Eugen Was Not PC

For the History of Economic Thought lecture on Bohm-Bawerk, I came across this passage that I remember reading in grad school:

“How many an Indian tribe, with careless greed, has sold the land of its fathers, the source of its maintenance, to the pale faces for a couple of casks of “firewater”!”

(I have no idea whether this is what it was in the original, or if the translator had some fun with it.)

Do you value justice higher than mercy?

I took the Briggs-Meyer test (due to peer pressure). (I am not telling you my score because that’s what the narcissists do.)

The question in the subject is one that struck me as very interesting. (I think they should’ve said “more highly” than “higher”?)

I thought for a bit and then decided that no, I don’t value it more. That is not say that I think it’s okay to compromise on justice. But they are certainly different values–justice and mercy–and the question asked is one more important.

As a Christian, I now answer that no, but I bet I would’ve said yes back when I was an atheist. And, now as a Christian and being aware of this difference, I am going to say I was too unmerciful back then. It’s not that I am now in favor of injustice. No, the reason I changed is that I elevated the importance of mercy since becoming a Christian.

As always, Jesus provides the role model. His actions as portrayed in the gospel accounts were a brilliant display of superhuman justice and superhuman mercy. All of the characters in the gospel accounts ring true, except His: Jesus is an unbelievable character, not because of multiplying loaves and fishes, but because, “No man could have that depth of moral strength and compassion.”

Why the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) Is a Dubious Tool for Policymakers

I don’t think I blogged this when it ran… my latest at IER.

LMS: Are the Markets Signaling Confidence or Fear?

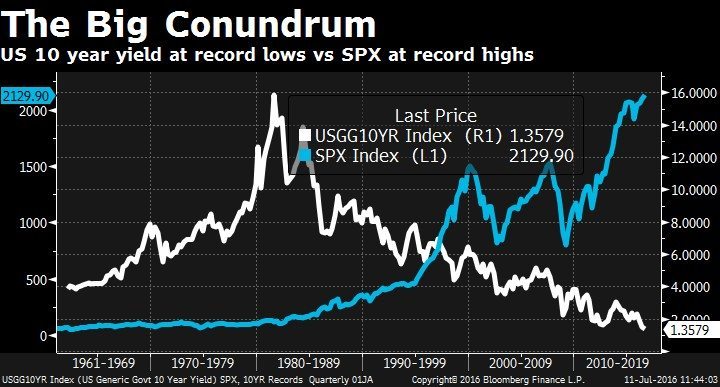

In the latest episode of the Lara-Murphy Show, Carlos and I discuss the divergence in bond yields and stock prices, which has some Bloomberg analysts puzzled. Below is the chart that motivated the discussion.

Is Bitcoin a Fiat Currency? FEE vs FEE

I have no problem with a lot of the specifics in this post by Demelza Hays (who’s my friend), but she is aghast that economists might classify Bitcoin as a fiat currency.

Well, that’s how I classified it (in my guide to Bitcoin co-authored with Silas Barta), and I think it’s consistent with Misesian monetary theory, as I explained in this earlier FEE post.

I don’t this is mere pedantic quibbling over definitions. I think many libertarians give the State too much credit when they say that it causes the dollar to be money “at gunpoint” or some such language. Here is me, discussing a quote from Mises:

Finally, we should guard against a mistake that is all too common in libertarian discussions of money. The term “fiat money” sometimes leads critics to declare that the State can turn something into money “by fiat.” At first glance, this assertion seems to follow naturally enough from Mises’s definition of fiat money. But accompanying his definition in The Theory of Money and Credit, Mises also wrote:

“In order to avoid every possible misunderstanding, let it be expressly stated that all that the law can do is to regulate the issue of the coins and that it is beyond the power of the State to ensure in addition that they actually shall become money, that is, that they actually shall be employed as a common medium of exchange. All that the State can do by means of its official stamp is to single out certain pieces of metal or paper from all the other things of the same kind so that they can be subjected to a process of valuation independent of that of the rest….These commodities can never become money just because the State commands it; money can be created only by the usage of those who take part in commercial transactions.” –Ludwig von Mises

To illustrate Mises’s point we can use the modern case of the US dollar. The US government can announce rules telling Americans which pieces of paper are and are not authentic US dollars. For example, there are rules (that the tellers at banks know very well) governing how much of a paper dollar can be ripped off, and periodically the dollars are redesigned to stay ahead of counterfeiters.

Even though the US government can tell Americans which pieces of paper are dollars, it cannot tell Americans that dollars are the money that they will use economically. The existence of legal-tender laws and other regulations complicates the issue, but nonetheless it is possible that next Tuesday, nobody will want to hold US dollars anymore and so their purchasing power will collapse, with prices quoted in US dollars skyrocketing upward without limit. This has happened with various fiat currencies throughout history, and these episodes did not occur because the State in question repealed a regulation that had previously ensured its currency would be the money of the region. Instead, the people using that currency simply abandoned it in spite of the government’s desires, resorting either to barter or adopting an alternative money.

Open Borders and NGDP Targeting: A Numerical Example

In my last post, in which I argued that Open Borders plus NGDP (or even total labor compensation) targeting would lead to disaster, I fired off some quick numbers that (although technically not wrong) made it look as if I were missing the basic logic of Sumner’s framework. Thus, David Beckworth in the comments said:

The point of a NGDP target (or some variant of it) is to stabilize the nominal income (or nominal wage) growth and allow output prices to fluctuate inversely to supply shocks. In your scenario, there would be benign deflation of roughly 10% along side the stable stable nominal wage growth of 5%. Real wages growth of 15% would still emerge.

Your scenario is basically a large positive supply shock. Whether such a shock comes from a surge in labor or a surge in technology, the Fed would keep nominal wage growth stable–which NGDP is a rough approximation–but would be indifferent to the price level. This has ALWAYS been the implication of NGDP targeting. It allows benign deflation to emerge when there are rapid gains to the supply side of the economy.

So no, Caplan’s plan and Scott’s plan do not conflict with each other. They actually complement each other.

Again, my numbers in the last post were not clear, but in the above excerpt David is not seeing the problem. So I’ll be clearer in this version:

Originally the country has 1 million workers who each make $100,000 per year. So total labor compensation in nominal terms is $100 billion.

The central bank targets 5% growth in total nominal labor compensation. So next year, workers are going to be paid $105 billion total in wages/salaries.

Suppose that at the same time, productivity jumps 15%. In other words, the workers are producing 15% more in real goods and services. Is this a problem?

Nope. As David’s comment above said, it just means the prices of goods and services falls 10%. (Give or take, we always round in these exercises even though the math isn’t exactly right with growth rates.) So the typical worker made $100,000 in year 1 with CPI at 100, and in year 2 makes $105,000 with CPI at 90.

But now we’re going to start over, and introduce a different change. We’re back to the original scenario, where there are 1 million workers who each make $100,000 per year. The central bank is still targeting 5% growth in total labor compensation, meaning next year workers will collectively be paid $105 billion.

But in the meantime, the government throws open the borders and lets in another 150,000 workers, who are identical in productivity to the original batch. Assume there are no changes in productivity because of the addition, so that total real output goes up by 15%. Is this a problem?

Yes, it is, if you think “sticky wages” and “sticky debt contracts” are a problem. There is now $105 billion in total labor compensation to be spread among 1,150,000 workers, meaning each worker gets paid $91,304. It’s true that consumer prices will drop, which (if we had perfectly flexible prices) would just compensate, keeping real wages constant. (After all, per capita the workers are producing, and hence consuming, the same amount as before the influx of immigrants.)

But the whole point of NGDP targeting is that we don’t have perfectly flexible wages and debt contracts. The worker who signed a 30-year mortgage is going to be hurt by his nominal paycheck going from $100,000 down to $91,304, even if food prices are lower.

Moreover, if for various reasons nominal wages can’t fall to $91,304, but instead are stuck at $100,000 (or close to it), then the only way to enforce the central bank’s cap on total labor compensation growth is to reduce employment. After the immigrants come in and boost the labor force to 1,150,000, if wages stay fixed at $100,000 and total labor compensation is capped at $105 billion, then only 1,050,000 workers can keep their jobs. Another 100,000 will be involuntarily unemployed. If the immigrants are identical to the original population, then we would expect a bunch of the original workers to be “thrown out of work by the immigrants.”

In this outcome, Steve Sailer would be running victory laps, and poor Bryan Caplan would have to say, “It’s not my fault! Blame Sumner!”

P.S. I’m writing this post pretty late so it’s possible I made an arithmetic mistake. If you guys catch anything I’ll fix it in the morning.

Clarifying a Problem with NGDP Targeting

[UPDATE below.]

I fear that even you, my loyal blog readers, may not fully appreciate just how insightful my earlier post on Scott Sumner was. So let me take the humor out of it and write plainly.

In this post on the Irish “miracle” (of apparently huge economic growth), Scott wrote:

I’ve argued that NGDP targeting is not always appropriate for small open economies, citing examples such as Australia and Kuwait. Actually, it’s probably much more appropriate for Australia than Ireland. The key is whether NGDP tracks total labor compensation fairly closely. Where it does, as in the US, then NGDP targeting is appropriate. Where it doesn’t, as in Kuwait, then you want to target total labor compensation, perhaps per capita.

Look at that part I put in bold. Scott added it as almost a throwaway line, but it underscores that there are all sorts of variants of his framework, and they could (potentially) lead to huge differences in outcomes.

For example, suppose Trump becomes president and then tells Scott he wants him to design the new Fed regime. After quickly deleting all of his anti-Trump blog posts, Scott comes up with a mechanism by which the Fed has zero discretion, and simply buys/sells futures contracts (in a subsidized market) to ensure that the market always expects total labor compensation to grow at 5% per annum, with level targeting. Originally Scott had thought about doing NGDP targeting, but since he was given free rein, he decided to play it safe and go directly for total labor compensation.

Unfortunately, in yet another completely unexpected move, Trump reads the work of Bryan Caplan and decides that the only way he can pay off the national debt in 8 years is to let in 30 millions new workers per year.

Contrary to the warnings of the nativists, it turns out Bryan Caplan is right: Although certain sectors get crushed, on average real wage rates are poised to go up for the average American worker, even if we restrict our attention to the original group (before Trump came in and opened up the floodgates).

However, nobody realizes–until it’s too late–that Bryan Caplan’s cool plan (when considered by itself), plus Scott Sumner’s cool plan (when considered by itself), lead to disaster when they’re combined–using the very same framework that Bryan and Scott employ.

In the first year, with the influx of 30 million new workers, total real labor compensation is poised to jump by (say) 15%. But the new monetary regime limits the total growth in nominal labor compensation to 5%. So that means on average, nominal wage rates need to fall by 10%. [UPDATE: These numbers could work, but it is probably misleading you by me picking 15%, 5%, and 10%. I think this tripped up David Beckworth in the comments below, and he understandably thought I was confused at Step 1. In a follow-up post I’ll pick a clearer numerical example.]

If prices and wage rates were perfectly flexible, this wouldn’t be a big deal. But Bryan Caplan thinks nominal wages are not flexible, and Scott Sumner’s entire case for NGDP targeting rests on the assumption of sticky prices (in particular, sticky nominal debts). For example, someone who just bought a house with a 30-year mortgage is going to be screwed when the new Fed regime, coupled with much more open borders, causes his nominal paycheck to drop 10%. His mortgage payments don’t drop, even though food prices fall 15%.

In conclusion, my point isn’t to warn, “We better hope we don’t get Open Borders plus NGDP targeting in the same year.” Rather, my point is that Scott Sumner’s case is actually much more nuanced than I think some of his biggest fans appreciate. Yes, Sumner himself can be quite nuanced, but I’m curious: For those of you who’ve been reading him for years, did you realize the policy would blow up with rapid population growth? Or that if the Irish economy had implemented it last year, its people would be in a depression right now (according to Scott’s world view)?

One more parting shot: If you’ve ever described Market Monetarism as a policy of “encouraging steady growth in total spending,” does it matter that NGDP is actually a subset of total spending? (GDP is spending on final goods and services, not on intermediate goods.)

Scott Adams and I ALSO Disagree About Politics

In an intriguing post, he writes (and I’m coming in halfway through his post, so click the link for full context):

To the great puzzlement of everyone in America, and around the world, Comey announced two things:

1. Hillary Clinton is 100% guilty of crimes of negligence.

2. The FBI recommends dropping the case.

From a legal standpoint, that’s absurd. And that’s how the media seems to be reacting. The folks who support Clinton are sheepishly relieved and keeping their heads down. But the anti-Clinton people think the government is totally broken and the system is rigged. That’s an enormous credibility problem.

But what was the alternative?

The alternative was the head of the FBI deciding for the people of the United States who would be their next president. A criminal indictment against Clinton probably would have cost her the election.

How credible would a future President Trump be if he won the election by the FBI’s actions instead of the vote of the public? That would be the worst case scenario even if you are a Trump supporter. The public would never accept the result as credible.

That was the choice for FBI Director Comey. He could either do his job by the letter of the law – and personally determine who would be the next president – or he could take a bullet in the chest for the good of the American public.

He took the bullet.

Thanks to Comey, the American voting public will get to decide how much they care about Clinton’s e-mail situation. And that means whoever gets elected president will have enough credibility to govern effectively.

Comey might have saved the country. He sacrificed his reputation and his career to keep the nation’s government credible.

It was the right decision.

Comey is a hero.

Actually I’d say it’s just the opposite. Americans pride themselves (foolishly, to be sure) on thinking they live under the rule of law, not of (wo)men. There is no surer way to delegitimize the US government that to have the head of the FBI say, “This person clearly broke the law and we would want anyone else to be prosecuted for this, but she’s politically powerful so the rules don’t apply to her.”

Also, in terms of ability to govern credibly, this will hang over Clinton should she win, and it will make people think less of Trump should he win.

Recent Comments