See the Knots the Federal Government Is In, Regarding “Social Cost of Carbon”

This is pretty funny. In my Senate testimony one of the key points I made was that the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidelines state that federal agencies are supposed to do cost/benefit calculations using both a 3% and a 7% discount rate. Yet the Obama Administration Working Group only used 3% and 5% when estimating the “social cost of carbon.” My conjecture was that they avoided the 7% figure since it would show a SCC close to $0/ton, if not negative, making it awkward to clamor for immediate action to stop the catastrophe brewing before our very eyes.

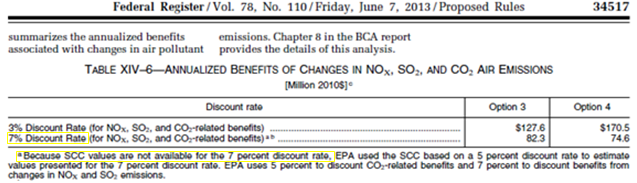

To see just how serious a pickle they are in, consider EPA’s discussion of a proposed regulation on steam electric power plants. Look at this shot of a table summarizing their results:

See the part in yellow? The EPA is dutifully following Executive Branch guidelines, as laid out by the OMB. They are reporting the estimated benefits of the proposed rule at both a 3% and 7% rate. Yet, since one component of the benefits is the reduction in CO2, they have to include a footnote explaining that actually, they will be plugging in the number for a 5% discount rate, since the social cost of carbon (SCC) at a 7% rate is “not available.” (Note that the modeled benefits from reducing NOx and SO2 aren’t about climate change, but are considered direct health hazards. That’s why computing their harms–and the corresponding benefits from reductions–doesn’t do anything screwy going from 5% to 7% discount rates, as does the “social cost of carbon” since climate change is actually beneficial, according to the government’s own suite of models, for the next few decades.)

I hope this underscores just how screwy this is. From now on, federal agencies will have to include footnotes in all of their cost/benefit tables, since the Working Group explicitly chose not to estimate the number that they are all required to plug into their calculations.

To be crystal clear: The Working Group ignored the OMB guidelines, but at least reported accurately on their number: They said it was a 5% rate when giving those figures. Yet the EPA rule above, and others like it from now on, will be reporting the benefits of various rules at the “7%” rate while including the social benefits of CO2 emission reductions at the 5% rate. In other words, they are literally plugging in the wrong number; they have no choice.

Now here’s the important question: can you explain this any more clearly, as in clearly enough for your average journalist to faithfully report this info in a mainstream news article?

Because they really seem to struggle with simple stuff like this.

The willingness to pay for mortality risk reductions, as is used by the federal government and academics to value criteria pollutant related benefits, is a consumption equivalent measure. Therefore those benefits should only be discounted using the 3% rate as per OMB guidance in Circular A-4. OMB specifically notes that 7% was not meant to represent a consumption discount rate. According to the documentation provided, the SCC estimates used by the federal government are also consumption equivalent measures. Therefore as per OMB guidance (and standard economic theory) should only be discounted using consumption discount rates also (of which 7% is clearly not). Therefore the only real inconsistency you are pointing out is that no federal agency should be using the 7% discount rate to value mortality risk reductions or they are running afoul of OMB guidance.

The degree to which the costs associated with mitigation policies will offset investment is a different question. I would suggest familiarizing yourself with this very important distinction before ranting.

John wrote:

I would suggest familiarizing yourself with this very important distinction before ranting.

I am continually astounded by the people in this debate. The table clearly says it is showing the benefits of the proposed rule at a 7% rate, and then in a footnote says it actually plugs in the 5% numbers because the 7% rate is not available. I mention this fact, and you accuse me of ignorance.

My dissertation was on time preference, thanks. I have a book on my shelf devoted exclusively to the topic of using discount rates in public policy analysis. I get the distinction, John.

Can you please explain it to me? Because I don’t get why consumption would discount slower than anything else… who gets to decide what is consumption, and on what basis?

Bob’s response above is, of course, 110% dead on. But I do have to admit I get a certain amount of pleasure from seeing him get the Bob Roddis treatment – not because I wish that on anyone but because it’s interesting to see his response. I thought he handled it like a champ.

What do you mean? John didn’t accuse me of basic ignorance of economic calculation.

And given the amount of ignorance of what the Austrians mean by economic calculation in their critique, Roddis isn’t in the realm of absurdity.

I mean, the Keynesians aren’t like the Georgists, declaring that the economic calculation critique only applies to centrally planned economies. Oh, wait…. yeah, a lot of them actually do assert that on occasion…

If he’s not in the realm of absurdity he’s definitely got a PO Box there…

And LK? Roddis may be quick to assert that someone doesn’t understand Mises and Rothbard on economic calculation, but he’s often right about that, too…

If he’s not in the realm of absurdity he’s definitely got a PO Box there…

Nice trolling.

Or worse, they assert that economic calculation, rather than being the process of calculating the most effective use of means to attain presently and future desired ends in the market, is simply the “notion of price flexibility allegedly leading to market clearing equilibrium prices that clear all markets, including the labour market” (“Lord Keynes”)…

My comment was in response to your statement “My conjecture was that they avoided the 7% figure since it would show a SCC close to $0/ton, if not negative”.

I had interpreted your post, including that comment, to be suggesting that to avoid this “skrewyness” that the governmet should estimate the SCC at 7%. Noting that in fact using a 7% discount rate for the SCC (and criteria pollutant health benefits) would be incorrect both theoretically and according to OMB guidance. The more correct solution would be to evaluate all of these benefits at 3% and dropping the “7%” estimates in the table. If that is in fact what you were suggesting then my apologies for misinterpreting your post, but suggesting that they “fix” the incorrect usage of a 7% rate for consumption equivalent criteria pollutant benefits by incorrectly discounting consumption equivalent carbon pollution benefits would be in itself skrewy.

John wrote:

Noting that in fact using a 7% discount rate for the SCC (and criteria pollutant health benefits) would be incorrect both theoretically and according to OMB guidance.

No, John, you are simply wrong. Even after the OMB explicitly discussed the work of Weitzman, it said an agency could use a lower discount rate if it wanted, in addition to the 3% and 7% figures. You can say they should NOT have written that, but it’s what in fact they wrote. That’s why this whole thing is so funny.

If you don’t believe me, look at page 4 at the bottom of my written testimony. I put the relevant part in bold. I really wish you guys would read what the OMB actually wrote, before accusing me of ignorance.

When I do finance models in excel I have a variable called interest rate (discount rate) and it is a fixed cell that can be entered anywhere in the model to discount cash flows. I only have to change one cell and the whole model picks up the new interest rate.

I know you know this, but for them to claim they cannot do a 7% is just bogus. That, or their model is making the most basic of mistakes…

It is too easy.

Well von Pepe, the Working Group has told some of us (over email) that they didn’t save the intermediate results from the thousands of computer simulations. The problem is that it’s not just a single point estimate of damages at each year in the future, but there are several different permutations and it’s drawing from a random distribution of climate sensitivity, so they want thousands of model runs to get a distribution of the SCC (not a point estimate).

I think they should’ve saved the averaged damage estimates by year, through 2299, so we could tweak the discount rate like you’re saying, but I’m explaining why they are claiming they can’t do it now.

Even in the extemely unlikely event that they can’t trivially regenerate values for arbitrary discount rates …

A) They could publish the future social cost curves from which the PV is calculated so that other Excel wizards could do the work.

B) they could publish costs per ton of carbon for a range of rates so that we can at least interpolate to arbitrary values.

Looks like just another case of people hiding behind fake expertise.

So kinda like a Monte Carlo?

I stil think anywhere it says divide by discount rate in the model it should be able to draw from one number entered.

So what is your recommendation in the end? Should OMB be revising its guidance to correct these issues? Or are you suggesting that consumption equivalent benefits should be discounted at 7%?

If it’s going to use 5%, it should say 5%. If it wants to use 7%, it should do that. Not try to shoehorn 5% into a 7% figure and basically say “close enough”.

I fully agree with that. But I am curious as to whether you think a constant 7% is an appropriate value for the social consumption discount rate?

That’s the question for the government, because THEY said that every cost- benefit analysis must include the 7% value. If you want to criticize the government for the choice of this particular number, please do that. Don;t criticize instead the people who try to hold them accountable for following their own guidelines.

I’m not criticizing anyone. I’m asking you, as a self proclaimed expert in discounting, what _you_ think the theoretically appropriate consumption discount rate is?

John,

There are lots of nuances in this debate. For sure, I think it’s wrong to take the after-tax yield on US Treasuries that had a maturity of at most 30 years–and which were highly liquid throughout that entire period–and treat that as a proxy for how much the average Earthling would discount a project that would pay another average Earthling $100 in the year 2113. The discount rate on the latter should be a lot higher than the former.

I’m still waiting on a satisfactory definition of Social Cost… that’s how far behind I am in all this.

What’s wrong with the standard definition?

Don’t get me started.

What problem do Austrians have with social welfare? Is it that it assumes interpersonal utility comparisons? I think you can construct it without relying on them.

The problem is that only individuals can be better or worse off, not “society”. When you ignore that people are individuals, and instead treat them as if they were supposed to be unified in their economic goals, you hinder economic calculation.

Most of the justification for welfare comes from the economic crashes that are caused by government interventions.

Once that is understood, the only question remaining should be: Is there any benefit to thinking of people in terms of a society as far as economic policy is concerned.

It is assumed by those who think so that because a free market would result in an unequal distribution of wealth (which is true) that it is necessarily exploitative.

But as Joseph Salerno explains in the following video, the businessman doesn’t control the economy – the consumer does; The businessman only gets rich when he satisfies consumer wants [or when government interventions protect him from competition – which is not a free market]:

The Birth of the Austrian School | Josep T. Salerno

[WWW]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZRZKX5zAD4

Some people are better at satisfying consumer preferences than others; Those people SHOULD be richer than the others – that makes perfect sense.

That’s a statement of belief, not backed by any real proof.

However, I challenge anyone calculating social costs to explicitly document how they went about asking society what its preferences are. There are a number of conceivable ways to do this (e.g. have an election for example) but all of them have some difficulties, and the majority of people who promote “externalities” and “social costs” will simply avoid the question.

The standard method is not to ask people their preferences, but to use revealed preference studies.

“That’s a statement of belief, not backed by any real proof.”

On the contrary, there is no actual entity “society” that can be measured, and no way to measure “being better off” across multiple individuals (although one can say that an action may not result in any of them being *worse* off). And individuals cannot have their preferences compared, so the only useful “welfare” scheme that could “make society better off” is that of voluntary charity and mutual aid societies.

That’s a statement of belief, not backed by any real proof.

“Better off” can only be assessed by individuals.

If, on your own terms, society can consist of individuals with conflicting preferences, then the word “society” loses its meaning.

The fact of scarcity ensures a conflict of preferences (not all preferences for a given scarce resources can be fulfilled).

Any allocation of resources that do not coincide with voluntary transactions benefit one party at the expense of another.

And so all regulations necessarily entail cronyism.

… use revealed preference studies.

I may as well mention this again, down here:

Policies restrict the revelation of preferences, so that when preferences change, Policy A will involve tyranny.

Joseph Salerno addressed the essence of the “use revealed preferences to determine policy” argument, here:

Calculation and Socialism | Joseph T. Salerno

[WWW]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KseRuyAjlHY#t=54m54s

“That’s a statement of belief, not backed by any real proof.”

Now now Tel, let’s not take the game of “If I haven’t seen it, then it does not exist” too far.

Social welfare analysis doesn’t assume that people have unified goals. The Pareto efficiency criterion treats people as individuals, not as some abstract thing called “society”.

Pareto is ignored when looking at social welfare. If he was not, then one would realize that they are performing interpersonal utility comparisons that are invalid.

Pareto improvements are not explanations of social welfare. They are explanations of individual welfare.

Both Pareto efficiency and social welfare are based on individual welfare.

Both Pareto efficiency and social welfare are based on individual welfare.

Individual welfare ignores the concept of “society”, and social welfare ignores the concept of the individual.

They are mutually exclusive concepts.

Society is a function of the individuals which comprise it, and so there is no reason to consider “society” when determining policy.

The individuals which created the arbitration service get to decide how they will contract with each other, and no one else.

Such an arbitration service either serves all individuals’ preferences, or some individuals stop contracting with the others. Either way, there is no coercion or central planning involved.

Not necessarily guest, if you constrain social welfare to MEAN individual welfare.

Libertarians for example hold that if all individuals are free to seek their goals, then that is a social welfare gain.

If we define society as all individuals, then individual welfare overlaps with social welfare 100%.

The problem arises when people start to define social welfare in terms of special interest groups, that is, in terms of only portions of the total population of individuals.

Definitions used, often unintended and subconcious, are “the state”, or “the majority”, etc. When “society” is defined in this way, THEN you can talk of “mutually exclusive”, because then you’d be talking about one group of individuals coercing another group of individuals, and here you would have an issue of “mutually exclusive” concepts antagonizing, or clashing with, one another.

So you are saying that every single person gets a veto here?

Can I use mine?

If we define society as all individuals, then individual welfare overlaps with social welfare 100%.

I see where you’re coming from.

Maybe I’m being overly cautious, but you see what the Left does with “all men are created equal”: They just reinterpreted the line to mean all men as a group.

They will probably take what you said to mean “See, social welfare CAN be synonymous with individual welfare”.

So you are saying that every single person gets a veto here?

The Law by Frederic Bastiat

[WWW]http://www.constitution.org/cmt/bastiat/the_law.html

If every person has the right to defend—even by force—his person, his liberty, and his property, then it follows that a group of men have the right to organize and support a common force to protect these rights constantly. Thus the principle of collective right—its reason for existing, its lawfulness—is based on individual right. And the common force that protects this collective right cannot logically have any other purpose or any other mission than that for which it acts as a substitute. Thus, since an individual cannot lawfully use force against the person, liberty, or property of another individual, then the common force—for the same reason—cannot lawfully be used to destroy the person, liberty, or property of individuals or groups.

“Is it that it assumes interpersonal utility comparisons? I think you can construct it without relying on them.”

Not being an Austrian I can’t say for sure but I think that’s one of their reasons, and if it’s true it’s a good one. Don’t you hit Arrow Impossibility if you cannot compare interpersonal utility? And that theorem is not really about voting but about the coherence and possiibility of a “collective preference”. In other words, what the Austrians say.

Arrow’s theorem has absolutely nothing to do with interpersonal utility comparisons. An interpersonal utility comparison is where you take the cardinal utility one person gets from something, and you compare it to the cardinal utility that someone else gets from something. Austrian’s don’t even believe in cardinal utility, only orderings of preferences, so they think that doesn’t make sense.

Arrow’s theorem is about a rule that takes orderings of preferences from different people, and tries to construct an ordering of preferences for the group. The theorem says that you can’t construct such a rule that’s “fair” as defined by certain conditions.

The only reason why “fairness” even arises in such a discussion is precisely because collective gains and collective costs do not exist, and when the idea of it is attempted to be put into action, where INDIVIDUALS live and breathe, it will necessarily infringe upon real world preferences and utility, and hence there arises a potential of “unfair” behavior.

If we only considered real world preferences, that is, individual preferences, and we allowed all individuals to seek their goals without coercion, and we disallowed all goal seeking that coerces other individuals, there would be no room for “fair” versus “unfair” distinction to arise. Every activity would be what it is, and the distinction between fair and unfair would cease to have any practical meaning.

“What’s wrong with the standard definition?”

It sounds vague as hell.

What’s vague about Steve Landsburg’s statement of the standard definition?

“Let A be a non-status-quo policy and let John be an individual with wealth W. John’s willingness-to-pay for policy A is that amount x such that John is indifferent between living in the status quo world on the one hand, and living in a world with policy A and whith his wealth reduced to W-x on the other hand. The social benefit of policy A is the sum of individual willingness-to-pay, where the sum is taken over all individuals for whom willingness-to-pay is positive. The social cost of policy A is the sum of individual willingness-to-pay, where the sum is taken over all individuals for whom willingness-to-pay is negative. The “social welfare gain” from adopting policy A is the social benefit minus the social cost. “

The “social welfare gain” from adopting policy A is the social benefit minus the social cost. “

Where did those whose willingness-to-pay is positive acquire the authority to exact x from those whose willingness-to-pay is negative?

Only individuals can benefit, not “society”.

Whether it’s morally justifiable to use the government to increase social welfare is another matter. But as I said, social welfare only talks about the benefits and costs for individuals, not some abstraction called society. That’s why it relies on Pareto efficiency.

“Social welfare” is a collective concept.

Are you saying that the act of adding individuals’ willingness to pay is illegitimate, or are you saying that sum shouldn’t be called “social cost”? Or are you saying it’s fine to calculate that sum, but it’s a useless concept? Well, important theorems of microeconomics have been proven about that sum.

Are you saying that the act of adding individuals’ willingness to pay is illegitimate …

Yes.

Adding implies that the individuals belong to a group, but only individuals can decide for themselves whether they agree with others.

If individuals agree to contract with each other, then there’s no reason to attempt to add their preferences.

Society is meant to refer to, that is, include, everyone, right Keshav?

Tell me how everyone can incur money costs, when money is exchanged among individuals, that is, for every dollar spent, there is someone who receives a dollar.

When you say “social costs are $50 billion” say, you are actually including $50 billion in gains…to the individuals who receive the $50 billion spent, and as such, you are not talking about everyone at all. You’d only be talking about those who spend money, and excluding those who receive money as if they are not a part of “society.”

How do you test “willingness to pay” where no market exists an no one actually pays anything? I just pick my favourite policy, set my willingness to pay at infinity, and that’s the winner, now you have to do what I say.

That’s why instead of relying what people say their preferences are, we rely on revealed preference.

But preferences change all the time, and policies restrict the revelation of preferences.

Only if “policies” are coercive.

Only if “policies” are coercive.

Agreed.

And by coercive, we mean coercive to any individual.

There is no other kind 🙂

“How do you test “willingness to pay” where no market exists an no one actually pays anything?”

You take the LACK of trading to be the evidence you need that individuals prefer others things more highly.

The lack of a market for underwater basket weaving classes does not mean we cannot say anything about the value of such a thing.

So Major Freedom, what do you object to in the notion of social cost? How does summing up the willingness to pay of each individual represent an interpersonal utility comparison?

… what do you object to in the notion of social cost?

This will be helpful:

Appendix B: “Collective Goods” and “External Benefits”: Two Arguments for Government Activity

[WWW]http://mises.org/media/6738/Appendix-B-Collective-Goods-and-External-Benefits-Two-Arguments-for-Government-Activity

I prefer a hamburger to a hotdog.

You prefer a hotdog to a hamburger.

Please tell me what it means to say that my preference for a hamburger over a hotdog “is added” to your preference for a hotdog over a hamburger.

Then, imagine how “we” will be better off with the “sum” of a hamburger “plus” a hotdog, as compared to…a hotdog (what I value less) “plus” a hamburger (what you value less).

The most likely reason you believe that this “sum” of costs concept has any economic meaning is because we typically incur MONEY costs when achieving our economic goals.

Thus:

I prefer a hamburger to $5.00. I trade my $5 for the seller’s hamburger.

You prefer a hotdog to $3.00. You trade your $3 for the seller’s hotdog.

Oh look! There are two numerical quantities here. $5 and $3. Oh, and they are both costs incurred in the course of goal seeking (eating a hamburger and eating a hotdog respectively).

ERGO (and this is the non-sequitur), there is a “social cost” of $8, and a “social gain” of, well, a hamburger “plus” a hotdog.

But it is wrong to say that “social gains is higher than social costs”. Why? Because the $5 is a gain to the seller of hamburgers, and the $3 is a gain to the seller of hotdogs, while the hamburger is a cost to the seller of the hamburger, and the hotdog is a cost to the seller of the hotdog.

What we thought were costs, are in fact gains as well, if we think from the perspective of those who subjectively value the things you give up differently than you in terms of where in their ranking scale they reside.

Or, think of it this way:

If you trade your $3 for someone else’s hotdog, and I trade my $5 for someone else’s hamburger, then there are actually 4 gains, and 4 costs. All 4 elements (hamburger, hotdog, $5, $3) are both gains and costs, from the perspective of each individual in our example (you, me, hamburger seller, hotdog seller).

The point is that it is actually meaningless to “add” subjective preferences.

They are not quantifiable because there is no fixed objective standard of measurement in subjective preference making. You can’t add different subjective scales of ranked values.

There are many other ways of explaining the same basic intuition. I’ve given only some. There are more that might make more sense to you.

So I have $10 and buy a box of bananas… what does this tell you about how much I value that red Ferrari in the showroom across the road?

What does this tell you about Global Warming? Not much I would guess, but certainly nothing directly related to the $10 transaction you can observe.

House Republicans support comprehensive tax reform to get Americans working again and our economy back on track. Independent economists estimate that, when coupled with reduced federal spending, comprehensive tax reform could lead to the creation of 1 million jobs in the first year alone. The Ways and Means Committee held 20 separate hearings on comprehensive tax reform in the 112th Congress, released an international tax reform discussion draft in October 2011 and released a financial products discussion draft in January 2013. In February, Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) and Ranking Member Sander Levin (D-MI) announced the formation of 11 separate Ways and Means Committee Tax Reform Working Groups. You can learn more about the working groups and tax reform below. What’s your idea for tax reform? Share your thoughts by visiting http://www.TaxReform.gov or tweeting @simplertaxes .

I have a question for the hardcore Austrians here (MF, guest, and others):

If you do not believe that comparing social benefits and costs is valid, then on what economic grounds can you argue for or against any particular policies? For instance, the standard economic case against trade barriers is that they reduce total surplus. The removal of a tariff benefits consumers and exporters, but it hurts domestic producers in the protected industry. Yet using a simple supply and demand framework we can easily show that the gain to consumers outweighs the loss to producers (the scales tip even further when we consider the political economy critiques of protectionism). Do you reject this argument? If so, then on what economic basis do you support free trade? You are of course free to argue that a laissez-faire policy accords with your moral beliefs, but by doing so you would be leaving the realm of economics.

And MF, in your hamburger and hotdog example above – we can, at least in theory, measure the gains to consumer and producer surplus in both exchanges by considering the consumers’ willingness to pay, the producers’ opportunity costs, and the exchange price. This is of course difficult in practice, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t theoretically valid or at least worth attempting to estimate.

MF and guest: you both reject the notion of society being made better or worse off, and say that only individuals can be made better or worse off. But all economists mean by society is the collection of individuals. Suppose a particular discovery makes every single person feel subjectively happier. Is it wrong to say that the discovery has made society better off? How about this: In a society of 1,000,000 people, someone invents a device that allows 999,999 of them to treat any disease and regrow any limb, but 1 person has to get his hair cut slightly shorter than he prefers one time. Would you really dispute that this invention makes society better off?

For the record – I don’t post here often so I want to state where I’m coming from – I think the Austrian School has a lot of excellent insights, and in fact it was stumbling upon mises.org that inspired me to study economics in the first place. But I do think the more hardcore Austrians err in their blanket repudiation of quantitative methods. Cost-benefit analysis, mathematics generally, and especially statistics/econometrics play vital roles. Not every question in economics can be answered by appeal to the pure logic of human action. The hardcore Austrians’ refusal to submit their theories to empirical analysis, and sit snug in their partial equilibrium ceteris paribus two-link-causal-chain of reasoning strikes me as a grave pretense of knowledge.

http://blogs.telegraph.co.uk/news/jamesdelingpole/100232437/official-wind-turbines-are-an-iniquitous-assault-on-property-rights/

Here’s an interesting example of property rights in practice and the so called “revealed preferences”.

So a farmer puts up some windmills, and presumably gets paid for that by an energy company. His neighbours don’t like the windmills so they feel their property value has been reduced. So does this farmer now owe a debt to his neighbours equal to their “willingness to pay” ?

First problem is that there may be some dispute over exactly what “property rights” entail in this situation. Do you own the view from your land? Let’s presume to avoid this problem, suppose that property rights stop exactly at the border of your land an anyone can build anything they want at any time.

Second problem is no one knows what this farmer is getting paid to run the windmills, and very likely they never got advance warning, so they can’t attempt to pay him not to do it because they don’t know what they are bidding against. Let us also ignore this problem and say the farmer did explain everything to his neighbours and they did in fact put in a bid, but the energy company ended up putting in a slightly higher bid. Let’s say the neighbours offered $1 million per year to not build, but the energy company offered $1.1 million per year if the farmer did build, so the farmer took the energy company’s money.

This would be an “externality” right? So the farmer must be made to pay $1 million per year to his neighbours as compensation (which was their offer) and he gets to keep $100k per year. Except that, if the farmer had NOT allowed the mills, he would have been entitled to $1 million per year in compensation the other way from his neighbours — a much better deal, so he would not have built. Except that in a rational environment the neighbours would factor this in and never offer more than $550k because why would they want to compensate more than necessary?

It gets even sillier when the energy company then approaches the next farmer down the road and makes another offer of $1.1 million, so now the neighbours are facing the prospect of paying a second $550k to keep their lovely view. Pretty soon a bunch of farmers get to it and eventually it looks like the neighbours are at the limit of what they can spend and ready to throw in the towel.

But now, if the third or fourth farmer finally does build the windmills, and then spoilt the view for everyone, there’s no point paying the first or second farmer any more… so these farmers have to start also paying other farmers to not build in order to keep their own revenue stream intact!

Recursion soup. Revealed preferences… load of cobblers.

“Do you own the view from your land?”

This is the only real relevant portion of your lengthy analysis because all of the other portions rest upon this question, and all of them are entirely wrong.

To put it simply: no, you do not own a “view” anymore than you own a word or an idea. These things are not scarce or rivalrous resources in a universal sense unless all actors in the economy demand that specific view, in which case the limitation has nothing to do with the view itself, but rather the amount of land afforded to those who wish to have such a specific view (which has nothing to do with the view itself, but is rather a limitation due to the scarcity of the land property that has such a view). Thus the view itself is not scarce and rivalrous, it is instead the land that offers such a view that is both scarce and rivalrous (you can only fit so many people in a given space).

The view itself does not meet the prerequisites of property of which a person can own. The limitation is rather the scarce property that has such a view.