Medium-Term Treasury Yields Rising Quickly

On a conference call today with some people in the financial sector I made sure everyone was aware of this:

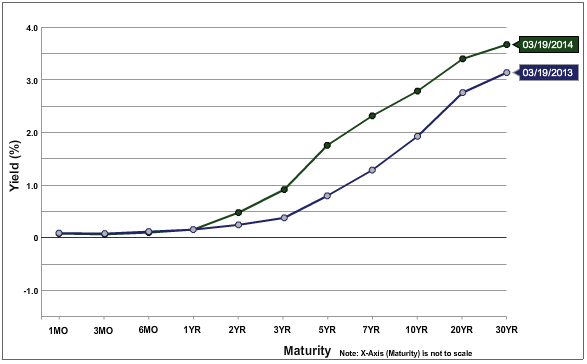

I think a lot of casual observes (i.e. not the bond traders obviously) just think about the fed funds rate, and maybe the really short maturity Treasuries. But as the chart above shows (from here), the yields on 7-year and 10-year Treasuries have risen dramatically in just the last twelve months. In particular, the nominal 7-year yield has risen from 1.23% to 2.31%.

There are lots of ways to explain what’s happened, but be careful–if you go to the link and fiddle around with the settings, you’ll see that back in March 2011 (i.e. three years ago), the yield curve was uniformly above where it is right now.

I realize some of us have been raising alarm bells since the winter of 2008, and that other analysts have accused us of crying wolf, but I really don’t see how this ends well. The Keynesians have lectured guys like me saying, “When nominal interest rates are near zero, bonds and cash are interchangeable, so open market operations don’t have the usual impact on spending and prices.” OK, so what happens if the yield curve keeps shifting up, especially if the increase filters down to the shorter maturities? At some point, the commercial banks are going to resume normal lending, and the Fed will have to either raise the interest rate it pays on excess reserves, or it will have to rapidly reduce its balance sheet. Either way spells trouble.

I can’t even begin to imagine the scope and extent of malinvestments caused by these rates. Everyone in the “Do not let the market correct, and keep rates low / keep spending up” crowd will realize how wrong they were.

Yeah? Is someone like Scott Sumner going to make an about face when he has basically already stated that any collapse is because the Fed has been to tight?

Whatever happens most will crow that it is a sign they were right all along.

That is the nice thing about economics. No matter how different all the opinions are and that at the end there really is only one truth, yet whatever happens all can make a smug face proudly proclaiming that what we see happing is exactly what their theory would say. At worst this or that other factor wasn’t considered enough that actually did offset that real world trend (if you were foolish enough to try to predict one) completely and might have even reversed it into the opposite. However that doesn’t damage the model as a whole, but rather confirms it.

So if you are a loser, I encourage you to become an economist. No matter which side you pick, no one will ever be able to prove you wrong, you will never lose.

According to the logic used in this post, the low rates are leading to less investment since banks won’t lend when the rates are low. He’s claiming the higher rates will lead to higher investment, inflation.

“I can’t even begin to imagine the scope and extent of malinvestments caused by these rates.”

No need to use your imagination.

http://blogs-images.forbes.com/joshbarro/files/2012/04/spending-GDP-chart1.png

The graph shows that over the past 25 years govt spending as a % of GDP has barely grown.

The graph also shows that the WW2 peak is beaten as well.

The statists always have to squirm to save their narrative.

And remember this Austrians……… Government is STILL not at the correct size. One day…….. just maybe, we will reach this mythical level and we will experience the quasi-boom state.

Is that cash account spending, or including contingent liabilities (e.g. pensions, Social Security, etc) ?

No contingent liabilities

I don’t think it’s completely accurate to say yields are rising quickly or just generally in the the past 12 months. You get the impression that yields have been rising consistently month after month in the past year, and it’s a continuing trend. Yields rose dramatically in a period of around 3 months from May to August the relatively stabilized in the past 7 months.

http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/USGG10YR:IND

I still remember Wenzel’s embarrassing post when he was hilariously screaming fire back in 2011 when the 10 year yield was 3.5%.

http://www.economicpolicyjournal.com/2011/02/interest-rate-spike-since-qe2-explained.html

And course the yield ended up falling another 2 percentage points.

I’m sure yields will rise as the economy recovers, but I haven’t found your doomsday fed exit scenarios very convincing.

and then* relatively stabalized

DJ thanks for the context. FWIW, I didn’t have your exact nuances in mind, but that’s why I recommended caution in the OP. Specifically, I was thinking that if the Fed can push down the whole yield curve between 2011 and 2013, then just because the yield curve has drifted up in the last 12 months doesn’t mean the end is near.

Cash at least will keep its nominal value, but if you are holding a 3month bill and the market yield happens to go up, then you can’t sell or exchange what’s in your hand other than at a loss. Three months can be a long time to get stuck with no access to your bank account.

When I saw this I thought of this post at houseofdebt

houseofdebt.org/2014/03/17/fed-meetings-and-asset-prices.html

Adjusted for volatility they found that intermediate government bonds moved significantly more than either short or long bonds in response to taper on/off.

“At some point, the commercial banks are going to resume normal lending, and the Fed will have to either raise the interest rate it pays on excess reserves, or it will have to rapidly reduce its balance sheet. Either way spells trouble.”

Why does this spell trouble rather than being a sign of recovery ?

All 3 of the options in your list in your linked to article would address the issue of “excess” reserves in the system at that time. Option 2 (just reduce the money supply by selling some of the assets back to the market) would be the monetary purists preferred option. I can see that politically-motivated issues around CB paper losses might be an issue and high-jack this policy, but I don’t see nay economic issues with it.

I wonder if Brad DeLong has read this article ?

The US government is running a big deficit every year.

If the Fed starts to sell government bonds at a discount, you can be sure there’s no way government can also sell into such a market. Bad things will happen, and it seems unlikely that Yellen will say “No” to Obama any time soon.

Is there something special about 1 year ago? As far as I know there’s no seasonality in interest rates.

I just looked at something called the 5 year TIPS breakeven rate…now at 1.77 percent, down from 2.23 percent a year ago…the market says even the CPI will be under 2 percent in 2019…let alone the PCE…

In Japan inflation died…it can’t happen here?

http://www.tradingeconomics.com/japan/inflation-cpi

Abe sure got what he asked for. Let’s see if it fixes everything.

I just interviewed three different institutional real estate managers…all three are high on Japan….

Abenomics appears to working…although the third arrow is still in the quiver….

But the BoJ has committed forcefully to higher inflation rates…the Fed is committing to lower inflation rates….

You mean they are set to ride the next wave of asset inflation. Sure, why not make a buck out of other people being slow to react. Will that sort of quick buck fix Japan though? Did Japan need fixing in the first place?

You’re reasoning from a price change.

What do you think did rates of credit default swaps say of institutions who had those “High-Grade Structured Credit Enhanced Leveraged Funds” filled with subprime loans a few years before TSHTF in the housing market ?

Are you really sure the facts you are citing prove what you think they prove?

Please note that I am not saying the US can’t go Japan, I am just saying that your facts don’t prove much if anything at all.

Personally, I simply don’t believe anything Yellen said yesterday- the Funds Rate won’t be raised anytime in the next 10 years, in my opinion. What you are seeing is an attempt to make everything look “normal”. That “six months” will stay six months for a long, long, long time.

Hahahaaha……..so raising the interest rates leads to inflation now? You got it backwards. Higher interest rates mean tighter credit.

what happens if the yield curve keeps shifting up? Demand for credit falls and the economy slows. You have disinflation, not inflation.

Seriously, c’mon.

Commercial banks have trillions of dollars in excess reserves on deposit at the Fed earning a paltry .25%. Higher interest rates will make it more attractive to lend against those reserves. Right now that safe quarter percent looks good relative to the risks associated with lending at 2%, or whatever the current rate is, but at some point (5%?, 7%?), the banks may be willing lower their underwriting standards to take the risk. This has the potential to increase the money supply tremendously.

Yes, at some point higher rates would likely reduce demand for credit, but nobody knows what that point is. In the early 1980s people were getting mortgages at 16% and, although not happy to pay it, glad they were able to borrow.