Debt Financing of Present Transfer Payments: May I Have Another, Sir?

[Note: I’m going to focus on Daniel Kuehn here, because this issue again sheds more light on all this stuff. I realize that we are all still not seeing what each person brings to the table in this debate.]

Ahh, now (I think) I finally get why Daniel Kuehn didn’t accept my wager: It’s not that he totally understood all this stuff from the get-go, it’s that in my wager, from the point of view of period 1, there will still “future generations” that benefited, and “future generations” that lost. So that’s why he was surprised I thought he would deny it. (I had been focusing on the fact that from period 6 onward, every “future generation” was strictly poorer.)

For those who have been following this (I guess you are probably about to get fired at your job, since you haven’t really been working the past week), here is a good sample of what Daniel was saying in response to my “The Economist Zone” saga:

I’ve got to confess I’m somewhat confused about the concern with the ordering of the burdened future generations (ie – cohesive sets of individuals who live across multiple periods with other similarly coherent sets of individuals who live across slightly different periods).

I didn’t think about this until your example either – whether after a certain period every generation carries a lifetime burden or not.

My question is – why does this matter? Who cares if the burden comes after a couple generations that benefit or before? Or perhaps the burden and benefit are alternating. What is the significance of this observation? What’s the value added on top of the fact that we know somebody in the future is going to be burdened?

So like I said, now I think I understand why Daniel can’t understand why I’ve been saying Krugman has totally misled his readers on this (I think unintentionally). Daniel, are you aware that this is possible with debt finance?

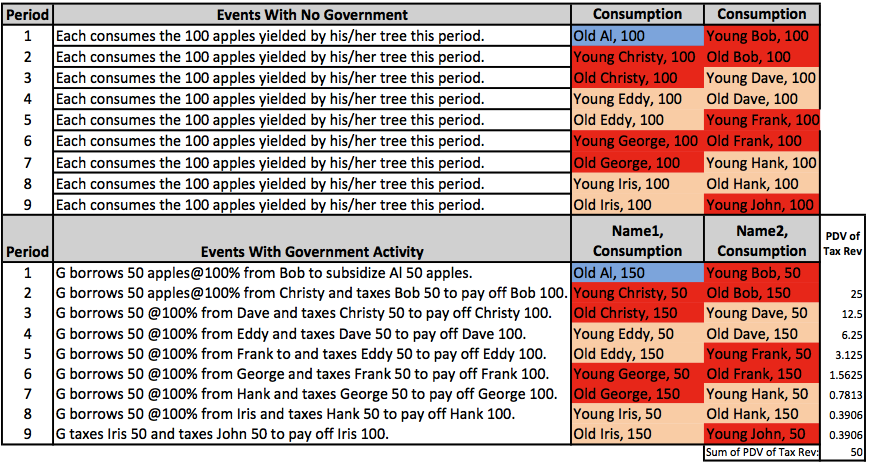

Everyone see how this one plays out? In period 1, Old Al clearly benefits. He gets a government transfer of 50 apples, paid for by a government budget deficit (there is no taxation in period 1).

Also note that I’ve put in the PDV of the tax receipts at each period. See how they sum up to 50 by the end? So one way to understand what is happening, is that the government gives Old Al a payment of 50 apples in period 1, and then spreads the tax burden to pay for it over everybody else (at some point in their lives) in periods 2 through 9. The government uses the bond market to pull all of that revenue forward in time, and give it as a spot payment to Al in period 1.

Now the crucial thing about this particular example I’ve constructed, is that Old Al is the only person who benefits from it, while every other single human being in the country, forever and ever and ever loses in this scenario. And yet, it is still the case that if we take any future time period, the “income earned by our descendants in period x is still 200 apples total.”

So when Krugman (effectively) tells us, “Don’t worry about imposing a burden on our descendants, because the total income they earn in each period will still be 200 apples,” that is extremely misleading.

And in light of the above diagram, I would like Daniel to reconcile it with his frequently stated position: “If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”.”

So I’m curious, Daniel, how do you reconcile the above outcome by saying, “If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose”? No, every single individual in the future loses. That’s why some of us have been jumping up and down screaming, warning people that Krugman is giving very bad guidance on this stuff.

NOTE: If it matters to some people, we could easily tweak the above example so that Old Bob and Young Al get more utility, while every other person from Christy through John gets less utility. Then it would true to say of such a world, “Every single person alive in period 1 benefits from the policies they–and only they–could vote on, while every single person who is born in period 2 or afterward loses, from an initial set of policies over which they had no control since they didn’t yet exist.” But, I didn’t use that one, because I was afraid Daniel would look at Bob benefiting in period 2 and say, “See, in this case Old Bob in period 2 is the guy who benefits ‘in the future.'” That’s why I’m going with my above example, where NOBODY in the future benefits, period.

Why do you have p.d.v? PDV is only important if there’s a market for future income streams. The Govt can create a product which is marketable to this end and in doing so shifts the ppf and gives a new Pareto optimium because there is a new Econ good on the table viz. claims to future apples. Indeed, if the Govt has a first mover or informational or other advantage then it secures a rent which permits your result (why would you want to prove this?) that deficit financing can be a Pareto improvement.

Is there any real world insight that prompted or that might redeem all this?

vik, yes, there’s a market for future apples here. People benefit by trading with the government.

(In this particular example they’re indifferent between buying bonds and not buying bonds, because I wanted to make the numbers easy.In this example, people would rather consume (50, 150) than (100, 50) which is what they’d get if they didn’t lend to the government, and just paid their tax bill when they were old.But in the Economist Zone story, everybody who lends money to the government gets more utility by doing so, assuming their future tax burdens are fixed.)But, don’t you see, your story is no longer a story about apples, but a story about incommensurable apples and oranges (oranges are apple futures). You can’t deduce anything from this.

It’s like Landsburg failing to see how an economic good, which in a first best world ought to be equimarginally taxed, is created the moment the State provides for Probate- in this case Estate taxes aint double taxes coz something new exists in the world viz. an economic good called a hedge upon one’s Estate (if death date is uncertain).

I urge you to cast your intuitions in the language of Game Theoretic ESS. You’ve really gone of the tracks here. You started by making a good point. Landsburg was and is egregiously wrong.. vide http://socioproctology.blogspot.com/2012/01/landsburg-getting-it-wrong-about-public.html-

but I don’t get why you’re making the point you’re now making.

It’s not consistent with the commendable point you started with and which is still correct.

Personally, I blame Landsburg. There’s something eerie about his reverse-Talmudic method of argument which manages to turn even quite sensible people topsy turvey.

When this discussion started I do admit I had not thought of a particular case where there isn’t anyone in the future who benefits. So this is a very interesting post.

I’ve never battled for the view that some individuals have to win over their lifetimes. I’ve only maintained that some individuals have to win in a given time period. But this clearly shows that distinction would have been good for me to make.

I’m sorry but I’m still missing what bad advice Krugman is giving here. Is the nation’s income lower in a future period in this case? If we consider a period in the future, is not true that some people gain and some people lose because debt creates both liabilities and assets?

Both of those points – those fundamental points that Krugman makes, the bedrock of his claim – are still true.

I don’t want to sound like I’m evading which is why I started how I did. You’ve expanded the scope of this debate more than anyone involved and in light of this post I do wish I had made previous statements differently. I’m still not sure why people want to pile on Krugman. That point still strikes me as being important, if for no other reason than it’s a point that taxpayers and voters routinely miss.

You say Krugman tells us this: “Don’t worry about imposing a burden on our descendants”. I still don’t see that. There are lots of tough decisions we have to make about debt.

“If we consider a period in the future, is not true that some people gain and some people lose because debt creates both liabilities and assets?”

“Both of those points – those fundamental points that Krugman makes, the bedrock of his claim – are still true.”

Just when you think the race already began, people are still at the starting line.

You’re right back at the very beginning of this thing, DK.

Suppose you have $100 in your left hand, and a piece of paper that says “Major_Freedom owes the bearer of this note $100 payable ASAP”. Assuming you hold my piece of paper to be a legitimate asset, what are your assets? $200 right?

Now suppose I take the money from your left hand, put it in your right hand, and then tear the piece of paper up.

Now what are your assets? $100.

You just lost $100 in assets.

NOBODY ELSE GAINED THAT $100 YOU LOST.

There is nobody there to “gain”, to “balance out” the loss you incurred, such that assets = liabilities, such that there is no collective loss.

“I’m still not sure why people want to pile on Krugman.”

The same reason you feel compelled to defend him.

“You say Krugman tells us this: “Don’t worry about imposing a burden on our descendants”. I still don’t see that.”

Krugman is responding to “descendants” as if it’s everyone collectively.

I “see” it:

“What you can see here is that there has been a big rise in debt, with a much smaller move into net debtor status for America as a whole; for the most part, the extra debt is money we owe to ourselves.”

“People think of debt’s role in the economy as if it were the same as what debt means for an individual: there’s a lot of money you have to pay to someone else. But that’s all wrong; the debt we create is basically money we owe to ourselves, and the burden it imposes does not involve a real transfer of resources.”

“That’s not to say that high debt can’t cause problems — it certainly can. But these are problems of distribution and incentives, not the burden of debt as is commonly understood. And as Dean says, talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children, which is a very different kettle of fish.”

Krugman is here saying that the “commonly understood” problem, of the layman’s understanding debt to cause “entire generations to be worse off”, he is saying that is false. That is saying “Don’t worry about imposing a debt on OUR DESCENDANTS.”

He didn’t mean “some people but not others.” He grouped descendants together.

This!!

“You say Krugman tells us this: ‘Don’t worry about imposing a burden on our descendants’. I still don’t see that.”

Daniel’s wording:

“Don’t worry about imposing a burden on our descendants.”

Krugman’s wording:

“Talking about leaving a burden to our children is nonsensical.”

The above statements are equivalent. Krugman was wrong. See it. Feel it. Be one with the universe.

Thanks for being cool about this Daniel, but I still feel like you’re pushing me to join David Brooks in the loony bin. You wrote this about Krugman:

“If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”.”

You now admit that that is simply false, right? And it’s not that you misinterpreted him, it’s that Krugman has been saying false things, right?

In other words, when Krugman told his readers (effectively) that our fiscal policies today couldn’t make future generations poorer, because “some people in the future will be richer if others are poorer,” he was saying things that are false, as my example in this post illustrates.

I’m not trying to get you to say, “You’re awesome Bob, Krugman should never have opened his mouth!” Rather, I’m trying to get you to see that this isn’t some nit I’m picking with Krugman, this is (in my opinion) the entire essence of how the layperson approaches this issue. The layperson feels guilty about living it up today, at the expense of our grandkids, and Krugman was quite clearly telling them that no, we couldn’t make our grandkids “collectively” poorer. But this example shows that yes we most certainly can.

Dude – the fact that you could write out that dialog between Brooks and me shows you can see what I’m saying without smoke coming out of his ears, the way the fictional Brooks did.

You and Nick just don’t think Krugman said what I think he said. That’s all. I don’t think we’ve disagreed on any fundamental conclusion of the models here.

re: “You now admit that that is simply false, right? And it’s not that you misinterpreted him, it’s that Krugman has been saying false things, right?”

Two points here:

A. What is simply false is that in the future there has to be some individual who wins from this over his lifetime. That didn’t occur to me one way or another until you explained it in this post. I accept now that it is simply false.

B. What is absolutely true is that within a given time period, some individual has to win if another loses.

Krugman didn’t have the ironing out of terminology and the excel tabs that we did so its hard to superimpose what he meant. He was talking about national income, and point B above falls out naturally from thinking about it in a “single time period” perspective. So it seems clear to me he’s saying the latter. You and Nick disagree and that little bit of exegesis. But that’s what it is – an exegesis food fight, not an economics food fight. That’s something at least.

“You and Nick just don’t think Krugman said what I think he said. That’s all.”

What did Krugman mean when he wrote this:

“That’s not to say that high debt can’t cause problems — it certainly can. But these are problems of distribution and incentives, not the burden of debt as is commonly understood. And as Dean says, talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children, which is a very different kettle of fish.”

Spell it out. What do you suppose he was referring to as the “commonly understood” problem of debt?

Spell it out. What do you suppose he was saying when he said (I can’t believe I am actually asking someone to tell me what someone else said when they said what they said. Oh well): “talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”?

What do you suppose he was referring as “especially nonsensical”?

What do you think he was trying to convey when he said “what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”?

“B. What is absolutely true is that within a given time period, some individual has to win if another loses.”

EVEN IF THERE ARE NO OTHER LOSERS IN THAT TIME PERIOD? Even if the person who lost, lost because his asset was simply eliminated such that he ends up with less, and nobody else gained what he lost?

Seriously? Are you even looking at the example? In the same period 9, Iris lost and John did not gain what Iris lost. That contradicts your claim that someone else MUST gain if someone loses.

“Krugman didn’t have the ironing out of terminology and the excel tabs that we did so its hard to superimpose what he meant.”

LOL, hilarious. So by “especially nonsensical”, he wasn’t referring to the “nonsensical” claim that “everyone” can lose, meaning some can lose with no equivalent gainers?

That he wasn’t saying the way Dean Baker put it is the correction to that nonsense, because “what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”, meaning if there are losers, there MUST be equivalent gainers who gain what was lost?

There’s denial DK, and then there’s what you are doing. You have redefined what is possible for denial. I think there should be a new word called “Kuehnial.” He’s not in denial, he’s in Kuehnial.

Correction:

“EVEN IF THERE ARE NO OTHER WINNERS IN THAT TIME PERIOD?

“In other words, when Krugman told his readers (effectively) that our fiscal policies today couldn’t make future generations poorer, because “some people in the future will be richer if others are poorer,” he was saying things that are false, as my example in this post illustrates.”

I’m sorry. The issue is not whether transfers involving debt *might* make future generations poorer. The issue is whether it is the debt that is key, or the transfer.

Or, in other words, does depicting a scenario in which government debt is used to impoverish future generations prove Krugman wrong? I say it does not, since (as Landsburg and I have demonstrated) we can always duplicate your debt scenarios with taxes and transfers. If that is so, then Krugman is correct: it is not government debt in and of itself that is the problem, but rather that seniors may suck resources from the juniors, which they can do via debt issuance, or via other routes. I.e., what I read Krugman as saying is that it is incorrect to view the mere existence of government debt as a burden on future generations. It is the direction of transfers that matters, whether they are funded with debt or taxation. And acknowledging that in no way denies that perhaps it might be easier to get away with such transfers via debt than via taxation, since citizens might resist a tax increase more strongly than a bond issue.

Gene Callahan wrote:

Or, in other words, does depicting a scenario in which government debt is used to impoverish future generations prove Krugman wrong? I say it does not, since (as Landsburg and I have demonstrated) we can always duplicate your debt scenarios with taxes and transfers. If that is so, then Krugman is correct: it is not government debt in and of itself that is the problem, but rather that seniors may suck resources from the juniors, which they can do via debt issuance, or via other routes.

No way, Gene. You show me one sentence fragment from everything Krugman has written on this, where he even hinted to his readers that the present generation could impoverish future generations through deficit finance, but that it wasn’t the debt “per se” doing the impoverishing. He absolutely did not spell out that second part of your and Landsburg’s claim.

Like I have maintained all along, I think the reason Landsburg (and now you) don’t see this, is that you guys never fell for the fallacy. But I did, and that’s exactly why I can tell it is what held (holds?) Dean Baker, Krugman, and Yglesias in its grip.

Look Gene, don’t you see the apparently unbeatable logic behind someone claiming: “Huh? How in the world can Old Bob and Young Al in period 1 do anything that would make people poorer in period 7? No matter what we do in period 1, the people in period 7 earn 200 apples in real income. The government at that time can only take apples from one person and give it to another. It is nonsense to say we can in any way impose a burden on them. All we can do is hand down pieces of paper instructing the government at that time–when we are all long dead–to take apples from one person to give to another. But it’s not like we can make both people in period 7 poorer? How the heck could we do that, without a time machine to suck away their apples so we can eat them now?”

Don’t you guys see the superficial appeal of that type of argument? That is what Krugman et al. were thinking, and not because they’re evil Keynesians, but because it seems right and would be right if there weren’t overlapping generations.

Maybe that will do it, Gene? Do you see how if you are thinking of my apple world without overlapping generations–where everybody just lives one period or everybody lives two periods but at any given time, both people are young or old–then we can’t get this result? In that world, Krugman et al. would be right.

And since nobody even thought this quirk mattered until Boudreaux and Rowe entered the debate, we would still all be thinking through the intuition in terms of “We’re all alive right now, in 50 years we’ll all be dead and our kids will be on the scene, in another 50 years they’ll be dead and our grandkids will be on the scene…”

Gene,

I think by playing with semantics, you are adding to the confusion, i.e. I do not think it matters at all for the current policy debate whether from a philisophical perspective it is debt or taxes or what have you, that are responsible for the transfer..Bob Murphys example makes ist cristal clear that the issuance of debt to finance consumption impoverishes (some) future generations in one way or another. Or economically more pricesely: the issuance of debt to finance NPV negative projects-as most gvt spending is either consumption or wasted investments. Yes, some of them by mere chance could be productive as well, although I am not sure…

it does not matter whether or not Krugman is right from a semantic perspective, i.e. by focusing on income. As an economist he should now that utility is what we are concerned the most with. So Bob is right to say, that this is highly misleading.

Furthermore I do not see how other than the issuance of debt or promises you could achieve an intergenerational transfer. Promises for future transfers that are voted for are a form of debt (think social security). clearly not all debt can be traded or shows up as such in gvt. accounting. But from an economic perspective promises are clearly debt.

The only way I see (correct me if wrong please) an intergenerational transfer without debt is if in each period the old outnumber the young and if the vote for taxes or policies that harm the young and benefit the old. this one involves no form of debt. Otherwise I do not know what you are talking about.

Best regards

Supposed you interpret Krugman 100% correct, then why doesn’t he write that in a clear and understandable way like you are doing here, especially if it is about the layman opinion in a column for the layman in the NYT? Not just imply all those things somehow that even PHD economists are fighting over its real meaning…

It would be nice to find out what most laymen are thinking before and after they read Krugman’s post. I’d bet everything but quite nothing of what you are saying above.

I think I know why Krugman would not make those clear statements you are making. It just wouldn’t look good to show people Bobs XLS and say what you said above and finally add: ”We need tons of government spending on preparation for an alien invasion financed with borrowing.” (I know that the alien invasion is an extreme example Keynesians not really favor).

My post is addressed to Gene. (Was a bit slow with publishing…)

I basically agree with what has been said in each of the posts today. I just have a few comments which I’m sure the length of which will defend it well against the risk of being read…

Apparently Krugman can only see accounting tautologies since that’s the only kind of truth which can be derived from the article. So yes, the taxes collected for the purpose of paying bondholders does equal the amount of money received by bondholders from the government paying down its debt to them in that same time period. Congratulations Krugman, you observed that no burden can be placed on a single time period after using simplifying assumptions which reduce actions to accounting tautologies and assure that no burden can be placed on a specific time period. Thus, the total real income in the period is the total real income in the period is the total real income in the period. What Krugman failed to observe, however, is the existence of overlapping generations in a single time period. By definition, these generations will be alive for more than one period, which whenever government finances its action with debt, leads to a burden which is to be carried until it is fully realized through taxation. The burden is due to the fact that whenever a government sells a bond, it is making a promise which it can only fulfill by harming someone else through taxation or by making another similar promise again. I’m not sure anyone has made exactly this point. It’s illustrated better with this example:

Population consists of two groups, young and old.

Period 1- A is old and B is young

Period 2- B is old and C is young

Period 3- C is old and D is young

i) A receives transfer paid for by bonds bought by B in period 1 which are paid off by taxes levied onto C in period 2.

Result: A and B are better off at the expense of younger generation C.

ii) A receives transfer paid for by bonds bought by B in period 1 which are paid off by taxes levied onto B in period 2.

Result: A is better off at the expense of younger generation B.

Analysis: B gives up consumption in period 1 for an asset in the form of a promise to be able to consume more in period 2 to be financed through the government revenue in period 2. Unfortunately for B, the government revenue in question was originally B’s period 2 revenue. Thus, though the bond was paid, the promise was not fulfilled and B sacrificed a portion of his period 1 consumption in return for nothing. The result is that the money used to purchase the bond in the first period was essentially turned into a tax.

Note: Although I’m not denying the theoretical possibility of a sustainable Ponzi scheme, I seriously doubt its empirical validity. Also, insomuch as Ricardian Equivalence is empirically valid, which I again seriously doubt, it does save future generations from the burden of government debt. However, the analysis is still flawed since it ignores the harm done to those who validate it.

Ricardian Equivalence

iii) A receives transfer paid for by bonds bought by A and bequeathed onto B in period 1. The bonds are paid off by a tax levied onto B in period 2.

Result: A, B, C, and D are indifferent.

iv) A receives transfer paid for by bonds bought by B in period 1. These bonds are bequeathed to C and finally paid off in period 3 by a tax levied onto D.

Result: A and C are better off at the expense of younger generations B and D.

Analysis: The claim that B is worse off is easily the most controversial one made in this entire discussion since he voluntary purchased the bond and voluntarily gave it up. However, in all the previous examples, B bought the bonds because he saw an opportunity to provide for additional consumption in period 2 which he valued more than the consumption he would have to give up in period 1, an action he would take under any circumstance. This situation, however, is quite different. B sees that a government transfer is going to be made to A which is also to be financed through government debt. Since B does not wish for future generations to pay for such a transfer, he is made worse off as soon as such a transfer is decided to take place. Therefore, that his actions were voluntary is irrelevant. They were two voluntary actions he would have originally preferred not to make.

iii) A receives transfer paid for by bonds bought by B in period 1. These bonds are bequeathed to C and finally paid off in period 3 by a tax levied onto C.

Result: A is better off at the expense of younger generation B.

Whoever bears the burden of the tax (which is ultimately what finances the transfer) loses. The only exceptions to this rule are when the growth rate of the economy exceeds the rate of interest to be paid on the bonds and when the bonds are handed down to the generation which bears the tax burden. In this latter case, the losers are those who value future generations so much as to give up present consumption for the benefit of those future generations and had the foresight to do so. They are forced into a situation where they have to make a decision offset the government dissaving or let future generations pay the price, a decision they would have preferred not to have to make.

As for the former case, if the growth rate of the economy is greater than or equal to the rate of interest on the bonds, then this Ponzi scheme could go on indefinitely. Here are a few considerations on this however. First, whoever purchases a government bond would most likely have been better had they just invested privately under these circumstances. Second, maintaining any debt creates a burden just by virtue of its existence. To make this clearer, consider if the borrowing in a period increased the debt to GDP ratio from 50% to 100%. The increase makes it more difficult and more expensive to borrow in the future, which wouldn’t be “fair” to a generation who can no longer employ deficit financing. Finally, does anyone actually think the perpetual borrowing described here is possible in practice or resembles anything in reality? Heck, is it even desirable?

old al only wins because he dies before being taxed, but no one else loses except the last old man on earth who has no one left to pay him.

everyone else does not lose. the people in the middle generations only don’t get a free lunch, like old al.

anon wrote:

old al only wins because he dies before being taxed, but no one else loses except the last old man on earth who has no one left to pay him.

everyone else does not lose. the people in the middle generations only don’t get a free lunch, like old al.

Nope, anon. You’re reasoning in terms of apples, but not utility from apple consumption.

Remember I’m using in this example the specific utility function U=sqrt(A1)+sqrt(A2). So the lifetime utility from the endowment is 10+10=20. In contrast, Bob, Christy, etc. only get sqrt(50) + sqrt(150) < 20 utils in this example, so they are all worse off. This isn't something sneaky, this is standard stuff. Most people would rather consume $100,000 of stuff in 2012 and $100,000 of stuff in 2013, rather than $50,000 of stuff in 2012 and $150,000 in 2013.

Bonds don’t buy future apples- they are oranges which represent a claim on future apples which may or may not go through.

You cant specify for a Utility function of the sort you are doing here.

Apples and oranges- old boy.

Or tell me why I’m wrong

Right, I’m not dealing with the possibility that the government could default; i.e. people treat a bond as an airtight claim to future apple consumption. That would add another layer of complexity, and we can’t even agree what’s going on in a case of total certainty.

You don’t need to assume people treat it as air-tight.

In a case of total certainty, we know that absent a Govt. there will be future trades. Present a redistributive Govt of the type you posit- not that it can succeed with this policy instrument in a deterministic manner- there will also be hedging against lump sum liability which, it is another weakness of your model, is impredicatively determined by bond uptake.

The crucial point you’re missing is that ‘apples aren’t the only fruit’. A hedge on apples is an orange. You can’t do subgame equilibria here. You can’t know Nash eqbm- why? You have no pref. rev. mechanism in your model. There is an information cost.

The whole thing is riddled with flaws.

Get rid of it or use it to show how Landsburg is more egregious yet and go back to the solid foundation of showing how there’s no fallacy of composition in saying unforeseen-ly high debt does too mean cut entitlements and raise taxes (on an analogy of a call on part paid Equity).

The most salient point here has to do with Agency Hazard. Preference falsification can give a popular basis for rent seeking Govts to fuck up the Economy on infeasible redistributive grounds.

Personally, I blame Landsburg ‘Reality Distortion zone’- his wierd reverse Talmudism- for turning you round on this issue.

Come back Bob. The kids miss you and Timmy the dog says woof!

if utility is greater in 2012, why does young bob lend 50 apples?

anon wrote:

if utility is greater in 2012, why does young bob lend 50 apples?

Good question, glad you asked so we can make sure everyone sees how this stuff works. Look at what happens in period 2. The government taxes Old Bob 50 apples. So, from Young Bob’s perspective in period 1, if he consumes his whole endowment (i.e. no loan to the government) then his consumption path will be (100, 50). But instead, he can lend 50 apples out of period 1’s income, so that in period 2, after taxes, he gets to consume 150.

So his choice is between apple consumption of (100, 50) or (50, 150). He gets more utils from the latter, which is why he voluntarily lends to the government.

Wrong! He applies for 100 apples worth of Govt bonds knowing he can sell at a profit.

Yield can’t be determined by the Govt. It has to depend on preferences.

The moment there’s a bond market you can’t stop every other type of inter temporal market.

For any given redistributive target in time t, a bond issue of that size will have random redistributional effects for this reason.

Indeed Old Bob could make a speculative loss greater than his transfer.

You don’t get that no rational Govt would use this policy instrument because the final outcome is non determinate.

The arguments for Utility functions are not as you assume- they can’t be because trading bonds can’t be constrained in the way you imagine.

Not unless you simply embrace outright Occassionalism.

vik, since–by my count–you’ve said at least 5 things about my model that are simply wrong, it would be nice if you would at least drop the condescending tone. For example, you keep talking about an informational asymmetry. But no, there is perfect certainty in this model right now; I’m trying to isolate the one thing Daniel Kuehn et al. aren’t seeing vis-a-vis my stance with Nick Rowe.

I assure you, no condescension was meant.

I am not interested in informational asymmetry because I don’t believe it has relevance in Public Finance.

Nor am I saying that there isn’t an axiom system for which your model isn’t concrete. That would be foolish.

What I have said is that your model is silly, or foolish, because we learn nothing interesting from it. On the contrary, it has encouraged you to do a filp flop and reverse your position from one of issuing a salutary warning against deficit financing in the name of Equity, to a faulty conclusion that deficit financing can improve Welfare. My point is that if itsnt deficit financing but letting a new economic good- viz hedging- come into existence that achieves this.

You are welcome to carry on trying to isolate the one thing on which you and certain others are equally but not identically wrong.

My fear is that far from providing any fundamental insight, isolating the point of contention between you may merely cement an already stonily unfruitful fidelity to a failed and irrelevant Research Program.

if young bob doesn’t lend, the government still taxes him and young christy? the governement now has a 100 apple surplus.

Yes, this is a point that I think was missed (by Landsberg perhaps?) previously: the saving or Ricardian equivalence in period 1 is itself coerced since it is made in reaction to the prospect of coerced tax payment in period 2. It is voluntary but only in the narrow sense that it is a voluntary choice from a coercively reduced set of options.

In fact, I am wondering whether this point alone is sufficient to demonstrate that everyone other than original recipient of the transfer is made worse off – i.e., they are all on the receiving end of a coercively reduced set of options.

Could not the government at any point decide not to do any more transfers by bond or by tax and immediatly return all future periods to maimum utility?

People from the past may get screwed but that doesn’t seem to be what we are discussing here.

One flaw is this.

If that first 50 apples are used to create new trees, then people are better off so long as the productivity of those trees are more than the cost of interest on the loans. [You’re missing that bit]

However, the problem is that governments by and large do not do investments that produce returns greater than the cost of servicing debts.

ie. Borrow at 5%, get growth of 2%.

Finally! I see someone mention the same kind of argument I made.

Your intuition is the same, but it’s tricky. It’s tricky because money is also the only produced commodity, so you have to kind of think like apples in the consumer goods sense and apples in the money sense.

You said so long as the productivity of those trees is more than the cost of the interest on the loans, then people are better off. But that is like saying X more apple trees in the consumer goods sense can be greater than 100 (or 50, depending on how you look at it) apple interest cost in the money sense.

In the real world where money is dollars and goods are, well like apples, then you can’t say 14 more trees is greater than $100 loan cost. They are incommensurable units. The only way they can be related to each other is through exchanges of each other, but that’s a tangent.

What should be compared, as you noted, is a world where the 50 apples are put into private investment for more apple production in the future, and a world where the 50 apples is borrowed and spent by the government.

I think what must be compared are the different apple productions in the two possible scenarios, which of course requires imagination since the world that exists is the 50 apples being loaned and then spent (which is why it is so hard to argue against positivists who insist that we only consider observable economic data as the only relevant economic information).

If the production of apples in the investment and production scenario is greater than the production of apples in the borrowing and spending scenario, then people are on net better off, assuming they value more apples to fewer apples.

Now, all is not lost, despite the fact that Austrians seemingly only rely on imagination and “dogma” concerning investment and consumption. We can know that because it is a priori true that the only way to boost production is by saving and investing more in production, and not consuming more output of production, that is a logical necessity that be used to refute those who insist that spending qua spending is what allegedly provides a foundation for economic growth, as if investment by profit and loss seeking entrepreneurs, and consumption spending by stewards, technocrats and bureaucrats, are economically identical in terms of generating economic prosperity.

People from the past may get screwed but that doesn’t seem to be what we are discussing here.

==============

It’s what’s going to happen.

As soon as the government makes a transfer via a bond or taxation then the only way that the individual affected can get his “share” of utility is if in the next period the govt does another transfer back to him.

If it does not do this though, he loses out.

My point is that it is clearly govt decisions in the present period that drive outcomes, not the carry over from transfers made in the past. The govt can cause an individual living in the present to fail to get his maximum endowment (by failing to do a make-up transfer to him for one he made in the past). It cannot however magically affect outcomes for anyone in the future – that can only be done by the govt at the time.

>My point is that it is clearly govt decisions in the present period that drive outcomes, not the carry over from transfers made in the past.

Step back for a second. Since you’re making a pretty crazy statement here, ask yourself how can the past have no bearing on the future when it comes to government activity through borrowing and spending?

Aren’t you ignoring what COULD have been produced or consumed, had there been no lending to a consuming entity that backstops its obligations by taxation?

” The govt can cause an individual living in the present to fail to get his maximum endowment (by failing to do a make-up transfer to him for one he made in the past). It cannot however magically affect outcomes for anyone in the future – that can only be done by the govt at the time.”

No, that’s wrong. The past actions of the government have created debt claims that for better or for worse, are treated and valued as a future cash flow and therefore an asset.

If the government taxes people to pay the debt back, then that is just an erasure of the debt claims, and total cash will remain the same. If people collectively have the same amount of cash, but fewer assets other than cash, then they incur a loss with no corresponding gain to anyone.

Stepping back even further, and extending the logic further, what you are saying is equivalent to saying that I cannot possibly lose out if I burned my own house down, because I did not build it in the past, I just own it now. After all, there is no way that the builder could possibly have affected me, someone who was not even born when he originally built the house!

You’re saying that the original home builder cannot possibly have had any affect on my life by virtue of him building the house before I was born. But that’s crazy. The whole nature of a growING, progressING economy, is that total wealth is growING on a foundation of current generations taking up ownership of capital that has been left to us by the previous generations, and thus the previous generations, for better or for worse, did affect the outcomes of you and I living today.

If this were not possible, then the human race would never have been able to escape caves (or the Garden of Eden, whatever floats your boat).

Daniel Kuehn, let me step back and try to save you and Major Freedom 16 hours of debate: Would you say, Daniel, that Krugman’s readers would think the following?

Proposition: If we assume lump sum taxes, a closed economy, etc. etc., then if the government keeps today’s spending constant but lowers taxes on the present generation–thereby increasing the “national debt”–then whether or not Ricardian Equivalence holds, it is physically impossible for this to make future generations of people collectively poorer. Sure, some individuals among our great-grandkids might be poorer, but it is an accounting impossibility for every single great-grandkid to be made poorer, because our great-grandkids will owe the debt to themselves, considered collectively as a whole generation. And to repeat, this holds whether or not Ricardian Equivalence is true, because this is simple accounting.

I personally think Krugman, Dean Baker, and Yglesias believe that. I believed it 3 weeks ago.

But now, as this particular numerical example shows, we see it is false. Government deficits today can indeed make every single person in all succeeding generations poorer.

So if that’s not “deficits burdening future generations,” I don’t know what would be. And, the burden emanates from the fact that future generations have to be taxed to service/retire the debt. This is exactly what the “naive” layperson worries about, and he is entirely right to worry. To point out to him, “Nah, our great-grandkids will owe the national debt to themselves” is utterly misleading. In my chart above, in period 7 (say), all of the government bonds are held by George. So the descendants “owe the apple debt to themselves,” and yet every single descendant of Old Al is made poorer because of his transfer payment in period 1.

Again, I’m not accusing Krugman et al. of being jerks, I’m accusing them of misleading their readers unintentionally. Those guys have no idea (I claim) that such a result is possible.

Bob,

I still think and want to emphasize that although you clearly showed that it is possible to spread the burden over several generations so that really all people are burdened after some or at least one generation that benefited, it doesn’t really change the point of the layman if the burden was put not on all but only on some people/generations in one or over several time periods. In reality I guess there will nearly always be people who are lucky or know how to play the political game that they are not among the burdened. (I am not taking into account here of effects of forgone private investment etc.. Only the different way people are burdened due to different government financing methods).

So the lesson from all this at least should be that this government financing method should be chosen which achieves that those generations in whose time period the benefit falls also the burden should fall as well. I guess this is hard to assess and even harder if not impossible to implement with our political and democratic system.

Although that is one of the possible outcomes, I don’t think that’s the real danger here. Maybe you are just presenting it this way to encourage certain people to think about it from your point of view.

The real danger is that you can have a whole string of consecutive generations where every single person is better off and only then after a significant length of time do we face the problem of making a generation worse off. Just going a fraction Buddhist on your good Christian ass; but “cause and effect” are the fundamental things that separate human thinking from nihilism, and the concept of Karma is the idea that cause and effect must always somehow loop back around and become one and the same thing (it’s theology so it doesn’t have to make literal sense).

Inter-generational debt allows cause and effect to be separated by many generations, enough to encourage people in the early generations to say, “there can’t possibly be a problem here,” while the people in later generations say, “Where did this come from? What did I do wrong here?”

Bob’s post appears to imply that once the govt has made the transfer from Bob to Al in period 1 then all the other transfers follow on as if pre-ordained.

All I’m saying is that if they defaulted on the debt in period 2 and decided that xfers were a bad idea then things would soon fix themselves and people would have maximum utility from their endowments for ever more.

Bob loses but everyone else gains:

As soon as a bond has been sold then someone in the future must lose (through taxation or default) but the govt in the present is the agent who decides if its in this period or pushed out further

(If the interest on an outstanding bond is high enough it may have no choice but to chose how the losses are distributed).

Rob, you’re right, there’s nothing set in stone for the future periods. In period 3 the people can revolt and default. However, that means half the people alive get screwed at that point.

The reason I did the above was to show that it is possible for every single person who lives after Old Al to be hurt by the deficit-financed transfer to him. I sincerely believe that Krugman et al. don’t realize this is even possible.

In this model in each period the govt has total power to distribute the endowments in any way they choose with no reference to the past or the future so one can get to any outcome they want.

If one tweaks the parameters a bit it gets even stranger. Change endowments so that they are not evenly distributed between the generations and it will “prove” that taxes are good. Does it even use cardinal utility to evaluate who the winners are ?.

I think the average Keynesian would love this stuff.

Rob. That’s not (I think) precisely correct.

If you tweak the parameters then everyone can gain from a debt financed transfer. But with those tweaked parameters, you don’t ever need taxes. Because the interest rate is less than the growth rate. So you can just rollover the debt forever.

Debt only hurts people if it causes increased taxes (or default, of course).

Nick,

I think in a model ,where the endowment if greater when young than old it can be shown that a tax from the young to the old is good.

You can also build a model where “everyone can gain from a debt financed transfer”.

Rob wrote:

In this model in each period the govt has total power to distribute the endowments in any way they choose with no reference to the past or the future so one can get to any outcome they want.

Rob, that’s dangerously close to the way Krugman et al. are looking at things. It makes it sound as if the people living in Period 1 can’t use the government to get richer at the expense of people living later.

So yes, what you’re saying is true, but I think a lot of people–myself included, as of 3 weeks ago–would have inferred something stronger from thinking about it like that.

Q: Can people living in Period 1 use the government to get richer at the expense of people living later within the constraints of the endowment OLG model

A: The govt can issue debt in a period that will transfer resources to some section of the population. Your model shows that following this initial transfer it is possible to carry out a series of subsequent transfers that leave all future generations worse off (as measured by the utility function) . However as there is no logical necessity in this sequence (they are just one choice amongst many others that would have led to different outcomes) I don’t think it can be said that there was a causal connection between the actions in period 1 that led to the enrichment and the subsequent generations when people had lower utility.

In the model as in the real world the government will be able to transfer resources wherever it wants to based on the priorities of the day. which will only to some extent depend upon commitments made in the past.

consider this:

http://coalbrook.com/drop/freezeDebt.png

(or more simply yours above)

al, bob, charles and dave’s lifetime consumption of apples is 210. after that starting with ed everyone consumes the regular 200 apples. Jeebus! Debt has made same generations better off and no future generation worse off (lifetime) and Nick Rowe and you are right it is as if apples have magically transferred from the future to the present! (a keynesian free lunch — not in the same way)

very disturbing.

but i don’t quite see this yet: “Government deficits today can indeed make every single person in all succeeding generations poorer.” in your previous examples one generation can be taxed and they are poorer, but every single generation? this is at least not necessarily true

Cato, in this particular example every single person is poorer. That’s why each person suffers lower utility; he can’t afford to buy the same stream of consumption as before.

I think to do this rigorously I would need to talk about the bond market more, so we would know how to evaluate people’s real income in the endowment case. I’d have to think about that a bit. But for sure, people can’t afford to buy the same consumption path in the above example as in the endowment scenario, because otherwise they would (and not lose utility). So they must be poorer, in terms of the market valuation of their (after-tax) lifetime income.

c8t0: I went through that idea and you get a perverse inventive. The early generations have the incentive to buy in (because there is genuine growth to be had). However, once it reaches a stable state, the later generations have the incentive to not buy in because they know they can’t actually benefit from the arrangement, so why “invest” money at what amounts to zero real return?

I don’t accept that it can reach a stable equilibrium, someone in the latter generations will say, “stuff this” and walk away.

Tel wrote:

I don’t accept that it can reach a stable equilibrium, someone in the latter generations will say, “stuff this” and walk away.

Tel, did you note the huge public support for defaulting on Treasury debt back in the summer?

A lot of Greek citizens seem to think that default is a sensible strategy. They might get to vote this February if anyone is interested… but regardless of who they vote for, I expect that a politician will win the election.

🙂

also its linear, cause i did this in my head, lousy monkey brain.

Here was my initial thought, when i did my first model:

There are 3 types of cohorts:

Early cohorts like my A, who get a transfer payment and no tax. those cohorts gain.

Middle cohorts like my B, who get neither transfer payment nor tax. They cannot lose (since they could revert to autarky if they wished) and will almost always (i.e. except for weird preferences) gain from intertemporal trade.

Later cohorts like my C, who get a tax, and who lose.

I really wish Paul Krugman and Dean Baker would say something. Daniel has been doing an absolutely sterling job arguing their position. At least, I wish they would say that there’s another way of looking at it.

PEOPLE, NOT TIME PERIODS, are what matter!

That depends on the question. Total output and consumption in a given time period does matter e.g. to determine potential GDP growth. in other words, even worse than putting a burden on future generations would it be to put a burden on them and leave them with reduced aggregates output at the same time.

Chris: Hmmm. I’m not really disagreeing with you. But I would say that GDP matters only because GDP (usually) affects people, and people matter.

Nick Rowe, I’m not sure if you’re getting my emails (are you?). Anyway, Alex Tabarrok said you and I should submit a paper on this somewhere. Is that worth pursuing? You know the state of the literature on this topic. I realize we wouldn’t be introducing the profession to the concept, but maybe a pedagogical article or something?

Bob: I got one email from you, earlier today.

I’m not sure if i know any literature at all, nowadays!

@bob murphy: re: “Cato, in this particular example every single person is poorer” i assume because of the sqrt utility function, otherwise in absolute terms they are richer. need to think about this more.

@nick rowe: “PEOPLE, NOT TIME PERIODS, are what matter!” precisely where i think the main disagreement lies between you guys and PK. krugman is probably (or should be) saying in no future time period is the current population of people worse off. but nick rowe is probably right in saying a generation is a person over time, not a population at one time. very interesting.

full disclosure: i must admit my brain has fluctuated between, “brilliant amazing insight” and “no, no, no something is horribly wrong.” =)

i’m going to stick with “hmmm..interesting”

You know, I think your example does highlight an interesting point I’d never thought of, though I can illustrate the same point in a simpler model without the OLG …..

The govt borrows from Bob to give to Abraham, figuring they’ll stick John with the bill several generations down the line. But Abraham cares about John, and would therefore like to undo what the govt has done. How does he do this?

Well, he can give his extra apples as a gift to young Bob; old Bob repays the favor by giving apples to young Christy, etc, right down the line. Which works unless someone in the middle of the dhain decides to keep the gift when young and not repay it when old, in which case John’s stuck with the bill again. So for Abraham to undo the damage to John, he’s got to rely on the good behavior of all the intervening generations.

But of course the same is true without the OLG. I’m fond of saying that if the govt gives me a tax cut, planning to stick my grandchildren with the bill, then I’ll just save the tax cut and restore my grandchildren to the status quo. But this doesn’t work if my children scoop up the inheritance and spend it before my grandchildren ever get to see it.

It’s an odd example because it assumes that people care more about distant generations than about nearby generations — but it’s still, I think, worth noting.

Steven is still premising his understanding of the our real world on fantastic knowledge & causal determinancy assumptions which aren’t true and can’t possibly be true of that world. (Rumsfeld unknown unknows and unknowable unknowns are unimaginable in the conceptual schemes Steven keeps imagining for us).”

Including the assumption that government can take stuff with a “given” value from the past, put them in a value extrusion machine, and then at a later time take that stuff and use that machine to extrude value “outputs” like a Krispy Creme machine extrudes donuts.

And what is actually happening in the actual world?

More and more resources are being re-distributed to retired government workers, on a borrowed dime — see how the education and public safety budget in Illinois & California is being swallowed by pension costs, funded by borrowing.

And government diverts resources and labor from higher output streams to uneconomical production processes like Solarus, which after economic failure actual require goods and labor to decommission, repurpose, or take to the dump.

The hypothetical without unknown unknowns, etc. is in the real world swamped by known realities.

How do we move value from the present to the future? How do we increase value across time?

We do it by having a skill for evaluating alternative constellations of production and by choosing longer production processes producing superior output over shorter processes producin inferior output.

Now, is government good at doing either of these things — if we substitute Congress & the bureaucracies of the gov for Steve Jobs etc, is the Congress going to do a better job? Are they going to choose the long term over the short term payoff?

That has to be plugged into your model, Steven, and instead all of it is excuded the demands of your logical construct.

If the gov borrows from you in order to give you a tax cut, the gov still has your money. You are ahead of the game only in the future, relative to everyone else. When you give part of your income stream to gov via lending the gov can now bid scarce production resources and labor away from you, the more incompetent gov is, the more uneconomics will be your own resource availabilities.

You will not be able to move resources across time as efficienty as you would have in the alternative world where you can manage the costs of government on a predictable tax schedule, and where you have to rely on your own skill to move resources into the future in competition with government bidders.

Yes, I understand this last thing needs shaping up.

you ought to add the sum of Sqrt’s Utility function to the post for people landing on just this page, in order to show why “every future generation is worse off”

SEL makes a nice point about a dependency in ricardian equivalence (where we assume RicEq and an otherwise perfect world) where you have shitty kids and reasonable grandchildren. =)

OLG plus Transfers from rich to old makes for interesting charts…awaiting PKs thoughts also.

Off topic a bit as usual, but hopefully there’s some linkage here…

I can’t help noticing similar themes popping up, but people don’t recognize that they are actually supporting the inter-generational debt model. Here’s an example:

http://money.cnn.com/2011/11/07/news/economy/wealth_gap_age/index.htm

Now check the graph of asset imbalance between the young and the old 1984 vs 2009. This is exactly what the model would predict as time goes on, there’s pressure on the imbalance between generations. Also, the 2008/2009 downturn was special because it was the first serious taste of debt unwinding that has been seen in several generations.

The other quote is from Zero Hedge w.r.t. China and their debt position:

And doesn’t that also fit the pattern? When push comes to shove, Sam comes round and puts a gun into Tabitha’s belly and says, “Time to pay now” and we can see that happening all around. Maybe I’m just seeing random events more in the line of this model because it happens to be what I’m thinking about right now, but they do seem related somehow. We now reach a brinkmanship battle where we see who really can force the next guy to pay up.