is to the entire world.

What is really good about this last example of Murphy’s is that it clearly shows that it is possible for nearly every single person alive at some point in the future to be made worse off as the burden of the transfers gets recognized and finally liquidated, meaning that beyond that point, future people again become indifferent to what happened in the past.

I’ve only changed one position, and that’s that I’m prepared to give Dean Baker more credit than I did initially (I haven’t come out with this outright because I’m still chewing on it).

Otherwise nothing has changed. As different issues come up I’ve focused on those different issues. And once things got real specific about what costs they were referring to it was clear to see what the disconnect was.

But if you’re going to claim that my defenses have “changed constantly” I’d appreciate it if you produce some evidence. The focus of the argument has changed somewhat with the introduction of the OLG models… that’s about it.

Until I gave up on it yesterday, you kept trying to get me to defend something I’ve never defended. So I’m not quite sure you’ve got the firmest grasp on what my defenses or arguments have been.

Daniel,

You have moved from the position that the the problem in the future is one of distribution of resources to one where the outcome cannot be rectified by redistribution. It was good that Murphy got you to acknowledge that single, important fact. This goes to the heart of what Krugman was trying to imply in that original blog post- that in the case of internally held debt, the “owing it to ourselves” means that the burden is one for the future selves to correct, or not, as they see fit, because it only was a matter of distribution (that is what he meant by “different kettle of fish”).

You wrote the following last week on your own website:

You eventually tried to back out of this position by trying to focus on “Iris” in that example as an individual rather than as a placeholder for a generational cohort in his OLG model. Is or isn’t Iris a future generation in this model, and do you acknowledge, now, that she bears a burden in the future in this same model? Do you acknowledge that Iris cannot ever be made whole in period 9 in the future without making some contemporary, or future person worse off in this same model?

I realize you are trying desperately to group the collective at any point in time as net neutral (this is certainly what Krugman was doing right from the start), but that is an assumption built into Murphy’s and Rowe’s model, and it is illegitimate for you to try to use this assumption as proof that you and Krugman understood and agreed with Murphy all along. You clearly didn’t since you did write that quote I cited above.

Let me try this another way since it has been difficult to get a straight answer out of you- if it really is just net neutral over the entire collective at a point in time, then shouldn’t it be possible to make Iris’s consumption over her lifetime 200 apples without harming any other person? And if you agree that it is not possible (something you did agree to yesterday) then of what matter of importance is the claim that “we just owe it to ourselves”? Everyone before her was happy to overconsume, but are now dead, and everyone after her is going to be indifferent if she and her generation is left holding the bill.

Krugman’s initial statement was a massive non sequitur and is the cause of the blog war the last week. If he really did hold the position that you now claim he did, why did he muck it up so royally? I assert he mucked it up because he didn’t understand what he wrote and why it was wrong.

re: “You wrote the following last week on your own website:

There is no burden on future generations in Bob’s example.

You eventually tried to back out of this position by trying to focus on “Iris” in that example as an individual rather than as a placeholder for a generational cohort in his OLG model.”

I didn’t change my position here – this was when we were sorting out exactly what people meant when they were using the word “future generation”. I no more changed my position than Bob did – we just all agreed to use Bob’s terminology more or less.

I made my point back then conditional on how we were defining things.

re: “I realize you are trying desperately to group the collective at any point in time as net neutral (this is certainly what Krugman was doing right from the start), but that is an assumption built into Murphy’s and Rowe’s model, and it is illegitimate for you to try to use this assumption as proof that you and Krugman understood and agreed with Murphy all along.”

First, there’s nothing “desperate” about what I’ve been doing and I’d appreciate it if you don’t talk about me like that. Second – what I’ve been saying is that the models don’t provide the counterargument to Krugman that they think they do. If they want to actually move away from the assumption of an endowment economy that’s great. I encouraged that too in fact (although I’m not doing all that work personally). But they can’t pretend they’ve contradicted point when they haven’t.

re: “Let me try this another way since it has been difficult to get a straight answer out of you”

I’ve provided nothing but straight answers Yancy. I’m really getting sick of these insinuations from you.

Daniel,

You still didn’t answer the questions. This is why I make the insinuations I have made. Does Iris represent a future generation/s? Can she be made whole without transferring the burden to her contemporaries, or her future generations? If you agree that she cannot be made whole, do you now agree that the debts incurred today, all else being equal, do represent the present and past overconsuming at the expense of future generations?

These aren’t hard questions, Daniel, and yet, when pushed to answer them you consistently fall back to trying to pretend there is great honest debate about what is meant by “future generation”. There really isn’t any debate about that you, yourself, is trying to create by, I now think, by deliberately trying to aggregate future people’s inappropriately.

What you are trying to do would be exactly would be equivalent to someone trying to claim that income disparity in March 2012 is going to be meaningless since, on aggregate, the country’s income is the same whether it is skewed or if everyone had identical incomes. You would surely not agree with that, would you? Yet Krugman was trying to imply something equivalent about debts in the future, internally held.

Bob, thanks for all the commentary on this. It’s been interesting.

I’ve learnt that the method by which one aggregates individuals into groups, and the labels that one attaches to such groups, can have an important influence on a debate’s ability to reach resolution. If people are aggregating differently, and using non-standard words for their categories, then the debate will degenerate into shouting matches.

I’ve also learnt that future cohorts can indeed by made poorer by present cohorts who borrow to finance consumption.

Thanks for the kudos everyone. I don’t want to admit how much time I spent over the weekend getting this ready. (Also, for those who are curious, I had that Excel table already constructed when I made my wager to Daniel Kuehn in an earlier post. But the young whippersnapper didn’t step into it.)

Also, just to be clear, I don’t think Krugman, Baker, and Yglesias realized future generations of people (not time periods) could be made poorer in this fashion. In fact, if they did know that and still wrote their columns/posts the way they did, I would think they were bad guys. But no, since I didn’t think it was possible until reading Nick Rowe’s stuff on this, I am giving them the benefit of the doubt.

I’ve got to confess I’m somewhat confused about the concern with the ordering of the burdened future generations (ie – cohesive sets of individuals who live across multiple periods with other similarly coherent sets of individuals who live across slightly different periods).

I didn’t think about this until your example either – whether after a certain period every generation carries a lifetime burden or not.

My question is – why does this matter? Who cares if the burden comes after a couple generations that benefit or before? Or perhaps the burden and benefit are alternating. What is the significance of this observation? What’s the value added on top of the fact that we know somebody in the future is going to be burdened?

Also – I like the exposition of the Landsburg position here. I hadn’t been paying attention to that front quite as closely (in fact its impressive that you’ve been juggling three or four fronts). That was a good summary. I’m not sure Landsburg’s point is as crazy as “guns don’t kill people – bullets do”. It’s an important point, particularly once you take Samuelson into account and you realize you don’t necessarily have to have any taxes at all (ANOTHER THING that laymen could be reminded of by a gifted NY Times blogger who deserves our support in his public education efforts).

” Who cares if the burden comes after a couple generations that benefit or before?”

Just read the exchange between the crowd and the politician again. It is because those future generations cannot “Boo!” today.

“It is because those future generations cannot “Boo!” today.”

Maybe they can, and that’s what was keeping Keynes up at night.

Hey everybody, I updated the main post with this interesting twist. I had it in the original version implicitly, but I want to make sure you see how cool this is:

UPDATE: I just double checked my intuition on something, and yep it works. So let me report it, since it really helps in tying all of this together and getting a handle on what the #%)(#)($* happened in the numerical example above. Recall that I have Steve Landsburg in the script saying that the government in period 1 is giving Old Al 3 apples, and that it could have either taxed Young Bob at the time, or taxed future people. Now the thing is, the interest rate on government bonds in this world is 100%. So if the government wants to tax somebody 86 apples in period 6, for example, then in period 1 that future tax revenue only has a present-discounted value of about 2.69 apples. (That’s 86*(1/2)^5.) If you go through and calculate the PDV of the future tax levies from the perspective of period 1–discounting by 100% per time period–you will see that the future levies add up exactly to 3 apples. So the words I put in Landsburg’s mouth are totally correct, and that’s a very useful way to think about it, in my opinion. The overlapping generations and bond markets allow the present generation to fund transfer payments out of taxes that won’t be imposed for hundreds of years!