Old News: Murphy vs. Karl Smith

I just sent this to someone over email, to make sure he realized that I’m not a complete nutjob. If I ever debate Krugman, I will probably not make it shirts and skins.

Anyway, this was the online debate the Mises Academy hosted between Karl Smith (of Modeled Behavior) and me.

Clarification on Sumner, Congress, and NGDP

It is clear from the comments of my last post that, as usual, people are not fully appreciating the cogency of my analysis. Before diving in, let me make sure the casual reader understands why I’m spending so much time on this guy Scott Sumner, of whom most may never have heard. It’s not that Scott cheated me in a card game last summer or something like that. No, Scott is arguably the world’s leading advocate of “market monetarism,” which (in the present environment) leads to calls for bolder action by the Fed. Since I think this would be awful policy, I am trying to dismantle the Sumnerian worldview–some days, singlehandedly. It is an awesome responsibility. The fate of the dollar and Western civilization itself hangs in the balance.

Now in my last post, I criticized something Scott had said about Congress raising the minimum wage, and people were jumping up and down on me in the comments. I believe they have no leg to stand on. So let’s go through it more slowly. Here’s the relevant quote from Scott, to refresh our memories:

If [the natural rate of unemployment in the US] did rise to 8.1%, the most likely explanation is that the policies I mentioned above (minimum wage increase, extended UI [unemployment insurance], etc) caused the increase. But monetary stimulus would help on both fronts; reducing the real minimum wage (which never would have been passed had Congress know[n] how little NGDP growth we were going to get) and also causing Congress to reduce the maximum UI benefit more quickly, as they do after every previous recovery from a recession. [Emphasis changed.]

So let’s walk through my problems with this, and along the way I will answer my critics (i.e. Scott’s defenders).

(1) My fundamental problem with Scott’s entire approach is that he diagnoses economic problems in terms of NGDP. I don’t think that’s a helpful way to view the world. OK, we have that disagreement. But, if it’s bad enough that Scott himself walks around, thinking about economic problems in terms of NGDP, then it’s even worse if he starts attributing that perspective to everybody else. It is simply not true to say that Congress wouldn’t have done such-and-such if they known about NGDP growth. And to repeat, it’s not merely a harmless slip; Scott does this kind of thing a lot. To be clear: I don’t mind if Scott had said, “Congress had no idea how bad their move to raise the minimum wage would be, since NGDP was about to collapse.” But that’s not what he said, and he does this thing a lot–saying for example that firms enter into long-term contracts with certain expectations of NGDP growth, which they clearly do not.

(2) What’s even weirder about this whole thing is that Scott once argued that the Fed couldn’t have been responsible for a boom in the 1920s as the Austrians claim, because the monetary aggregates M1 and M2 hadn’t been defined at that point. (You think I’m putting words in his mouth? No, he said that.)

(3) I don’t think that when Congress passes a minimum wage increase, considerations of the economy come into play. I think it is a backroom deal to get votes from labor unions who benefit from making lower-skilled competition more expensive.

(4) Gene Callahan and others in the comments were arguing that all Sumner meant was, Congress wouldn’t have taken this measure had they realized how devastating it would be. Well hang on. An equivalent term for “NGDP” is “nominal income”. So let’s suppose it’s not purely a cynical, political move, and that some concern for economics is involved. You’re telling me that Barney Frank is thinking, “If I thought nominal income in this country would rise like it normally does, then I’d support a law forcing employers to pay poor people more. But, if I thought nominal income growth would stall, then I wouldn’t want to force employers to pay poor people more.” On the contrary, to the extent that they actually worried about the economy and impact on poor people, I think if anything they would do the opposite of what Scott says: They would jack up the minimum wage if they thought the market, left to its own devices, wouldn’t give rising incomes.

During the New Deal, the federal government implemented all sorts of policies that were explicitly designed to raise nominal incomes. Was this because nobody in the government realized the economy was bad in the mid-1930s? They erroneously thought NGDP growth had been brisk? No, I would argue (a) they didn’t care about the economy, these were political moves and/or (b) to the extent they cared, they thought raising incomes was a way to help people in an awful economy.

Question: If Gene (and Scott) are right, there should be examples of Congress cutting the minimum wage in response to a recession, right? Just like Congress might extend unemployment benefits and so on to help the laid-off workers, they should also cut the minimum wage once they see with their own eyes that NGDP growth has been too low. Has that ever happened? (Maybe it has; I’m genuinely asking.)

(5) Some people are trying to defend Scott by saying something like, “Look, Barney Frank knows you can’t raise the minimum wage to $1000/hour. That would be too high in comparison to the general price level. That’s all Scott was getting at.” Well, if that’s what Scott meant, then he’s in trouble. He has spent lots of posts arguing that what most people think of as problems with price inflation is actually due to NGDP. So I might be extremely generous and agree that in some vague sense, Congress agreed to hike the minimum wage because they were just trying to catch up with general price inflation, and maybe they wouldn’t have been so aggressive had they realized CPI growth would slow down for a few years. But, in that case, they would be directly contradicting several posts that Scott has written, saying why this perspective is totally wrong. Remember kids, on certain days of the week Scott bans the use of the word “inflation” on his blog because the very term leads to all sorts of nonsense.

More Evidence That Scott Sumner Is Out of Touch

Look kids, I’m as sick of the Sumner-bashing as you are. But it is apparently my duty, since nobody else is catching this stuff. If not me, who?

First of all, remember back when Garett Jones was talking about sticky prices and how he thought debt was a really good candidate for this? Then Sumner bit his head off (good-naturedly), and I was stunned because I had filed away that sticky nominal debt contracts played an integral role in the Sumnerian system? Well here’s Coach Sumner yesterday giving a pep talk to his team:

Nearly 4 years ago I and a few others started arguing that the crisis was being misdiagnosed by the economics establishment. Market monetarists argued that while banks did make some foolish loans, the deeper cause of the global financial crisis was a lack of nominal income; the resource that people, businesses, and governments have available for repaying nominal debts. The collapse in nominal income in the US and Europe was larger than anything since the 1930s, and hence most pundits and policymakers had no experience dealing with this situation.

It’s amazing how far we’ve come in less than 4 years. NGDP is the hottest idea in macroeconomics, and the lack of NGDP growth is seen as the root cause of the financial crisis. I recall in 2009 how commenters were incredulous when I said “NGDP,” not reckless banking, was behind the financial crisis. They thought I was crazy. Now it’s practically conventional wisdom. This means that all those “policy implications of 2008″ from both the left (who blamed the banks) and the right (who blamed the regulators) will have to be completely re-thought. It’s about time. [Bold added.]

I gave a longish quote to make sure you got the full context. Scott is clearly summarizing his worldview in a few sentences here. He doesn’t talk about sticky wages, no, he singles out nominal debts. Indeed, Krugman himself has argued that (moderately) flexible wages right now would actually make things worse, because of nominal debts. I don’t know if Scott endorses that particular argument from Krugman, but given the above, can you folks now I understand why I was astounded that Scott took Garett Jones out to the woodshed on citing sticky debt? Remember, it wasn’t simply that Scott said, “Well, I don’t think you described its influence properly…” No, he said if people owed a bunch of money, they’d go work harder. He made it sound like Garett had pointed to a factor that was the exact opposite of what the theorist needed here.

OK but now consider this gem. Today, Scott is trying to be open-minded and say that he acknowledges there are all sorts of real supply shocks to the system; he’s not simply saying it’s demand, stupid. Great, I’m on board. But then Scott casually says:

If [the natural rate of unemployment in the US] did rise to 8.1%, the most likely explanation is that the policies I mentioned above (minimum wage increase, extended UI [unemployment insurance], etc) caused the increase. But monetary stimulus would help on both fronts; reducing the real minimum wage (which never would have been passed had Congress know[n] how little NGDP growth we were going to get) and also causing Congress to reduce the maximum UI benefit more quickly, as they do after every previous recovery from a recession. [Emphasis changed.]

OK, do y’all see it? I’m being dead serious. Even you fans of Scott Sumner need to start preparing plans for the coup d’etat, once his insanity becomes intolerable. (Right now you must think it can be controlled, I guess.)

Scott is actually saying that the people in Congress only passed the increase in the minimum wage a few years ago, because they erroneously forecasted a higher NGDP growth rate than what we’ve in fact seen.

I have previously challenged Scott when he says stuff like, “Businesses signed contracts in 2007 assuming 5% NGDP growth,” on the grounds that I didn’t know what NGDP even meant in 2007, so I’m sure Joe the Plumber didn’t either, when borrowing against a line of credit with his wrenches as collateral. Scott replied that the market acts “as if” people make forecasts of NGDP. OK fine, it’s a harmless shortcut.

But does Scott really think Barney Frank was having a pow-wow with Charlie Rangel and some UAW bosses that went like this?

BARNEY FRANK: I’m going to push to raise the minimum wage 40%.

CHARLIE RANGEL: Are you sure? My Bayesian prior says there’s only a 38% probability that NGDP growth will average 5% over the next five years. We both know how devastating it was when NGDP collapsed in the Hoover Administration.

BARNEY FRANK: First of all Chuck, the proper metric is nominal wage growth, but I’m not going to have that argument with you again. In any event, my boys here from the UAW have created a synthetic NGDP futures contract that they trade in the cafeteria. Check out this PowerPoint show, I think you’ll end up co-sponsoring the bill with me.

P.S. I know some people are going to say, “Oh come on Murphy, cut the guy some slack. What he meant was…” By all means, tell me what he meant. I want to know in what universe the members of Congress raise the minimum wage after considerations of macroeconomics.

Inflation Is the Plan

I decide to go Bradley Manning on the economics profession. The world needs to know!

There’s Really Been a Lot of Real Shocks to the Economy

The venerable von Pepe sends me a good post by Larry White, who isn’t as sure as many of his colleagues that the world economy today is primarily troubled by inadequate demand:

Scott Sumner told us in September 2009 that “the real problem was nominal,” that is, the recession and its high unemployment were primarily due to an unsatisfied excess demand for money (combined with real effects on debt burdens of nominal income being below its previous path)….The price level had not yet adjusted enough to clear the market of unsold goods corresponding to deficient money balances. This was a reasonable – almost inescapable – diagnosis in 2009, when the price level and real income were both falling.

Market Monetarists who have been celebrating the Fed’s recent announcement of open-ended monetary expansion (“QE3′) seem to believe that Sumner’s 2009 diagnosis still applies. But what is the evidence for believing that there is still, three years later, an unsatisfied excess demand for money? Today (September 2012 over September 2011) real income is growing at around 2% per year, and the price index (GDP deflator) is rising at around 2%. If the evidence for thinking that there is still an unsatisfied excess demand for money is simply that we’re having a weak recovery, then as Eli Dourado has pointed out, this is assuming what needs to be proved….

While saluting Sumner 2009, like Dourado I favor an alternative view of 2012: the weak recovery today has more to do with difficulties of real adjustment. The nominal-problems-only diagnosis ignores real malinvestments during the housing boom that have permanently lowered our potential real GDP path. It also ignores the possibility that the “natural” rate of unemployment has been hiked by the extension of unemployment benefits. And it ignores the depressing effect of increased regime uncertainty.

To prefer 5% to the current 4% nominal GDP growth going forward, and a fortiori to ask for a burst of money creation to get us back to the previous 5% bubble path, is to ask for chronically higher monetary expansion and inflation that will do more harm than good.

This is great stuff, but I think even Larry isn’t doing it justice by simply pointing to “regime uncertainty.”

Let’s go back to my June 2009 article, “Why I Expect Serious Stagflation.” Now my critics can rightfully say that I was wrong about the magnitude of consumer price inflation. But let’s look at why I expected stagnation:

I am not going to be foolish and give annual rates of projected real GDP growth; let me simply summarize my view by saying that the economy will be in the toilet for a decade. (Consult another economics PhD for a precise translation of those terms.)

I really don’t understand how even some free-market analysts on CNBC and the like can talk about the recession ending this year, or who speculate that we’ve finally “hit rock bottom.” If they really believe that, then I wonder why they spend so much of their careers praising free markets and blasting socialism? If all of Bush’s and now Obama’s enormous interventions only yield a few quarters of a moderately bad recession, then what’s all the fuss about?

We have all been desensitized to the federal power grabs, because they have been so sudden and so sweeping. The human mind is able to adapt to any new environment fairly quickly.

Let’s think back just one year ago. Remember when plenty of people were worried about the “unjustified” intrusion of the Federal Reserve into the Bear Stearns takeover? Contrast that to today, when the federal government is literally acquiring outright, common-stock ownership in major banks, where the precise accounting mechanism is a conversion of (TARP) “loans” that it forced some of these banks to take, and which the government (as of this writing) refuses to allow to be paid back.

Or how about this one: in the spring of 2008, the Bush administration pushed through a stimulus tax cut that cost a little more than $150 billion. Do you remember that at the time, this was considered a fantastic sum of money? Analysts on CNBC fretted about the impact on the deficit and interest rates.

Well President Obama’s stimulus package was $787 billion; the expected federal deficit this fiscal year is $1.8 trillion. The CBO projects that the federal debt as a share of the economy will doubleover the next decade, from about 41% last year to 82% by 2019.

Beyond the massive shift of resources to the government, though, are the massive intrusions of federal power into various sectors. The feds have already partially nationalized the banking sector (a process started under that “laissez-faire conservative” George Bush); they have taken over one of the biggest insurers in the world (AIG) and two of the Big Three car companies; and they have taken over Fannie and Freddie and now control more than half of US mortgages.

On top of that, they are pushing through a plan to cap carbon-dioxide emissions — which allows the government to control energy markets, and — oh why not? — they are trying to nationalize health care too. Just to make sure investors around the world stay clear of the American economy, the Obama administration has overturned secured-creditor rights in the Chrysler fiasco and has hired 800 new IRS employees to put the screws to wealthy filers with international business operations.

It is no exaggeration to say that the last time the government expanded this much, this quickly, was under FDR’s New Deal. And we got a decade of misery during that particular experiment. Why would things be different this time?

Let me put it this way: Suppose there had never been a recession. Suppose that for some reason, in the fall of 2008 the Fed took over Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and AIG. Then Henry Paulson convinced the free-marketeer George Bush to inject $700 billion into major banks and car companies in order to gain serious leverage over their decisions, even though some of them didn’t want the money. Then a few months later, the incoming president announced a $787 billion package of poorly-designed (from an supply-side POV) tax cuts and pork barrel spending, including a bunch of money going to renewable energy companies that would later go bankrupt.

What would free market economists have said at the time? Would we have said, “Eh, a budget deficit of 10 percent of GDP is a bad idea, but no biggie”?

No, we would have been flipping out, warning of how much damage these obscene and arguably fascist measures would do to the economy. And that would have been with a healthy economy.

So why is it such a shock (no pun intended) that some of us think maybe the US economy isn’t suffering from too much saving in the last few years? Maybe this incredible surge in federal power has something to do with it?

And–if I might be even bolder–maybe all of the crazy things FDR did under the New Deal explain the length of the Great Depression, as opposed to “tight money” (even though the US went off gold in 1933, and we never had a depression as long under the gold standard as we did after we went off it).

The Fatal Conceit

[UPDATE below.]

The title of this post refers, of course, to Hayek’s warning about really smart guys thinking they understand a complex system well enough to start tinkering with it. Nick Rowe has had the generosity (and intrepidity) to hang out in the comments of my post criticizing his optimism over QE3. He told me he didn’t really understand what I was driving at, especially since the two of us agreed on what (Nick claimed) was the sole point of his post.

As Obama would say, let me be clear: I am saying that guys like Paul Krugman, Scott Sumner, Nick Rowe, and (so help us) Matt Yglesias think they understand the global economy well enough to say that the Fed buying another $40 billion per month of MBS until it works, is a “step in the right direction” or evidence that “we’re winning.” Yet their models are incredibly crude. The only reason they don’t understand how problematic this is, is that they spend most of their time talking to each other. Paul Krugman actually spends a lot of time bragging about how much you can learn about fighting this crisis from studying a chart of two lines intersecting each other, and Nick actually wrote the following, thinking it was a slam-dunk against (some of) the people opposing more monetary stimulus:

Even suppose the financial system totally collapsed. Why should that prevent monetary and fiscal policy working to increase demand? The biggest flaw of orthodox macroeconomic models is that they have no financial sector. So, if the financial system disappeared, that ought to mean those models would work even better.

Now look, I understand “what Nick meant by that.” He is making a very specific point to a subset of analysts who (a) agree with him that a shortfall of generic aggregate demand is “the problem” and (b) doubt that more QE will help on this front. What I am saying, however, is that if you find yourself typing out the above statements, you should pause before being so sure that creating another $40 billion per month–indefinitely–in propping up the housing market is a good idea.

There are lots of areas of scientific inquiry where the experts involved simply don’t understand the phenomenon very well. If, say, some physicists approached Congress and asked for $40 billion per month to fund the development of a cold fusion reactor, and Congress said, “How much total money do you need?” and they said, “Until we get it right,” that would be alarming. Especially if they admitted their models didn’t include electrons because that took up too much computing time.

Notice in this scenario, that these physicists could still be the world’s experts on the processes involved. The critics in Congress and the public who thought the $40 billion monthly funding wasn’t justified, wouldn’t have to prove they knew the physics better, nor would they have to perform better on a prediction of how subatomic particles would behave in experiments 6 months prior to the funding request. We could still imagine circumstances in which it would be perfectly correct, “rational,” and “scientific” to tell the physicists and engineers, “You guys are all really smart, you have done pioneering work in these fields, but sorry, we just don’t feel you understand Nature enough to get this kind of funding right now. We have seen you guys arguing with each other, and it’s not pretty. We’re not at all convinced that you have an adequate handle on this to justify what you’re asking.”

So I claim we have something similar with mainstream macro and monetary economists right now.

UPDATE: As always, Blackadder tries to keep me honest in the comments. His caustic barb reminded me of something I meant to say in the original post: I now believe more than ever, that if someone made me Fed chief, the proper thing to do would be to resign. Libertarians often say that type of thing in Q&A sessions, and it’s partly to be funny I suppose, but in reality it’s the right answer: There is no “proper” way to run a central bank. Even in terms of shutting it down, it’s really hard to start writing on this topic without just making stuff up. For example, Carlos Lara and I had a proposal (deep into this book) for going back to gold money and free-market banking (not to be confused with “free banking” necessarily), but it involved some arbitrary features. After reading Mises’ proposal (which also was “second best”) I realized he had thought of some things we hadn’t.

What I am saying is, I would like to think if I actually were offered the option of scaling back (but not eliminating) the government’s influence over the monetary and banking sector, that I would have the wisdom and courage to throw the ring of power back. The virtue of the Austrian School is that it understands the limits of our ability to predict what will happen in something as complex as the global economy. We think we have a qualitative understanding of how market forces work to correct disequilibria, but the claim really isn’t that “our model is better at prediction than the Keynesian ones.”

Quibbling With Chesterton

I’m reading (and loving) G.K. Chesterton’s Heretics. But in his essay on Bernard Shaw, Chesterton ends with a passage that seems a bit off to me:

Mr. Shaw cannot understand that the thing which is valuable and lovable in our eyes is man–the old beer-drinking, creed-making, fighting, failing, sensual, respectable man. And the things that have been founded on this creature immortally remain; the things that have been founded on the fancy of the Superman have died with the dying civilizations which alone have given them birth. When Christ at a symbolic moment was establishing His great society, He chose for its corner-stone neither the brilliant Paul nor the mystic John, but a shuffler, a snob a coward–in a word, a man. And upon this rock He has built His Church, and the gates of Hell have not prevailed against it. All the empires and the kingdoms have failed, because of this inherent and continual weakness, that they were founded by strong men and upon strong men. But this one thing, the historic Christian Church, was founded on a weak man, and for that reason it is indestructible. For no chain is stronger than its weakest link.

For the most part, I love what Chesterton is saying here. However, I think it’s too hard on Peter and too easy on Paul and John. Yes, Peter is a man, but so were Paul and John. Paul’s claim to fame is that he literally persecuted Christians before Jesus made the scales fall from his eyes. Paul wasn’t being falsely modest when he said he was the worst sinner of all. I know some Christians like to say Paul was just being a role model for us there, but no, I think he actually believed that. Precisely because of the mental faculties and training in the Jewish Law with which God had blessed him, it was unconscionable that Paul should’ve missed who Jesus was initially. I definitely would understand if Paul thought his error was far more scandalous than what Pontius Pilate had done.

As far John, I was always amazed that he had his followers ask Jesus if He were the Messiah, or if they waited for another. John recognized the Lord in his presence as a fetus. Yet the grown man, supposedly in close communion with God, and despite God the Father Himself saying, “This is my beloved Son” after John baptized Jesus, still apparently had doubts when he was languishing in prison.

But back to Peter: Chesterton is making it sound as if Jesus picked the worst possible guy, just to make sure the system couldn’t be toppled by an even bigger clown down the road. But no, I don’t think that’s true at all. Jesus picked Peter because he was a rock. Neither John nor Paul were rocks. Yes, Peter denied Jesus three times, but the only reason he was in the position to do so, was that he followed Jesus (after declaring that he would die for Him). Nobody else was there to deny that they were Jesus’ disciples, because they had fled in terror after the arrest.

Jesus didn’t just grab some random person, nor did He seek out the weakest link, when He approached Peter and his brother who were fishing at the time, and said, “Follow me, and I will make you fishers of men.” For one thing, that invitation/command itself wouldn’t have worked on just anybody.

Nick Rowe Is Going to Excommunicate Me

Wow. I have been immersing myself in the monetary economics blogosphere discussions, and I don’t likes what I sees. In this post I’ll talk about Nick Rowe, whom you may recall I previously dubbed a kung fu master.

As with Scott Sumner, so too with Nick: I want to preface this post by saying he’s a funny guy, very smart, and a good economist. But when it comes to monetary policy, it’s not merely that I disagree with him, it’s that I am shocked by the words coming out of his keyboard.

In light of QE3, Nick was relieved that the tide had turned and put up a post saying, “We’re winning.” To show how much better things were now, Nick linked his readers to a post he had made in May 2010. It is this older post from which I want to quote, because it really should terrify the average Joe. So here’s Nick Rowe from a little more than two years ago, lamenting the state of the macroeconomics profession:

I think we are witnessing the biggest silent shift in macroeconomic thought since the Second World War. For 70 years we have taught, and believed, that we would never again need to suffer a persistent shortage of demand. We promised ourselves the 1930’s were behind us. We knew how to increase demand, and would do it if we needed to.

The orthodox have lost faith in that promise; only the heterodox still believe it. And the heterodox have nothing in common, except for keeping the faith.

The orthodox haven’t lost hope. They hope that monetary and fiscal policy will be enough to get us out of this recession, and that the limits on monetary and fiscal policy will not be binding this time around. And they are probably right. But they have lost faith that monetary and/or fiscal policy will always be enough – that there are no limits.

And if the Eurozone too turns Japanese, they may start to lose even that hope.

There are two types of macroeconomist.

The first says “What do you mean you can’t increase aggregate demand? You run out of paper? Ink? You scared of inflation?”

The second says “But monetary policy won’t work at the zero lower bound. And there are limits on fiscal policy, because we daren’t let the national debt get too big.”

Scott Sumner and Modern Monetary Theorists are examples of the first type of macroeconomist. They have nothing in common, except that one thing. But that one thing is more important than all their differences. And they are heterodox.

Traditional Keynesians and monetarists, the competing schools of the old orthodoxy, belonged to the first type of macroeconomist. They differed only on tactics. They kept the faith. But they have now gone, and only monetary cranks sing the old religion.

The second type of macroeconomist represents the new orthodoxy. Few orthodox macroeconomists today will admit point-blank to having lost the faith, any more than a bishop, no matter how liberal, will admit to being an atheist. But if you believe that monetary policy is ineffective at the zero bound, and that there are limits to how long you can have a big fiscal deficit, it comes to the same thing. You have lost faith that you can always and everywhere increase demand by whatever it takes for as long as is needed.

Losing faith in monetary and fiscal policy, the orthodox turn to financial policy. “If we had better regulation and/or supervision of financial markets and institutions, we wouldn’t have gotten into this mess in the first place”. That’s probably true, but it’s also a distraction from the loss of faith. Financial markets and institutions are inherently unstable. They borrow short and lend long; they borrow safe and lend risky; they borrow liquid and lend illiquid; they borrow simple and they lend complex. Finance is magic; you know it can’t really be done. Regulation and supervision can never eliminate financial instability. If your faith is contingent on being able to prevent financial crises, you have lost the faith.

Good financial regulation and supervision are important in their own right. A good financial system will better serve the interests of borrowers and lenders. It will create benefits on the supply side. And financial crises will almost certainly cause demand to fall. But just because something causes demand to fall doesn’t mean monetary and fiscal policy can’t work. The whole point of Keynesian policy was that when (not if) something did cause demand to fall, monetary or fiscal policy could and should be used to increase it back again.

OK, and now that you’re warmed up, Nick follows the above with what must be one of the most unintentionally damning indictments of his whole worldview ever written:

Even suppose the financial system totally collapsed. Why should that prevent monetary and fiscal policy working to increase demand? The biggest flaw of orthodox macroeconomic models is that they have no financial sector. So, if the financial system disappeared, that ought to mean those models would work even better.

We’re kind of at the point where my commentary on the above is superfluous. If you read all that and are nodding your head saying, “Yes, yes, I like what you’ve done here, Nick,” then my criticism will seem crude and irrelevant to you. If, on the other hand, you’re reading that and thinking, “Wait a second. He doesn’t think there are limits to monetary and fiscal policy, even in principle? What exactly does he mean by that? And he’s using the fact that his models don’t have financial sectors as further evidence that we ought to be trusting them right now? Huh?!” then you don’t need me to spell out the problems here.

So instead of me criticizing Nick, let me be a nice guy and give my own explanation of what happened. In his latest post (which I link above but from which I’m not quoting), Nick is happy but baffled as to why his pessimism of May 2010 is now turned back to optimism. In other words, Nick can’t understand why so many of his peers lost the faith in the first two years of this crisis, but now they seem to have it back all of a sudden. Here’s my take:

==> Although there were a few Cassandras (including Nouriel Roubini from the interventionist side and Peter Schiff from the hard-money/deregulate side) who had very prescient descriptions of what was coming, generally speaking most economists had no idea just how bad things would be in 2008.

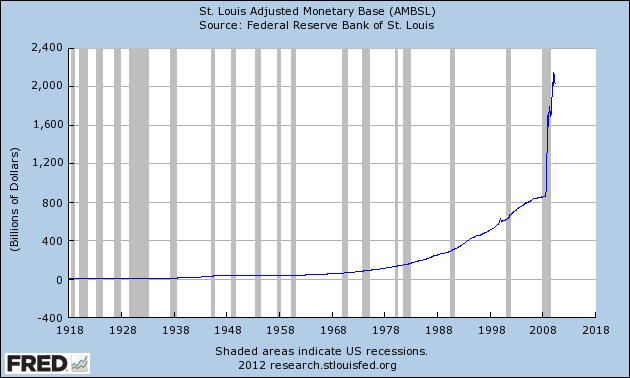

==> Even though most economists taught and published on the academic models that form the core of Nick’s religion (hey, I’m just continuing his metaphor), they didn’t believe it in their bones. They actually had common sense, and realized that this type of picture was scary:

The above picture isn’t the current one; it shows what the monetary base looked like, as of May 2010. So I’m saying I think most economists had common sense, looked at that chart, and thought, “You know, I just can’t agree with Scott Sumner that that is a picture of the tightest monetary policy since Herbert Hoover. I understand how back in the Depression, M1 and M2 actually fell sharply, and so did prices. But we’ve had rising Ms and CPI since the start of 2009. Sure, CPI growth hasn’t been high by historical standards, but we haven’t had outright deflation. And man, the Fed sure has pumped in a lot of base money. Maybe pushing harder on that particular lever isn’t really the answer. I’m not even sure running up more government debt will help, since we’ve had multiple years of trillion-dollar-plus deficits and that too doesn’t seem to be working very well.”

==> So why the turnaround? I think it’s because guys like Peter Schiff, Marc Faber, and (to a much lesser extent, since I’m not famous) me, were going nuts in 2009 warning everybody about Bernanke’s mad plan to debase the dollar. When our warnings didn’t come to pass, Krugman and Sumner (mostly Krugman) were running victory laps, saying “nana nana boo boo, we were right and the critics are idiots.”

==> Seeing that unprecedented money-creation didn’t seem to hurt, economists slowly got convinced to give it another try. In this effort, guys like Sumner were instrumental, because he relentlessly used very cogent arguments and data to show why everything made sense, from his perspective.

Recent Comments