Intelligent Design Is a Scientific Theory, So Long as God Isn’t Invoked

A recent news item in the Huffington Post caught my attention:

Scientists in the U.K. have examined a tiny metal circular object, and are suggesting it might be a micro-organism deliberately sent by extraterrestrials to create life on Earth.

…

The University of Buckingham reports that the minuscule metal globe was discovered by astrobiologist Milton Wainwright and a team of researchers who examined dust and minute matter gathered by a high-flying balloon in Earth’s stratosphere.

“It is a ball about the width of a human hair, which has filamentous life on the outside and a gooey biological material oozing from its centre,” Wainwright said, according toExpress.co.uk.

“One theory is it was sent to Earth by some unknown civilization in order to continue seeding the planet with life,” Wainwright hypothesizes.

That theory comes from a Nobel Prize winner.

“This seeming piece of science fiction — called ‘directed panspermia’ — would probably not be taken seriously by any scientist were it not for the fact that it was very seriously suggested by the Nobel Prize winner of DNA fame, Francis Crick,” said Wainwright.

Panspermia is a theory that suggests life spreads across the known physical universe, hitchhiking on comets or meteorites.

The idea of directed panspermia was suggested by Crick, a molecular biologist, who was the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA in 1953. Twenty years later, Crick co-wrote — with biochemist Leslie Orgel — a scientific paper about directed panspermia.

…

Even with this more recent discovery of a tiny globe found lodged into a high-flying balloon, the alien space seed proponents know they have a long way to go before that can be proven and accepted by the scientific community.

“Unless, of course, we can find details of the civilization that is supposed to have sent it in this respect, it is probably an unprovable theory,” Wainwright conceded.

Time — and space — will tell.

I have not spent any more time investigating this particular theory than what it took me to read the article and copy it here. My guess is that aliens were not involved with the miniscule metal globe.

However, the reason I’m posting this article on my Sunday religious post is what the article did NOT say: Namely, the very idea of suggesting that a biological object was designed by an intelligence is ipso facto unscientific. And yet, we hear that all the time in standard discussions of “Intelligent Design.”

This is a point that I would repeatedly make when hearing a biologist tell me ID was an unscientific theory. I would point out that it’s theoretically possible that aliens seeded life here on Earth billions of years ago, with an initial cell or cells that were truly “irreducibly complex” in the ID sense of that term. This wouldn’t prove that the Christian God created the aliens in 6 days; perhaps the aliens’ own cells evolved in the textbook neo-Darwinian way from inorganic molecules. But the point is, if scientists looked at the aliens’ cells and the ones on Earth, it’s possible that the terrestrial ones would be irreducibly complex whereas the aliens’ cells could have plausibly arisen through step-by-step mutations.

To repeat, I’m not saying that the above is plausible, and I’m not (for the purposes of this argument) taking a stand on whether terrestrial cells are irreducibly complex, in the ID sense. My point is a methodological one: Surely the question of whether my scenario is plausible or not is an empirical one. Biologists and other scientists would actually have to look at terrestrial cells under the microscope, and come up with various theories about how they could have arisen from the primordial soup on Earth billions of years ago. Surely it wouldn’t do to say, “It would lie outside the scope of science to wonder whether these organisms were deliberately designed. We have to proceed on the assumption that all organisms on Earth arose in a blind process, because otherwise we are doing the equivalent of explaining thunder by reference to angry gods.”

It is theoretically possible that life was seeded on Earth by intelligent beings (or a single Being) who did not come from Earth. Surely scientists have a lot to say on this question. To rule out this hypothesis from the get-go would itself be incredibly unscientific and a violation of empiricism.

A Sincere Question for the “We Owe It to Ourselves” Camp

David Stockman links to this old Krugman column on debt burdens. Here’s the key part of the article:

Deficit-worriers portray a future in which we’re impoverished by the need to pay back money we’ve been borrowing. They see America as being like a family that took out too large a mortgage, and will have a hard time making the monthly payments.

This is, however, a really bad analogy in at least two ways.

First, families have to pay back their debt. Governments don’t — all they need to do is ensure that debt grows more slowly than their tax base…

Second — and this is the point almost nobody seems to get — an over-borrowed family owes money to someone else; U.S. debt is, to a large extent, money we owe to ourselves.

This was clearly true of the debt incurred to win World War II. Taxpayers were on the hook for a debt that was significantly bigger, as a percentage of G.D.P., than debt today; but that debt was also owned by taxpayers, such as all the people who bought savings bonds. So the debt didn’t make postwar America poorer.

Now some of you–I’m especially thinking of Daniel Kuehn and “Lord Keynes” if he swoops in–think this is great stuff, and that Krugman is making a very important point here that clarifies the typical discussions of fiscal policy. So my question: Why do governments issue savings bonds to their own citizens during wars?

To be sure, a Krugmanite would totally understand why a government in a wartime crisis would issue bonds to foreign capitalists in order to suck outside real resources into the country. But why–using the “we owe it to ourselves” mentality–would a government decide to finance a war through bonds issued to its own citizens, rather than levying higher taxes? Either way, the people alive “pay for” the war effort, right? The next generation as a whole is totally indifferent to whether they inherit $0 in government bonds or $1 trillion in government bonds, right? The level of the debt they inherit just affects the volume of the transfer payments among them, but can’t make the next generation poorer, right?

So to repeat, explain to me in a Krugmanite framework why governments historically resort to debt financing when they’re in a major war, even among their own citizens.

Reading List for Debt Burden Stuff

Roger Farmer gives a good list here, though most of the papers are formal and would be hard for a non-academic to read. However, it shows the extensive history in the literature of this stuff.

Roger linked to this piece I did in the American Conservative, which I had totally forgotten. It is now going to be my go-to piece for a plain English version of my take on this controversy; if you still haven’t had it “click” for you, you might give it a try. I’m going to give a lengthy excerpt here because I think this is the best (plain English) example I had come up with. (BTW I’m working on a new article but it might not come out for a while.)

Suppose the government today borrows an extra $100 billion in order to expand drug coverage for seniors. Assume that the young workers today “pay for it” in the direct sense that they reduce their consumption by $100 billion, in order to invest in the additional $100 billion in government debt that has to be issued. (Thus, we are assuming unrealistically, for the sake of argument, that the higher government debt doesn’t “crowd out” private investment, just so we can see quite clearly why Baker and Krugman are wrong on this issue.) Clearly the older folks are better off because of this deal: they get more drug coverage from government spending, and don’t have to pay higher taxes to finance it.

Now further suppose that the young workers don’t touch their bonds, which happened to be 30-year Treasury securities rolling over at (say) 3 percent. After 29 years have passed, the originally young workers are now old. The original seniors—the ones who benefited from the $100 billion in extra drug coverage—are long dead. A new group of workers—who weren’t even alive when the $100 billion was borrowed—are now on the scene.

The now-old retirees sell their 29-year-old bonds at their current market value of $236 billion (that’s the original $100 billion compounding at 3 percent annually for 29 years in a row). At this point, the middle generation—the ones who were young workers originally, and now are retiring and living off of their savings—have been made whole. Yes, they reduced their consumption by $100 billion back when the government ran a budget deficit, but at the time they voluntarily lent that $100 billion to the government, because they thought getting $236 billion in 29 years when they were retiring would make the whole deal worthwhile. They didn’t lose from the whole operation.

Finally, suppose that the young workers (who were recently born) hold on to their government bonds for one more year, when they mature with a market value of $243 billion. In order to pay off the bonds, the government imposes a one-time surtax on current workers of exactly $243 billion. It thus takes the money out of the workers’ paychecks, and then hands it right back to them to redeem the 30-year bonds that they are holding.

The way Dean Baker and Paul Krugman have been “educating” their readers since late 2011 on this issue, they would be forced to argue that in our story above, the young workers weren’t hurt by the original $100 billion borrow-and-spend scheme. After all, the government 30 years later simply took $243 billion from those workers, and then gave it right back to them. So clearly it’s a wash, right?

But we can see it obviously wasn’t a wash. The original, old generation benefited greatly, the middle generation did all right, and the young generation—not even alive at the time of the original $100 billion deficit—got skewered. Yes, they “owed the federal debt to themselves,” but that is hardly consolation to them. Theyacquired the bonds by reducing their consumption by $236 billion the year before the big tax bill hit. This abstinence was not rewarded with additional consumption at some future point, but instead was necessary just to break even after the government whacked them with a big tax bill to retire its exponentially rising debt.

As this short tale illustrated, the man on the street’s intuition is correct: today’s budget deficits can impoverish future generations, even if future Americans hold all of the Treasury bonds. There really is a sense in which voters today can run up the credit card and stick the bill to unborn future generations.

Krugman Defenders 0, Murphy/Rowe 324

When the nutty Irishmen continue to roll their eyes at Nick Rowe on the debt burden stuff, it would be nice if they didn’t keep committing the same fallacy that Krugman did on Day One of this debate. (Here’s Gene telling Nick that the debt can’t burden future generations because they will inherit the bonds–meaning at that moment, there had been literally zero progress in the debate, even though Gene continues to assure us that he totally gets the obvious little point Nick keeps making.)

The other culprit is Kevin Donoghue, who also assures us he totally gets the obvious overlapping generations stuff, and says that Krugman gets it too–it’s too stupid to even bother mentioning out loud, which is why Krugman has ignored Nick all these years.

And yet, in another of Nick’s posts, Kevin writes this:

Nick, I just took another look at SWL’s “Redistribution between generations” post (link below). I don’t believe Krugman would dispute anything there, or that anything he’s ever written was meant to imply that government debt never involves redistribution between generations. But what comes through very clearly in that SWL post is that there must be a *change* in transfers between the old and the young if that latter are to be ripped off. The level of debt is irrelevant in that context.

Krugman is mostly concerned with refuting people who think that even a closed economy with $10k of debt per person must be more heavily burdened than one with $1k debt, even if the debt is rolled over. It’s quite a different topic.

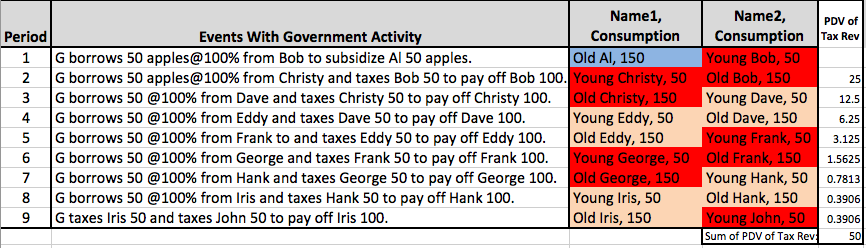

OK, I am going to now give a simple numerical example–of the same flavor that Nick and I have been cranking out for three years now–to show that the above is totally wrong. Here goes, with my explanation following:

In the model above, there are always 200 apples harvested every period; real GDP is always 200 apples. Taxes do not impose any deadweight losses. It is a pure endowment economy; there is no physical investment or depreciation of capital. Each person has a lifetime utility function of SQRT(c1) + SQRT (c2), that is, you take the square root of the apples consumed in the first period and add the square root of the apples consumed in the second period. There is no discount on future utility per se.

Now what happens in the above scenario is that in period 1, the government borrows 50 apples from Bob and makes a transfer payment to Al. There are no taxes, so the deficit is 50 apples and the government’s debt goes from 0 to 50 apples.

Then from periods 2 through 8, the government rolls over the bonds. It taxes the public just enough each period to cover the interest on the debt, which stays fixed at 50 apples, i.e. 25% of GDP.

You can check that (a) Dave through George are worse off compared to a situation in which they consumed 100,100 and (b) Dave through George voluntarily lend the government 50 apples when young in order to get 100 apples paid back when old. Make sure you realize that each individual thinks his future tax burden is given, and then he voluntarily decides whether to lend to the government at a 100% real interest rate.

Thus, Dave through George are hurt, relative to a no-debt scenario, even though the debt is rolled over during these years. Obviously, if the original deficit had only been 1 apple, the burden on them from carrying it would have been lower. I encourage you to go re-read Kevin’s comments quoted at the beginning of this post. It sure seems like he is definitively saying that if we are in years where the debt is merely rolled over, then the people in those years aren’t affected (in the aggregate) by the level of the debt. The example above shows that that isn’t true.

Now at this point, it wouldn’t surprise me if Kevin or Gene or Daniel Kuehn said, “Right Bob, that’s what we’ve been saying for years” but somehow their comments keep suggesting otherwise. At the very least, someone who just read Krugman on this stuff would have absolutely no idea that the above scenario was physically possible.

Potpourri

==> Mark Spitznagel doesn’t believe in “black swans” when it comes to market crashes.

==> Christopher Goins in the American Spectator talks to Mark Thornton about the Fed.

==> Remember that lady who lost her job when she tweeted about AIDS and Africa? Turns out she was being ironic. (At the time I thought it was absurd for her career to be ruined over a dumb joke, but she was being ironic with the joke, something I hadn’t realized.)

==> Nick Rowe (here and here) continues trying to illustrate the debt burden thing. In the comments, Kevin Donoghue illustrates that it is impossible to guide those who do not realize they are blind.

Rand Paul Criticizes Fed, Pundits Flip Out

My latest at Mises CA. The conclusion:

Despite the minor mistakes in his presentation–which again was from a speech to a live audience–Rand Paul has put his finger on a very serious issue. Central banks around the world have loaded up on assets, particularly central government debt, in an unprecedented fashion. If and when they decide to raise interest rates, among other things such action could instantly render the major central banks insolvent. Not only would this possibly cause a worldwide financial crash, but it would also limit the central banks’ ability to reduce the quantities of fiat money. No doubt they would continue to operate, much as the banker in the board game Monopoly when he runs out of money, but that still doesn’t justify the situation economically. There’s a reason bankrupt firms stop operating in a genuine market economy.

Another Post on Government Debt, but Krugman Made Me Do It

An excerpt:

To illustrate the situation, permit me a silly analogy. Imagine you saw the following debate among economists:

KRUGMAN: People are always yelping about the dangers of guns, but so long as people wear bulletproof vests, they can’t possible be hurt by gunfire.

ROWE and MURPHY: What the heck is he talking about?! Imagine a guy wearing a bulletproof vest, and someone else walks up and shoots him in the head. Uh, try again Krugman.

LANDSBURG and CALLAHAN: Well Krugman is right, if you think about it. A gunshot to the head doesn’t necessarily harm someone; we can imagine a guy with a scorpion on his head, and the bullet just nicks him while taking out the scorpion. Furthermore, we can achieve the same result of killing a man with head trauma by, say, smacking his temple with a hammer. So Rowe and Murphy are wrong to think that gunfire per se causes death from head injury.

KRUGMAN: Like I’ve been saying for years, nobody understands guns. Let me say it slowly, everyone: If you’re wearing a bulletproof vest, a bullet can’t hurt you.

LANDSBURG and CALLAHAN. Beautiful, Paul. Preach it brother.

Again, I realize the above is a bit silly, but then again I can’t believe Krugman is still getting away with titling posts, “We Owe It to Ourselves.”

Recent Comments