Potpourri

==> This podcast was not nearly as sultry as the image suggests.

==> Ron Paul responds to Paul Krugman’s “Old Man and the CPI.” (My own post coming soon…)

==> Tom Woods interviews Carlos Morales, a former Child Protective Services (CPS) worker. This is really good stuff for filling in a big hole in libertarian theory. There are people who are fine even with privatized courts and tanks but wonder, “What do we do about abusive parents in a free society?” This interview doesn’t provide the whole answer, but it shows that, “Just have the State fix it” doesn’t work here either.

==> I can’t remember if I already linked this, but Bob Higgs singled out Dan Sanchez’s essay on the State and war in his talk at the Mises Institute.

Krugman Then Vs. Now, Bask

This guy Dave Smith at EconLog posted the following citation:

==> Krugman, Paul (1994), ‘Past and Prospective Causes of High Unemployment’, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, Fourth Quarter, 23-43.

That looks like it could be the gift that keeps on giving. However, when I tried to get it, I could only find the article summary online. I tried emailing the KC Fed but haven’t heard back. Can any of you sleuths find it? The website made it look like you could download the whole issue, but I couldn’t get it to work.

War Doesn’t Solve the Socialist Calculation Problem

My latest at FEE. An excerpt:

The logic of voluntary market arrangements holds in the case of conscription as well. Suppose a foreign nation has amassed millions of soldiers on the border, and is preparing to invade. Wouldn’t even a classical-liberal government have to hold its nose and impose a draft on its citizens, just to deal with this emergency?

The answer is no. To see why, change the example: If a foreign nation drafted millions of its people into working on collectivized farms, would the United States need to do the same, if it wanted to grow more food? Of course not. The way to maximize food production (especially if we care about quality) would be to get the federal government out of agriculture as much as possible.

A similar pattern holds in military struggles. A free society could easily defend itself from, say, two million poorly equipped conscripts with little training, by using only, let’s say, 100,000 elite, volunteer troops supplied with advanced weaponry and vehicles from 400,000 civilians working in factories cranking out helicopters, body armor, tanks, and artillery. Foreign dictators’ reliance on a large labor-to-capital ratio for their military hardly means that is an efficient practice for a freer nation to emulate.

Potpourri

==> Alex Tabarrok relays some surprising facts about apartment hunting in Stockholm.

==> Tabarrok twin spin: Here he reviews a book on more effective altruism.

==> Overstock.com CEO Patrick Byrne was the “mystery guest” (via Skype) at Mises University this year. He pointed us to this Politico article, saying this reporter was the first mainstream one to fully grasp just how revolutionary blockchain technology will be. It goes way beyond Bitcoin. (Incidentally, if you’re new here, remember that I wrote a guide to Bitcoin with Silas Barta.)

==> Tom Woods interviews Gene Epstein on how he came to libertarianism.

==> Bryan Caplan 1, John Podhoretz 0.

==> I’m glad David R. Henderson caught the non sequitur in Krugman’s analysis of Greece. Specifically, Krugman argued that the current crisis is the fault of the rigid euro system, not the Greek government’s profligacy and overregulation, because after all the Greeks had high debt and stifling regulations 10 years ago. As David points out, uh, Krugman, they were also in the same euro system 10 years ago.

Let me pivot though and focus on something that doesn’t make sense to me. People have (rightly) ridiculed Krugman for this statement, quoted in David’s post:

ZAKARIA: Ken Rogoff on last week’s show actually said that you bared [sic] some responsibility here, because you advocated that the Prime Minister of Greece voted no, supported the no proposition, the referendum he took, in a sense defying the European creditors. The result of that was that he got worse terms. Do you think that’s fair?

KRUGMAN: Well, it’s certainly true that – I assumed – it didn’t even occur to me that they would be prepared to make a stand without having done any contingency planning.

So as I said, people have been making fun of Krugman for his overconfidence in the Greek government.

But here’s what I don’t get: Suppose Krugman’s assumption had been right, and the Greek government DID have a contingency plan, when they took his advice to stand firm (originally) against the troika. Well, even so, wouldn’t Krugman have had to know what that contingency plan was in order to say whether it was a good idea to reject the original bailout terms?

I mean, suppose Krugman’s brother-in-law calls him up and says, “Hey, I just got this job offer that pays $40,000, should I take it?” And then Krugman says, “Heck no, ask them for at least $50k.” Then the guy says, “OK I took your advice, and now I’m unemployed. Can I crash on your couch?” Krugman comes back and says, “Oh wow, when I told you to reject that initial offer and ask for more money, it didn’t even occur to me that you didn’t have another company waiting in the wings to hire you.”

Does that make any sense? Wouldn’t Krugman have to know not only that his brother-in-law had another offer, but also know what it was in order to sensibly advise him on whether to take the pending offer of $40k? For example, suppose the brother-in-law’s backup plan was a job paying $12,000. In that case, gambling with the $40k is pretty risky.

You think I’ve made my cutesy point, but I’m just getting warmed up here. Let’s start over. Krugman is acting like he’s got a pretty good handle on the Greek situation; he is quite confident in telling its officials what to do, and he’s quite certain he knows what caused the trouble, and what lessons the rest of the world should take from the whole episode. In that context, then, why can’t Krugman offer a Plan B to Greek officials, when they followed his advice and it blew up in their faces?

In summary, Krugman is saying something like: “I know so little about the actual Greek economy and fiscal situation that not only can’t I offer them a recommendation of what to do right now, but two weeks ago I was so ignorant that I assumed they had hidden information that would have rendered my advice useful to them.”

Am I being too harsh on the poor guy? I don’t think so. I think (as usual) his confident prognostications blew up in his face, and (as usual) he explains that it wasn’t his fault. It’s always somebody else’s fault.

Sequester Fun, and Murphy on Liberty Classroom

My latest post at Mises CA shows that Krugman can’t get away with saying Keynesians just needed to be more careful back in 2013, and that had they checked the numbers they would’ve known the sequester was no big whoop. Au contraire, I dug up Jared Bernstein going nuts because right-wingers were ignoring “the arithmetic” (his term).

Tonight from 9pm – 10pm Eastern I will be doing a live Q&A for Tom Woods’ “Liberty Classroom,” where I’ll be teaching courses on the History of Economic Thought in the fall.

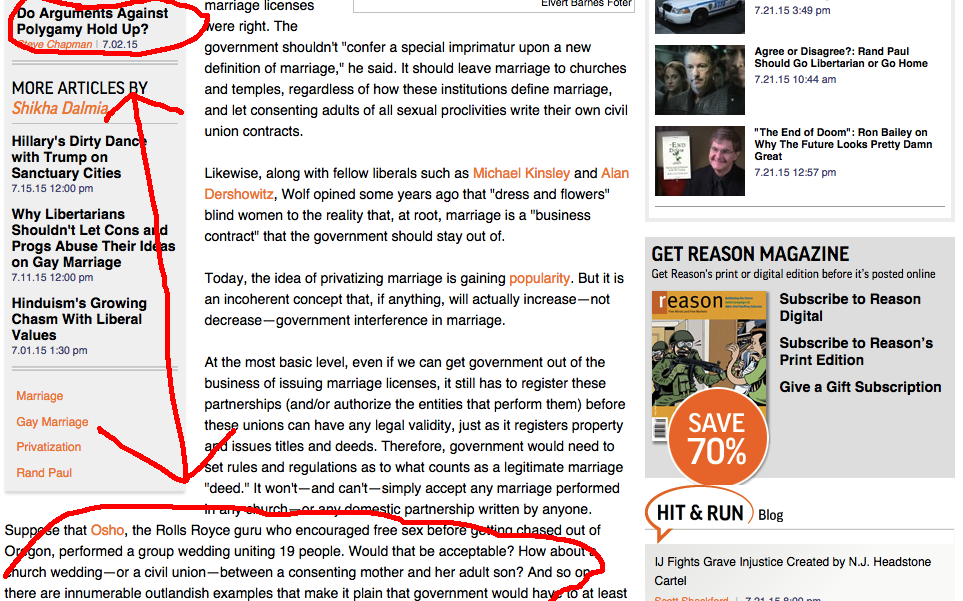

More On SSM From *Reason*

[UPDATE #2: Someone in the comments thought I was being too harsh on Dalmia, that she wasn’t necessarily contradicting her own past views on the subject. Yes, she was. See my update at the bottom of the post.]

[UPDATE: The Tenth Amendment Center was similarly nonplussed by Dalmia’s article.]

I was minding my own business, reading Ed Stringham’s article on SF private police, when I saw a “Featured Article” from Shikha Dalmia titled, “Privatizing Marriage Is a Terrible Idea.” Naturally I clicked on it, because I had been reading scoldings from some of the cool kids on Facebook that those of us who had been skeptical of the Supreme Court ruling didn’t realize that this would finally get everybody to see the wisdom of separating marriage and State.

Anyway, Dalmia not only says privatizing marriage is a terrible idea, she says it’s “incoherent.” Then there’s this:

At the most basic level, even if we can get government out of the business of issuing marriage licenses, it still has to register these partnerships (and/or authorize the entities that perform them) before these unions can have any legal validity, just as it registers property and issues titles and deeds. Therefore, government would need to set rules and regulations as to what counts as a legitimate marriage “deed.” It won’t—and can’t—simply accept any marriage performed in any church—or any domestic partnership written by anyone. Suppose that Osho, the Rolls Royce guru who encouraged free sex before getting chased out of Oregon, performed a group wedding uniting 19 people. Would that be acceptable? How about a church wedding—or a civil union—between a consenting mother and her adult son? And so on—there are innumerable outlandish examples that make it plain that government would have to at least set the outside parameters of marriage, even if it wasn’t directly sanctioning them. [Bold added.]

It would be difficult to come up with better ammunition for Gene Callahan’s running critique of libertarianism. At least in Dalmia’s case, we see that her support for gay marriage has nothing whatsoever to do with freedom, individual expression, and tolerance. No, she thinks it’s fine for a man to marry a man or a woman to marry a woman, and that’s why she wants the State to issue marriage licenses in those cases. But if three people consent to marriage? Nope, #LoveLoses because that’s just icky.

Here is what you need to do if right now you find yourself holding an outlier view, according to Dalmia:

Privatizing marriage can’t sidestep the broader questions about who should get married to whom and under what circumstances. In a liberal democracy, those who want to expand the scope of marriage have no choice but to fight—and win—the culture wars by slowly changing hearts and minds, just as they did with gay marriage. There are no cleaner shortcuts.

And there you have it. You want the right to do something? Reason‘s featured correspondent on this issue tells you: Convince 51% of us that it’s not weird.

In closing, let me acknowledge that of course there are different perspectives on this topic, and many other self-described libertarians are doing a better job of living up to their official value system. To showcase the irony, I grabbed this screenshot:

In case it’s not clear, Chapman doesn’t think the arguments against polygamy hold up.

UPDATE #2: To better understand why I’m making such a big deal out of this, and why Dalmia is contradicting her own stance on the issue, remember her opening sentence from a previous article on the Supreme Court ruling: “By advocating for limited government that stays out of the bedroom, we libertarians have played a crucial role in the American victory for same-sex marriage.”

So now we see that she was bluffing here, cloaking her personal tastes in a broad cloak of high-sounding principles that she doesn’t endorse. She very much wants the government in your bedroom, to limit occupants to two people at a time. Furthermore, they must be adults and unrelated biologically.

To be clear, I am not endorsing polygamy, incest, etc. What I’m saying is that some of the self-described libertarians running victory laps after the Supreme Court ruling are enunciating explanations that don’t make any sense.

“How Do You Reconcile Your Christianity and Libertarianism?”

Such was the question a guy asked me at Mises University (where I spent last week). To be clear, he was also a Christian and (presumably) attracted by libertarianism, but had doubts about how the two fit together.

I realize why atheist libertarians, who argue on Facebook with statist Christians, would walk away thinking that the two frameworks are incompatible. But for me, they are so naturally complementary that it’s hard for me to understand where the confusion comes in. I think the main thing going on is that (in my humble opinion, of course) many loud Christians are being inconsistent with their stated core doctrines, and many loud libertarians are doing the same.

==> If you take the Sermon the Mount literally, it is quite difficult to see how you could support a violent State institution.

==> Yes, Romans 13 admittedly sounds like it is incompatible with Rothbardian libertarianism. But then again, it sounds like it is incompatible with denouncing Hitler, Stalin, or Saddam Hussein. So you could just as easily walk up to any evangelical Republican and ask, “How do you reconcile your political views with Romans 13?” (I’ve given better answers on this thorny question here and here.)

==> The Christian ultimately cares about people’s souls, not their worldly status. I think that’s why Paul did the “shocking” thing of telling slaves to obey their masters, and telling masters to treat their slaves kindly, as opposed to trying to abolish slavery with his pen. His point was to bring the freedom of the gospel to everyone, in all stations in life. Paul himself was filled with joy as he sat in chains.

==> There is a distinction between sin and crime, even in the Old Testament.

==> There was a period when the Israelites were ruled by judges who thought they were leading on their understanding of the Law given by God to Moses, with no political authority above them. Samuel the prophet famously warned what would happen when the fickle Israelites asked for a king to rule over them (and thus ended the period of judges). To be sure, this system wasn’t something out of a David Friedman essay, but it was quite far from a bicameral legislature and a two-party system running a constitutional (sic) republic (sic).

==> Even “extreme” libertarianism recognizes the importance of law enforcement, though I predict that in modern society it would become very peaceful, very quickly. The Bible certainly teaches Christians to aid the poor, orphans, and widows. Most evangelical Christians understand that this does not automatically mean that the State should run all of these initiatives. So, by the same token, if the Bible teaches people to respect property rights, and even (though here I think it gets trickier) says that civil authorities must wield “the sword” to punish criminals, it doesn’t follow that the State should run this initiative. If the Christian objects, “But of course the State has to do it–that’s the only possible way it can happen!” then we are simply having a secular argument about the private provision of judicial and police services. The fact that my critic and I are both Christians has nothing to do with it.

==> Last thing: I’ve said it before but it bears repeating: If I’m at FreedomFest (say) and somebody asks me if I’m an anarchist, I’ll say yes because I know what the person means–he wants to know if I’m a minarchist like Ayn Rand and Mises, or if I believe in full privatization of all useful State functions, like Rothbard.

However, I actually don’t think of myself as an anarchist. Indeed, I am arguably a monarchist, because I serve a King who is master of my life. Do you know Him?

Recent Comments