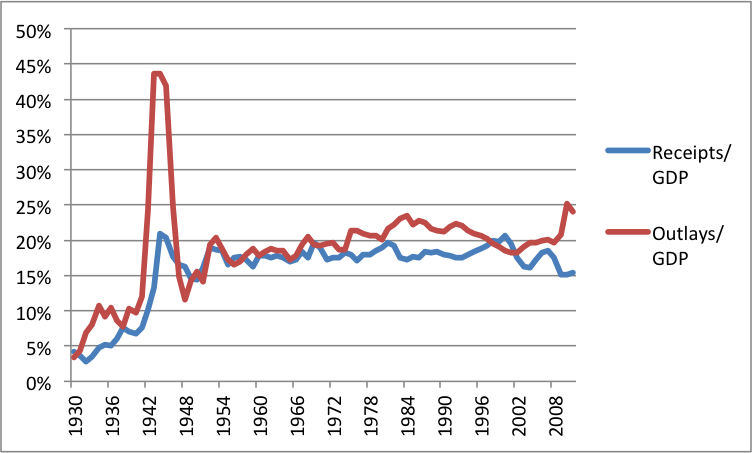

Federal Government Outlays and Receipts as % of Nominal GDP

Here you go kids:

So as I exclaimed in an earlier post, the receipts line shocked me. I have been working a lot with federal spending and knew about the WW2 bulge, but you can see how it crashed right after the war. (This gave rise to all the songs we still sing to this day, about the horrible 1946 depression…[crickets].)

I had just assumed that federal receipts followed a similar trend, but as you can see, they basically jacked up taxation big time for the war…and left it there.

Two things:

(1) Yes yes, I know there are problems with calculating nominal GDP etc. If you want to say that we shouldn’t be counting $1,000 in federal spending on tanks the same as $1,000 in private spending on cars, then the lines above would be even more pronounced during WW2.

(2) No no, I have no idea why WordPress stretches out my graphics. I have tried adjusted the “height” variable in the automatic code it generates when I upload an image, to no avail. The Internet works in mysterious ways, and I do not question it.

Also, you can see why Krugman is so totally right that it’s a right-wing myth about Obama being a big government spender… [more crickets.]

And the same phenomenon is at work for the 2008-2009 as in 1929-1933: the surge in spending as a % of GDP is partly a function of the GDP collapse. Thus your graph is misleading.

It’s not misleading if you aren’t mislead into believing what you think the graph maker is trying to say, as opposed to what they are actually trying to say.

Yes, the increase in spending is partly a function of the fall in GDP. But why didn’t stingy austerity driven Hoover decrease government spending as GDP fell? Why did he continue to spend and thus spend more relative to GDP?

Hoover wasn’t the stingy austerian that Keynesian cultists are claiming him to be.

It is larger than anyother time other than the war Bob, Krugman is a political hack now who rights for the left, he stopped being objective decades ago.

While you’re at it, check out that tight-fisted Herbert Hoover, Austerian Extraordinaire from Fiscal Years 1930-1933. [At this point the crickets are tired.]

Jeez, one major reason why your graph shows a surge under Hoover is that GDP collapsed by about 26.8%:

http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2011/12/us-real-gdp-and-gnp-19291950.html

It is not because Hoover was a some kind of hyper-profligate spender.

Hoover ran a federal budget surplus in fiscal 1930.

And Hoover’s increases in federal spending were not far from the 1920s trend rate until fiscal year 1932:

Fiscal 1927 – $2.857 billion

Fiscal 1928 – $2.961 billion (3.64% increase on 1927)

Fiscal 1929 – $3.127 billion (5.60% increase on 1928)

Fiscal 1930 – $3.320 billion (6.17% increase on 1929)

Fiscal 1931 – $3.577 billion (7.74% rise on 1930)

Fiscal 1932 – $4.659 billion (30.25% rise on 1931)

Fiscal 1933 – $4.598 billion (1.31% fall on 1932)

In fiscal 1933, total spending was cut.

Jeez, one major reason why your graph shows a surge under Hoover is that GDP collapsed by about 26.8%

So why didn’t the ultra-hawk stingy Hoover reduce government spending so that the spending to GDP ratio didn’t skyrocket?

Hoover ran a federal budget surplus in fiscal 1930.

He ran deficits 1931-1933.

And Hoover’s increases in federal spending were not far from the 1920s trend rate until fiscal year 1932:

Fiscal 1927 – $2.857 billion

Fiscal 1928 – $2.961 billion (3.64% increase on 1927)

Fiscal 1929 – $3.127 billion (5.60% increase on 1928)

Fiscal 1930 – $3.320 billion (6.17% increase on 1929)

Fiscal 1931 – $3.577 billion (7.74% rise on 1930)

Fiscal 1932 – $4.659 billion (30.25% rise on 1931)

Fiscal 1933 – $4.598 billion (1.31% fall on 1932)

I see a distinct increase in the rate of growth in government spending in 1930 and 1931, relative to 1927. 5.6% and 6.17% compared to 3.64%.

In fiscal 1933, total spending was cut.

By a mere $60 million, the spending of which was still far higher than 1928.

Murphy, your sense of humor is unmatched on the econ blogosphere.

I almost spit out my tea when I read “At this point the crickets are tired.”

Here’s something you might enjoy:

Progressives tend to blame large deficits on collapsing receipts, and thus propose an increase in taxes. But your chart is ALSO entirely consistent with the theory that government expenditures go up when they can collect more taxes.

Notice how post war taxes fell, but they didn’t fall back to pre-war levels. The momentum of the increase in government during the war became “the new normal”. After all, without keeping the increased state, another Hitler-like tyrant might arise in Europe and take over the planet.

Good thing we were saved from living in a world controlled and policed by one dominant country. [The crickets have gotten their rest, and are now chirping once again].

Parkinsons’s second law?

“Progressives tend to blame large deficits on collapsing receipts, and thus propose an increase in taxes. But your chart is ALSO entirely consistent with the theory that government expenditures go up when they can collect more taxes. ”

Exactly. More people need to stop viewing taxes as a way to fix deficits, and rather view taxes as a subsidy for even more government spending.

Of course, spending will increase regardless of how much is taken in in taxes. We don’t need to add a reason to increase spending even more.

Try leaving the height and width variables blank, then the image should auto size to its normal size.

Bob Ross is awesome!

“I have been working a lot with federal spending and knew about the WW2 bulge, but you can see how it crashed right after the war. (This gave rise to all the songs we still sing to this day, about the horrible 1946 depression”

In fact, there was a technical depression (contraction in real output by 10% or more) from 1945-1947, as the US command economy was dismantled and converted from a wartime economy back into a peacetime economy:

Year | GDP* | Growth Rate

1943 | $1,883,100 | 16.37%

1944 | $2,035,200 | 8.07%

1945 | $2,012,400 | -1.12%

1946 | $1,792,200 | -10.9%

1947 | $1,776,100 | -0.89%

1948 | $1,854,200 | 4.39%

1949 | $1,844,700 | -0.51%

1950 | $2,006,000 | 8.74%

* Millions of 2005 dollars

http://www.measuringworth.com/datasets/usgdp/result.php

From its wartime peak in 1944 to 1947, GDP contracted by 12.7%. For GNP, the figure is 12.51%. That was indeed a technical depression, but a depression sui generis, of course.

http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/2011/12/us-real-gdp-and-gnp-19291950.html

Which is probably the greatest thing that ever happened. Rather than building things to destroy other things, the economy produced stuff to improve the standard of living.

I guess, however, to number crunchers and those that believe economic growth is limited strictly to an increase in GDP, this was a “depression”.

But Richie, don’t you get it? Reported GDP FELL!!! Don’t you like weapons of war? They contribute to GDP!

GDP! GDP! GDP!

I mean

USA! USA! USA!

Economy A: GDP 1000, Government spending 500, Private spending 500 or 1/2 GDP.

Economy B: GDP 800, Government spending 200, Private spending 600 or 3/4 GDP.

Obviously economy A is better for the private sector, because GDP is higher!

Even if individuals are free to have more of a say in what is produced, then we’re supposed to think they’re worse off regardless, because…the government is using up fewer resources!

Oh, and INB4 “This is just the widely accepted definition of recession. Typical Austrians. Defining words to suit their agenda.”

Then I laugh at Keynesians insisting on a definition that the government just so happened to be interested in for taxation purposes. Higher GDP means higher aggregate spending, and higher aggregate spending means more to tax.

It is just presented to impressionable people as the primary source for economic growth

Congrats on showing the futility of measuring standards of living using GDP.

GNP declined in 1946 despite unemployment being below 4%, which is way below the historical “normal” trend before or since 1946. This full employment was achieved with massive contractionary fiscal spending, and the government firing roughly 20% of its employees. And yet unemployment was below 4%.

There cannot be a better example of showing the consistency of Austrian theory with empirical data.

The typical Keynesian response to this is that there was “pent up demand” that rescued the economy from what would have plunged the economy into another Great Depression.

The statistics that you are citing is just one source along a long line of statistics that keeps changing. If you look at the statistical history of what happened in 1946, you’ll see it getting progressively worse over time!

In 1960, the Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957, the decline in GNP was 7.8%, and from 1944-1947, 9.8%.

In 1975, when the next edition was published, the decline was 12%, and the total downturn 1944-1947 was 14.2%.

By 1981, the Department of Commerce calculated a 14.7% drop, while 1944-1947 declined 17.4%.

In 1985, when the next edition was published, the decline was 19%.

What is causing this massive change? It’s primarily the continually changing calculation of inflation. Between 1960 and 1990, economists literally doubled their estimates of inflation for 1944-1947, thereby causing the real GNP decline to double.

There were substantial price controls in place 1944, but were abandoned by 1947, so official statistics based on controlled prices tend to overstate true prices in 1944, and overstate the true inflation at market-clearing prices observed between 1944-1947. Yet the statistical revisions have tended to increase the reported inflation 1944-1947. From this, the revisions reduced reported inflation during WW2.

Thus, in 1990, the Economic Report of the President reported the price deflator rose 13.8% from 1941-1945. In 1978 Economic Report however, the deflator changed to 20.3%. In 1975 Historical Statistics, it was 26.5%. In 1960 Historical Statistics, it was 29.7%.

Of course, it is possible that the earlier stats were flawed, and that the newer stats were more representative of reality. One way to get a sense of what happened is to ask what prices would have been, if historical trends held. Vedder et al (1991) did this, and they calculated prices rising by 46% from 1941 to 1945, as compared to official stats varying over time between 24% and 30%, and they calculated 13% from 1945-1948, as compared to official stats varying from 26% to 50%.

This stats are similar to what Friedman and Schwartz calculated. They calculated 44% price inflation 1941-1945, and 16% from 1945-1948.

Dividing money GNP by the estimated deflator, they get a decline of output of 6.5% in 1946, and an increase in output 1947. Since the increase in 1947 offset the decrease in 1946, they conclude that there was no decline at all 1945-1947, compared to the stats you cited which show a decline.

This is consistent with written commentary of the period, of the smooth transition to peacetime production, it is consistent with the notion that wartime inflation was vastly understated because of price controls, and thus as a consequence post wartime inflation was vastly overstated, thus generating too high of a post war deflator, and thus too low a post war real GNP.

Then there is the fact that GNP during wartime vastly overstated the actual wealth available to increase citizen’s standard of living, since a huge chuck of GNP consists of aircraft carriers, tanks, and other war related output.

Robert Higgs, who analyzed Kuznetz, Nordhaus and Tobin’s work, found that standards of living were NOT actually rising during the war, and consequently there was NO downturn in standards of living after the war.

In short, the statistics you’re citing you are claiming we should all take at face value, when there is far more to the story than what you are presenting by simply parroting the official statistics.

” Between 1960 and 1990, economists literally doubled their estimates of inflation for 1944-1947, thereby causing the real GNP decline to double.”

I see that the Ministry of Truth has been hard at work…..

Are these WH or CBO numbers?

White House (OMB).

Yeah, I figured that as soon as I saw the period in the late 90s.

Why are we all assuming that there’s a direct relationship between spending, taxation, and depression *only for that year*. If there were a 3 year delay on fiscal policy, the Keynesian story would be consistent.

“Truman’s budget surplus of 4.6% of GDP in fiscal year 1948 fell to 0.2% in fiscal year 1949, as spending went from $29.8 billion in 1948 to $38.8 billion in 1949, as automatic stabilizers kicked in. In fiscal year 1950 (July 1, 1949 to June 30 1950), the budget went into an actual deficit of 1.1% of GDP.”

(below) makes my eyes glaze over.

Yet another issue raised by your graph is fiscal history from the 1948 to 1950 period. The post war boom gave way to a recession from November 1948 to October 1949.

Truman’s budget surplus of 4.6% of GDP in fiscal year 1948 fell to 0.2% in fiscal year 1949, as spending went from $29.8 billion in 1948 to $38.8 billion in 1949, as automatic stabilizers kicked in. In fiscal year 1950 (July 1, 1949 to June 30 1950), the budget went into an actual deficit of 1.1% of GDP. Moreover, Congress had pushed through a tax cut in 1948, which boosted private spending in 1949. What we have here is classic Keynesian countercyclical fiscal policy. Some of the increases from 1950–1953 were, of course, related to the Korean war, but also to new social, welfare and military programs enacted under Truman. Government spending in both absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP surged from 1948 to 1953, fell slightly from 1953–1954 as the Korean war ended, but remained between about 15% and 20% of GDP throughout the classic era of Keynesian economics (1945–1973) – an unprecedented level to that point in American history. And the economy boomed.

Yet another issue raised by your graph is fiscal history from the 1948 to 1950 period. The post war boom gave way to a recession from November 1948 to October 1949.

Only if we accept that the statistics you’ve cited are accurate.

Truman’s budget surplus of 4.6% of GDP in fiscal year 1948 fell to 0.2% in fiscal year 1949, as spending went from $29.8 billion in 1948 to $38.8 billion in 1949, as automatic stabilizers kicked in. In fiscal year 1950 (July 1, 1949 to June 30 1950), the budget went into an actual deficit of 1.1% of GDP. Moreover, Congress had pushed through a tax cut in 1948, which boosted private spending in 1949. What we have here is classic Keynesian countercyclical fiscal policy. Some of the increases from 1950–1953 were, of course, related to the Korean war, but also to new social, welfare and military programs enacted under Truman. Government spending in both absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP surged from 1948 to 1953, fell slightly from 1953–1954 as the Korean war ended, but remained between about 15% and 20% of GDP throughout the classic era of Keynesian economics (1945–1973) – an unprecedented level to that point in American history. And the economy boomed.

The economy boomed less than it otherwise would have boomed, had government spending and taxation been lower than it was.

You’re conflating an absolute increase over time, with the notion that only government could have made it increase over time. If it did increase over time, it means the government didn’t spend and tax enough to make it stagnate, or fall over time.

It’s like a pickpocket taking someone’s earnings, in such a way that allows them to still increase their standard of living over time. The economist knows the pickpocket didn’t cause the increase in prosperity, but for some reason you believe the pickpocket is responsible for the man’s prosperity because you observe the man’s prosperity rising over time.

LK, you are a terrific number cruncher, but do you know anything about economics?

Awww, let the Keynesian cultist believe he is engaging in economic science.

Watching him mistake correlation for causation over and over and over again makes for excellent entertainment.

I mean how fun is it to watch a Keynesian cultist conclude that economic growth being lower with government spending than without it, is the same thing as government spending causing economic growth?

How fun is it to watch a Keynesian cultist conclude that because growth in prosperity occurred despite some pickpocketing taking place, that this represents “empirical evidence” that proves the theory that pickpocketing causes growth in the victim’s prosperity!

Isn’t that just hilarious? Economics would be boring without cultists like LK.

Where’s the graph of the average temperature in Alabama?

As David Ramsay Steele once pointed out, the 1946 “depression” is not just a problem for Keynesians. If the ABCT is correct, we should have had a downturn due to the massive “misallocation” of capital due to wartime production. Tank and artillery factories are not homogeneous goods that can magically be transformed into cars and refrigerators in the blink of an eye.

Lwaaks, I think this is totally wrong, but it is a fascinating argument. Can you point me to where DRS said it?

Here is the full context. His comment appeared on the Libertarian Alliance discussion group (Yahoo Groups):

DRS: I haven’t given much attention to these issues for the past 20 years, no doubt mainly because I am no longer in frequent contact with anyone who wants to argue for the Austrian position.

As to “rating the Austrians”, some Austrians had good things to say: Boehm-Bawerk’s criticism of Marx, and so forth. There are really two kinds of Austrians today: Misesians and people like Hayek who reject Misesian apriorism. I have a brief section on Misesian apriorism in FMTM explaining why it won’t work and Hayek, for instance, would agree completely with what I say there.

As to the trade cycle, I long ago rejected the Austrian theory in both its Misesian and Hayekian forms. In 1977-1980 I was greatly preoccupied with this, and talked a lot with people like Jeff Hummel, who had been reared, so to speak, on the Misesian theory (as a typical born-again Rothbardian of that day) and was questioning it.

I actually had more or less rejected the theory before I read “The Hayek Story”. Rantala read “The Hayek Story”, discussed it with LSE faculty, came to agree with it, and convinced me it was correct.

The distinctive thing about Austrian trade cycle theory is its view of “real” factors in the onset of the slump. Of course, much of what Mises and Hayek say overlaps with the “purely monetary” theories of people like Milton Friedman, and long before that, of people like Hawtrey. So there is no dispute that inflation of credit may create a phoney boom, followed by an uncomfortable period of adjustment. What is distinctive about the Austrian theory is that it says the specific physical form of the capital which is malinvested plays a crucial role in the onset of the slump. So, for example, if lengthening the production structure requires a particular type of big, expensive machine that has no use with a shorter production structure, then that machine will have to be written off as a loss, since it is not suitable to the “return to reality” when the boom is over.

What struck me very early about this (I think it crossed my mind when I read Rothbared’s book on the 1930s depression, around 1971) was that it’s an empirical claim, and at a quick glance, such physical incongruities don’t seem to loom all that large. So, if the production structure lengthens, you change the shape of investment into something more appropriate to a lower time-preference. Fair enough. But what does this really mean? Let’s say you have a factory. You start to use different types of machine tools, let’s say. Still, most of your factors will be just the same, or almost the same, as before: electricity, computers (or in the old days, office stationery), unskilled workers, workers with various types of skill such as accountants, engineers, salespeople, and managers, your factory building itself, your use of trucks to get materials into the factory and products out, and so on. In others words, the overwhelming majority of the factors you employ are not specific to higher or lower orders of production. It’s true that their application to specific tasks will shift a bit, but this goes on all the time, and is an inexact science at best.

Since the claim that physical incongruities are crucial is an empirical claim, I was then struck by the experience of the US at the end of World War II. If ever there was a case of an abrupt, almost overnight, mismatch between prior allocations of capital and today’s applications, we could hardly imagine a more spectacular example. Millions of people left the army and found civilian work. Hundreds of thousands of factories which had been producing military goods had to transform their operations into civilian production. Why was the whole system not seized by a violent slump?

To the purely monetary approach, this is simple and obvious. There was no violent contraction of the money supply, so there was no slump. But to the Austrians, what explanation could there possibly be? Their claim is that once the boom has got going it cannot be ended without a slump, and that this is so because of the need to suddenly re-allocate physical assets to completely new uses. But that re-allocation was obviously thousands of times greater in 1945 than it could ever be as the result of a few years of bank credit expansion, and yet there was no slump! The whole system adapted to the utterly changed conditions with amazing ease and smoothness.

This was what I thought before 1980, and I still think it today.

“The Hayek Story” was a revelation because it raised a different issue. Consumers are continually asserting their time preference by their buying every day. So there is no “lag”. Credit expansion cannot really change the allocation of capital in the higher order direction required by the Austrian theory, because consumers keep going into the stores and buying just as many groceries as they were before.

I actually had had a glimmering of something like this earlier. As I read Rothbard and Mises, I thought “How can the boom go on for so long? Why isn’t it all over within a few months?”

The Hayekian response to “The Hayek Story” is in terms of Hayek’s metaphor of the pile of honey. This has always struck me as quite feeble. The “purely monetary” theorists don’t dispute, they have always insisted, that inflation causes misallocation of capital. What they do deny is that this misallocation takes the form of an unsustainable lengthening of the production structure. And this bold vision of the Austrians is, I think, incorrect. Purely monetary disturbances are enough to account for the government’s role in creating slumps (though the government makes matters worse by other measures, for example trying to stop wages from falling at the end of a boom, which is precisely what ought to happen to get the slump over with quickly).

Actually, I now see a parallel between the Austrian trade cycle theory and other notions which used to be popular among libertarians. What a lot of these different notions share is the premiss that the spontaneous market order is a frail bloom that can easily be killed. So libertarians fifty years ago used to talk as if a welfare state or a lot of regulation would quickly take us to the Soviet system and thus the end of civilization.

The truth is that the market is amazingly resilient and capable of amazing adaptations, and this keeps growing all the time with higher real incomes and faster and more accurate communications. What this resilience means is that the market can take a lot of punishment and still function surprisingly well. And what that means is that a heavily regulated welfare capitalism is a lot less unstable than we used to suppose. Of course, deregulating would lead to greater efficiency and benefit everyone, and various crises will crop up now and then, like the crisis of the NHS in Britain and the crisis of “social security” (old age pensions) in the US, but a continual heavy burden of regulation and unfortunate sabotage by government is compatible, as a simple matter of fact, with indefinitely rising real incomes for everyone. Or if you want to translate this into Randian terms, Atlas never gets round to shrugging because Atlas is doing okay, and both Atlas and the looters can keep on improving their situation indefinitely. Atlas doesn’t notice the burden because his muscles are fully up to it, and they improve their tone with every passing year, despite the increasing absolute weight of the looters.

Cool stuff. What is the etiquette on this? Can I post it elsewhere and respond to it, or is that like ripping a page out of his personal journal?

Yahoo groups is a public forum for debate, so it is fair game. BTW, I solicited a response from an Austrian “big gun” who offered some good criticisms. I asked if I could post his email/response on the Libertarian Alliance forum but he did not respond (I doubt he would have cared). I decided to post it anonymously. What is the etiquette for sharing such things anonymously? I hope you do respond Bob, as Steele’s criticisms are very powerful, or at least seem so on the surface, and he is a very bright non-economist who once believed in ABCT. If you would like to see the “big gun” criticisms, let me know.

Please do respond. It is so obviously riddled with holes it would border on the criminal to not point at those holes.

“What is distinctive about the Austrian theory is that it says the specific physical form of the capital which is malinvested plays a crucial role in the onset of the slump.”

Where did this come from? I thought Austrian Theory was basically about intertemporal discoordination.

Austrians, as Steele points out (and see recent Freeman article by Peter Lewin), emphasize the heterogeneous nature of capital. As Lewin writes in another essay on the subprime crisis (paraphrasing): “An entrepreneur cannot turn a shipyard into automobiles.” Steele is challenging ABCT by pointing out that munitions factories after WW II were quickly transformed into consumer goods factories. Where’s the slump? WW II was a massive ‘misallocation’ of capital goods! It makes the housing boom pale in comparison.

My reply is on a new thread. I hate these “narrow conversations” 🙂

Hi Bob

css is resizing your image to a max width of 610px

line 610 http://consultingbyrpm.com/wp-content/themes/display/style.css

.blogentry img{

max-width:610px;

}

if you dont want it to scale then keep your image width 610 or less, or change the css

Iwaaks,

Looks like you didn’t read my reply. I said “I thought Austrian Theory was basically about intertemporal discoordination.” While I said that, I also assumed that anyone conversant with the Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle would complete the statement by adding (in their mind) “… through distortion of interest rates, which in turn is accomplished by massive credit expansion beyond the available pool of savings and corresponding monetary inflation.”

You need to explain why the boom of WW II is a typical boom caused by credit expansion and monetary inflation. Once you do that, we can get down to seeing whether what Steele said is a criticism of Austrian theory at all.

I think Steele sounds like one of the blind men in the parable of “The 5 Blind Men and the Elephant”. He seems to have caught on to the tail (difficulty in reallocating specific physical capital goods”) and decided that THAT is the ATBC. By forgetting about the rest of the ATBC, his “criticism” comes across as a strawman attack rather than a real one that merits any respect.

I did read your reply: I just didn’t provide a coherent response. I agree with your characterization of ABCT, but I think you have missed Steele’s point. Of course, the “malinvestments” of WW II were not induced by artificially low interest rates; but what Steele is saying is that the outcome — “misallocation of capital” — is very similar to what is supposed to happen when the Fed artificially lowers interest rates. You could say, in a sense, that the U.S. economy was ‘teleported’ after the close of WW II to where it would have been if a boom had been engineered by the Fed. If, as the Austrians claim, capital goods are heterogeneous — and there is massive misallocation of capital — why is there no slump? But even if Steele gets ABCT completely wrong, he can still ask, why, if capital is heterogeneous, why the U.S. economy so easily transitioned to a peacetime economy. It’s a good question regardless of Steele’s alleged mistakes, don’t you think?

“is very similar to what is supposed to happen when the Fed artificially lowers interest rates. You could say, in a sense, that the U.S. economy was ‘teleported’ after the close of WW II to where it would have been if a boom had been engineered by the Fed.”

Not exactly. A boom was generated in one particular industry – war preparedness – while every other industry was hobbled and shackled. Hardly your typical boom created by interest rate depression through credit expansion and monetary inflation.

“If, as the Austrians claim, capital goods are heterogeneous — and there is massive misallocation of capital — why is there no slump?”

A specific question for economic history to address and not for economic theory to explain. Above all, the absence of the slump is not an argument against the Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle.

“But even if Steele gets ABCT completely wrong”

Which, as I showed, he does, a point that is important considering that he is attacking ABCT.

“It’s a good question regardless of Steele’s alleged mistakes, don’t you think?”

A good question for economic chroniclers like LK, not for economic theory.

Iwaaks,

And where do I start on this gem?

” I thought “How can the boom go on for so long? Why isn’t it all over within a few months?” ”

I think he “thought” only for long enough to have this thought and blanked out the next micro-second.

Apparently Hicks had the same question and Steele didn’t like Hayek’s answer. What’s your response? I prefer analysis to ridicule.

How long the boom can go on depends on how free the market is to reveal the errors of the boom. On a free market, errors get revealed through failures of banks that engaged in monetary inflation to back their credit expansion. When a bank starts to run out of gold (the money) to meet the obligations on the fiduciary media i created and circulated, it will need to engage in credit contraction. When many banks do do, it triggers the bust. The bank run is the free-market’s bubble-pricking mechanism.

When, on the other hand, banks are protected from collapse by a central bank and people feel a certain (false) sense of safety through deposit insurance, bank runs can get deferred for very long periods of time allowing for longer booms and bigger busts. Note the increase in severity of the busts post-1913. Pray tell me how, if bank failures are actively prevented, the bubble can get pricked early.

I thought this was so fundamental and obvious that it was surprising to see a person who claims to be an expert missing it. If a novice like me can get it, what else can I offer an “expert” who does not get it anything but ridicule?

Steele does not claim to be an expert but I think he has a very good grasp of ABCT, which was why he so readily grasped the importance of Hicks’ criticism. The crux of the issue is how it is possible for a boom to go on for years if time preferences have not changed. This will impact the relative price structure immediately, not just in the long run. Other experts (also possibly deserving of ridicule) are Roger Garrison, Richard Ebeling and Hayek(!), all of whom think that Hicks’ criticism was worthy of response. Ebeling, in his review of Garrison’s _Time and Money_, addresses exactly the point Steele is raising. Here is an excerpt:

“And this brings us to Garrison’s explanation of the workings of the Austrian theory of the business cycle. The traditional Austrian story has run something like the following: the monetary authority increases the supply of credit and brings about a lowering of the market interest rate. This stimulates additional investment borrowing in longer-term capital projects. With the additional sums of money borrowed investors attract resources and labor away from short-term investment projects and consumer goods production. As these resource owners and workers spend the higher money incomes that have induced them into these new investment projects, they increase the money demand for consumer goods under the assumption that their underlying time preferences for consumption vs. savings have not changed.

The higher demand and rising prices in the consumer goods sectors of the economy enable consumer goods producers to bid back resources and workers into shorter-term investment and consumer goods manufacturing. Unless the monetary authority increases the money supply again, and once more lends the funds to sustain the longer-term investment projects that have been started, a downturn begins in the long-term investment sectors of the economy bringing the “boom” to an end.

Garrison finds this story unsatisfactory, due to a criticism made by Sir John Hicks in his essay, “The Hayek Story.” Hicks doubted the existence of any significant lag between when investors borrow the newly created money and when the borrowed money is paid out as higher factor incomes then spent on consumer goods. Thus it was unlikely that any long-term investment boom could get underway and be sustained for any prolonged period of time before consumer goods prices began to rise enough to chock off the boom in relatively short order. Yet, historically, investment booms have continued for years before the cycle has entered a downturn.

In the light of Hicks’ criticism, Garrison retells the Austrian story by taking his cue from the type of analysis used by the Monetarists in explaining how in the short-run a monetary expansion can push unemployment and resource use below the “natural rate of unemployment.” In the short-run, an economy always has some slack, even when it is operating at “full employment.” Workers can for a time be induced to work overtime and marginal workers who otherwise would not be drawn into employment under “normal” conditions can be added to the work force. Enterprises never operate their physical plant and equipment at one hundred percent of capacity, and also can be utilized above normal levels of operation for a period of time.

I knew all this before and it still does not make sense. It is not rising prices that pricks the boom (on the free market) but the forced credit contraction due to a surge in demands for redemption of notes and deposits in specie. Further, it takes some time for a loss of confidence in a bank to set it and for a rash of redemption requests to come in. When all banks expand together, various processes such as clearing houses reduce the pressure on specie redemption on individual banks. This further extends the “honeymoon” period for inflating banks.

Under Central Banking, all of the free market’s natural disciplining mechanisms are made inoperable and only political pressure over rising prices can lead to a rise in interest rates and a pricking of the bubble. The issue is, therefore, political. It is not an economic question but one of how long can the political class fool people about the truth behind the rising prices, i.e., inflation.

Why are you (and Steele) so keen about an economic explanation to an essentially political question? What if Economics cannot explain the length (meaning it cannot say how long the boom would be but recognises what it takes for it to be long) and you need to look elsewhere for the answer?

In simpler terms, the boom will go on until a credit contraction is forced upon the inflating banks. The question is “What will force a credit contraction on the inflating banking system?”

Take today’s situation for example. What will force a credit expansion today if a QE3 can be undertaken to kick the can down the road? The question is not whether QE3 is economic sense or nonsense. Rather, it is about whether or not they can pull off a QE3 and kick the can down the road. The way it looks, credit contraction will be forced upon the system when QEx will not enable a kicking of the can down the road. How long will that be? God alone knows!!!

Oops… I meant to ask “What will force a credit contraction…” and not “What will force a credit expansion….”.

Sorry.

You said this.

“Unless the monetary authority increases the money supply again, and once more lends the funds to sustain the longer-term investment projects that have been started, a downturn begins in the long-term investment sectors of the economy bringing the “boom” to an end.”

So, it all comes down to when the monetary authority decides not to increase the money supply again. That is not an economic question at all. There are different levels of survival they (Central Bankers) must be prepared to accept.