Heads Krugman Wins, Tails Austerians Lose

Man I am just really down lately, because the great experiment in European austerity has proven to be a disaster for “my side” of the debate. You had all these austerians predicting that the way to reassure bond markets and get yields down on fiscally suspect European nations was to make bold promises about reform. But it’s not like this “unprecedented experiment in austerity” produced something that could be described as “The Italian Miracle,” right? It’s not like Krugman would write a blog post like this:

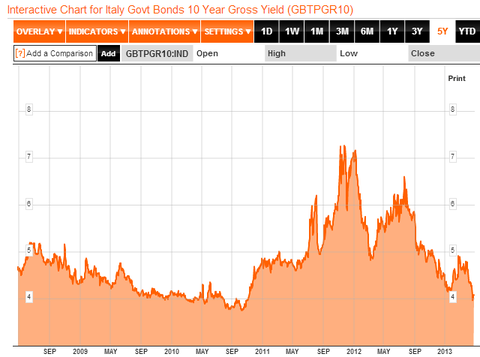

Italy is a mess. Yes, it has a prime minster, finally; but the chances of serious economic reform are minimal, the willingness to persist in ever-harsher austerity — which the Rehns of this world tell us is essential — is evaporating. It’s all bad. But a funny thing is happening:

What’s going on here? I think that we’re seeing strong evidence for the De Grauwe view that soaring rates in the European periphery had relatively little to do with solvency concerns, and were instead a case of market panic made possible by the fact that countries that joined the euro no longer had a lender of last resort, and were subject to potential liquidity crises.

What’s happened now is that the ECB sounds increasingly willing to act as the necessary lender, and that in general the softening of austerity rhetoric makes it seem less likely that Italy will be forced into default by sheer shortage of cash. Hence, falling yields and much-reduced pressure.

So here’s how you deal with data if you’re Paul Krugman:

(A) Describe what Europe is doing as the dream plan of right-wingers, even though I can’t think of any Austrian or Chicago School guy saying that raising tax rates was a good idea for Europe.

(B) Find any example of bad economic news in Europe, and blame it on “unprecedented austerity.”

(C) Find any example of good economic news in Europe–even falling bond yields, which is exactly what the politicians claimed would happen if they implemented their “austerity”–and attribute it to the ECB doing just enough to offset the horrible fiscal policy.

(D) Then, just for kicks, claim that only a liar or a fool could possibly ignore the mountains of empirical evidence that the Keynesians have been totally vindicated by events in Europe.

They engage data with minds nearly like a tabula rasa. It’s only the cold and hard facts that count for them. I mean come on they’d change their mind if the facts change, that is their motto…

😉

Another point is that these discipline mechanisms exist for a reason. An analogy is the banking system. Deposit insurance eliminated an important discipline mechanism, the bank run (well, on conventional banks). A lot of people see this as a great success, but it also means that bad banking outcomes go longer unnoticed. The same is true for fiscal matters. There are legitimate reasons that investors are worried. Krugman is essentially saying that the worrying is the problem, not all the issues that are worrying people in the first place. I don’t see how papering over these concerns by creating safety nets means that the problems investors are pinpointing are no longer relevant. Related, Krugman argues that first we should deal with the demand problem, and then with the structural problems. But, these structural problems are related to the demand problem, so by tackling them we can help stimulate a market-led recovery. I don’t get how Krugman gets away ignoring all of this.

Jonathan,

1) If the problem as Keynesians see it is a fall in aggregate demand due to investor psychology (“animal spirits”) why would would the steps Dr. Krugman advocates be a “papering over” of the problem?

2) By “structural problem” do you mean paying off debt? Again, if Keynesians see the problem as an aggregate demand problem, why would structural problems come first? I thought, per the Keynesian view, that problem can only be solved by addressing the demand problem (either by gov’t stimulus or chance).

In sum, what room is there for Keynesians not to ignore the problems as you state them? It seems to me they would have to see these problems as “structural” in the first place. That does not sound “Keynesian” to me.

Well, the question comes down to why the market can’t fix the demand problem on its own. Part of it is structural: inflexible labor markets, a moribund banking system, et cetera. There are reasons why the economy is depressed, and these are some of the same reasons private investment is as low as it is. If by solving some of these structural issues we can increase aggregate demand, it doesn’t make sense to ignore these solutions. And Krugman knows (or should know) these problems exist, because they’re precisely the reason that the disciplining process is distorted (through guarantees).

Part of it is structural: inflexible labor markets, a moribund banking system, et cetera

Okay, but, aren’t labor markets (for example) in the Keynesian* view inherently inflexible? That leaving this to the ‘market’ (IOW by letting these structural issues solve themselves – i.e. by letting wages adjust) is only leaving the solution of this ‘structural’ problem to chance?

I guess I just don’t see why a ‘disciplining’ problem should be of primary concern to economists like Krugman. I would think their position might be fine, discipline whomever (i.e. temporary nationalization), but get aggregate demand going again – you can’t solve the problem (or best solve it) by addressing structural problems (i.e. by letting wages adjust downwards).

* Broadly speaking – disregarding the distinction between Old and New Keynesian, etc.

But, surely, if they admit that they’re problems during the boom (which they do), they must also think they’re problems during the bust. Surely, if these structural issues were solved the demand shortage would be attenuated. This doesn’t mean Krugman can’t advocate fiscal stimulus. It just means that he should be more willing to admit that there are structural issues which if tackled would also help the recovery.

My original point, in any case, is that if investors are really concerned about something, and they’re disciplining their is debtors — something economists of all kinds usually consider, in a sense, positive –, then these problems are also relevant during the glut.

Jonathan,

First I want to clarify that I agree with you, and agreed with your original point. I think economists should be converned about the structural probelms – I think that is where the problem lies.

But, based on my understanding of the Keynesian position, I don’t see why an economist like Krugman would, or at least wouldn’t see structural problems as a priority. Take care of aggregate demand first -the structural problems will then work themselves out.

Fantastic!

(A) is where Krugman shows complete hypocrisy. He claims the US growth would have been better had we spent 1.5T. He claims that the continued weakness in the US PROVES his theory. What is ignored is the fact that Krugman got 50% of what he asked for and there were infinite other courses of action in response to the crisis of ’08. Making note of this is key, because Krugman would have you believe that Austrians endorse European “austerity”. Far from it. Us Austrians got 1% of what we wanted. Krugman got 50% of what he wanted. 99 wrong inputs and 1 correct input still = disaster!!!

(B) Bravo! Again the Krugmanites and Normanites can call practically any country’s fiscal policy “austere”, so long as growth in government slows, a program is cut, etc etc etc etc. This is like calling a Fiat 500 an Italian supercar. You can’t blame the net effect on a single input when there are countless other NON-AUSTERE factors. Correlation does not imply causation. Sure gov’t spending has slowed in those countries. This is along the lines of an Austrian policy, but nowhere near what an Austrian would promote. The recession/depression is necessary, yet the aforementioned act as if we said that our policies, once enacted, would be painless. We cannot simply have a 20′-21′ type of depression anymore.(short and painful)

(D) How do they get away with proving everything empirically? Correlation does not imply causation, yet they would have you believe that it does……. but only the correlation they want you to look at. I can empirically prove that rising obesity rates in the US cause higher standards of living. As obesity rates increase, so does I-Phone ownership. The point is that you can literally “prove” anything you want by picking and excluding any evidence at will.

I’m glad you got back to talking about “austerity” again, because I can sound important by quoting someone else discussing the exact same subject. By they way, Nikos makes a lot more sense than Krugman:

http://www.greekdefaultwatch.com/2013/04/is-austerity-debate-relevant-for-greece.html

Murphy, to believe your assertion, wouldn’t we have to keep ourselves blissfully unaware of current events? I mean, don’t you recognize that the sequence of events matters, and that is how one establishes CAUSE-AND-EFFECT?

If Italian bonds had never spiked upward, and there was never any media discussion about whether Italy would default or exit, and then had never come back down after Draghi put it in no uncertain terms that he would buy Italian bonds above 6% all day and all night long, sure, you could THEN accuse Krugman, validly, of having a shifty way of seeing things (Well, that is, if Italian unemployement weren’t so high, too….!?!?)

But as it is, look at the chart. What that chart says is that Italy was asking people to buy some bonds from Nov’11-Feb’12 and no one would buy until Italy ponied up >7%. Now why would people hold out? These people are buying Italian bonds at 7% – but that means there were some people waiting for 7.5%+. Those people are not betting Italy is going to default – they are generally betting ON Italy paying up. And if 7% makes you money – IF YOU BID and WON the bond, then why not 6%? Especially since 2 months later the rate was just 5%! Some people lost billions by not buying. Why would they do that? Not very rational.

Meanwhile, Italian unemployment is high and tight. Yup, you’re right, that austerity is going just great. Silly Krugman.

By the way: Mario Draghi took over the ECB when….? 1 Nov 2011. What a freakin’ coincidence, man! When did Draghi announce the LTRO program? 12 Feb 2012. Again, what an amazing coincidence. It is like the data is conspiring to make Krugman believe he’s right, but we all know he’s really wrong – sooner or later the data is going to pull the rug out from under him! hehehe. Can’t wait. That little badger. Bugs me.

Let me help you a little here.

Imagine that your worst enemy is an axe-murderer living in rural Vermont. You, being Paul Krugman, call him an “Austerian.” When it hits the newspapers that the “austerian” has, in fact, murdered people, you, being Paul Krugman, claim vindication for your view that Austrian economics is literally murder.

Still with me? Good.

Now imagine that you, J. Hansen, read a Murphy post refuting this Krugman posture. And you, J. Hansen, decide that Murphy must be an idiot for not knowing about the axe murders that clearly took place in rural Vermont.

Okay, we all have bad days where we don’t get the point.

This is one of yours.

Bob,

Don’t feel too down about the “failings of austerity” in Europe. I actually think it works out in favor of the Austrians’ side. It’s pretty much evidence that their economies were so bubbled up and structurally distorted from Keynesian-type policies for so long that the restructuring of their economies would take practically forever. After all, perpetual misallocation of resources in an economy over entire decades is sure to distort,at the physical level, the structure of capital. Furthermore, the Fed’s money printing binge actually exacerbates Europe’s problems because why would anyone build a factory in Europe when they can ride the US stock market to high heaven. Therefore, it would take forever to get the sort of capital that Europe needs to have a sustainable economic structure.

The same kind of applies to the US too, if we actually had a responsible Fed policy. For at least a decade we’ve been warping the capital structure, which surely shed sturdy components of the structure in order to accommodate the unsustainable structure.