Shocker! Perhaps the Debt Burden Is Really About Future Taxes…?

Yes I’m being saucy, but Daniel in the comments just wrote this: “I am more curious right now how to take Grant’s point that what changes things is the taxes, not the debt. It only hurts future generations when you change the financing scheme.”

Everyone, let’s take a deep breath. Of course that’s what makes future generations poorer. Go read the words I put in Landsburg’s mouth in “The Economist Zone.” I had him make this point beatifully and with pizzazz, in a way that started David Brooks on the path to you-know-what.

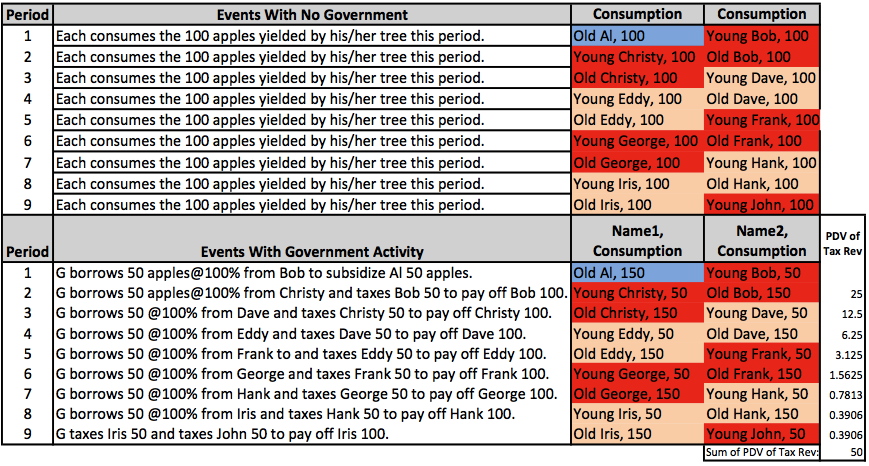

Then, recall this adapted Excel table I posted for all of you back on January 9, 2012, along with my commentary on it:

Everyone see how this one plays out? In period 1, Old Al clearly benefits. He gets a government transfer of 50 apples, paid for by a government budget deficit (there is no taxation in period 1).

Also note that I’ve put in the PDV of the tax receipts at each period. See how they sum up to 50 by the end? So one way to understand what is happening, is that the government gives Old Al a payment of 50 apples in period 1, and then spreads the tax burden to pay for it over everybody else (at some point in their lives) in periods 2 through 9. The government uses the bond market to pull all of that revenue forward in time, and give it as a spot payment to Al in period 1.

Now the crucial thing about this particular example I’ve constructed, is that Old Al is the only person who benefits from it, while every other single human being in the country, forever and ever and ever loses in this scenario. And yet, it is still the case that if we take any future time period, the “income earned by our descendants in period x is still 200 apples total.”

…

And in light of the above diagram, I would like Daniel to reconcile it with his frequently stated position: “If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”.”

Notice that Young Daniel Kuehn was annoying Young Bob Murphy even back then…

Except with this scenario.

Borrow – start a business and grow it. If the business generates more income than the debt, then average wealth goes up.

You’ve assumed that income (apples) are a constant, when they aren’t.

Apples can increase (and decrease).

The issue comes with assets < liabilities. That's the condition of all Western governments, with not a hope in hell of it reversing bar cutting the liabilities by a huge amount. That's where people lose.

Nick, the idea is to have a model that abstracts away effects like thst, so we can focus on the issue of debt, or debt vs tax. You are quite right these models don’t have much relevance for real world policies (a claim I have made myself and got attacked for). But Bob’s model isn’t designed for that.

“The issue comes with assets < liabilities. That's the condition of all Western governments, with not a hope in hell of it reversing bar cutting the liabilities by a huge amount. That's where people lose."

And where do you think this comes from?

Well right but let’s not forget the rest of my comment!

You say “of course that’s what makes future generations poorer” as if I’m coming late to the party (which I sort of am, because I was distracted by other issues), but my whole point was that Grant is saying “Of course that’s what makes future generations poorer. “ to you.

Debt is just accounting for something that could be a cost or a benefit depending on what’s being done:

– is it increasing output (no – we’ve assumed that away)

– Are we retiring, rolling over, or servicing the debt (retiring it. servicing it at the very least. not rolling it over)

These are the important questions, not the accounting practices themselves. And as Grant points out, for some reason everyone has just accepted your decision to answer all these really important questions in a way that allows you to post an extended series criticizing Krugman.

Of course that makes future generations poorer. Shouldn’t the things that affect that be the focus, rather the accounting?

That’s why I said on the blog that Samuelson wins the debate (with assists from Ryan and Grant). Because I was ultimately just arguing about (legitimate) side issues.

Another way of putting it is this:

If you have the exact same PDV cost with a transfer and taxation vs. a transfer and debt, then doesn’t that sort of suggest that the debt isn’t what matters, that’s just an accounting question.

If your position has always been “the debt isn’t what matters” that’s news to me!!!!

PDV doesn’t make sense beyond individual lives.

When we can show that all individuals past generation 5 will have lower lifetime consumption, you can pick any utility function you want, you will not succeed in refuting that each individual past generation 5 consumes fewer apples over their lifetimes.

Major_Freedom, only one “generation” (in this model) ever has to consume less (over their lifetime not in the present) and that generation can always be bondholders. (You can only make more than one generation poorer if old bondholders can convince the young to keep buying their bonds.) (No generation ever has to consume less than they can produce (in the present period) unless they buy bonds. That is: any lowered consumption would have already occurred in the past.)

The generation can either be just “old bondholders” or all “old people” depending on whether there’s a bond tax (or default), or an “old tax”.

It’s even possible for the young to pay the entire debt and still consume more (in the present and over their lifetime) than any past young generation. (Say if their productivity rises relative to the old (which with zero growth would have to fall) and the debt is small.)

Actually it’s not just one generation. It’s everyone past generation 5.

Only one generation *has* to be burdened. That’s not the same as everyone *can* be burdened. (In other words: it’s a policy choice (tax policy/decision to default) whether more than one generation gets “burdened”.) (I’m also saying it doesn’t make sense to say bondholders can really be said to be burdened since they bought bonds voluntarily and *should* assume some risk in doing so.)

And that “generation” can always be bondholders. (So not even a whole generation, only the subset of that generation that buy bonds.)

Sigh…

You still don’t get the point of this model.

The point is not to present what MUST occur, or what HAS to occur, or what SHALL occur. It is only what COULD occur.

Do you not know that this model is a counter-example yet? Come on!

The main problem with debt is if you have to pay it back. The main problem with reality is that the same resource cannot be in two places at the same time. Just because a hot Hollywood starlet is naked with her boyfriend in LA at a particular moment in time doesn’t mean that she couldn’t be with me across the continent at the exact same time.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/bob_roddis/4163003939/in/set-72157623413687847/

Your picture confuses me.

Then again, most things you say confuse me.

He’s parodying what he takes to be Krugman’s assertioon that we owe it — and pay it — to ourselves.

You should see Bob’s cartoons on momentum conservation. They’re backslappers.

Just call me Bob Foucault Roddis for my dark, ambiguous and avant-garde prose style and sense of humor.

Didn’t klnow you where a swinger Bob.

No, Foucault is a tough slog. But I usually feel like I get maybe 60% of what he’s saying, and in some texts that’s lowballing it.

You’re usually down around 30%.

The main problem with reality is that the same resource cannot be in two places at the same time.

I think this is the Keynesian idea of liquidity constraint. Desired spending doesn’t match desired investment. The people who have money aren’t the same as the people who need money.

Actually Keynes’ circular flow of income holds all spending as conceptually contemporaneous, and even Keynesians themselves often treat consumption spending the same as paying wages. My former prof for instance.

I’m talking about *desired* spending not actual spending.

“Desired” as opposed to “actual” doesn’t impact what I said.

I think liquidity constraint might have been wrong. I’m maybe getting that confused with paradox of thrift.

Anyway, my understanding is that people cut back “planned” spending at the same time. So if spending equals income, income falls for everyone.

In my head it’s that someone decides to start hoarding money so his “neighbor”‘s income falls, so his neighbor spends less and so his income falls in turn and so he spends even less and so forth. (And if people have fixed costs, contracts, debts, etc. this can wreak havoc because then prices are sticky.)

(I’m also thinking of banks who want to loan, to make money but can’t find debtors because debtors are risk averse when the economy is bad: so that’s why they cancel new “spending” projects and so forth.)

r-g is assumed as greater than zero in order to show that debt COULD burden future generations.

If public debt issue does not promote a growing economy which raises future productivity and real income, then the society must become poorer. It is not nearly as hard as the Krugman crowd make it out to be.

The increased taxes(either direct or inflation) in the future on those individuals who earn no yields from the bonds must be offsett by raising real income, or else they will be poorer relative to their parents who paid a lower marginal tax rate. Even if we assume the bondholder of the future cannot inherit the burden of past debt issue, the individuals in society who own no government paper certainly recieve no yields, and only higher taxes (perhaps some of this is offset by increased government services which leaves them mroe disposable income). But how can they possibly not be made poorer if their real income does not rise more than their taxes?

So public debt can either be good or bad. But the real question is whether society would desire for a politician(s) to be their investment advisor? If one trusts their 1) ability and 2) their motives, and 3) their incentives to make wise investments with the public’s money, then we should continue to let them borrow more and more of our investment money and spend it where they see fit. And if we think it makes our children and grandchildren better off or at worst, no worse off, then we should give the government a green light to borrow much much more money now, and let them make things much better for us now. But… I suppose this is really what Krugman IS saying.

Well right now (supposedly) real interest rates are negative so the future incomes would have to fall to not be able to service any debt incurred today. (That in addition to the whatever benefits we get from not having people unemployed long term.)

Part of the problem with the discussion is that no one (except MMT types and starve the beast Republicans) wants to to keep deficit spending at full employment.

Deficit spending does not equal nor generate full employment.

Hmm, you’re right, maybe I was assuming it as a given. But, at least in this debate the Keynesians are operating under the assumption that deficit spending, right now, will decrease unemployment

And I might add that if private investors no longer want the government paper, then the central banks in the West seem all too willing to buy it themselves. What a deal!

It’s interesting that in both economies depicted in the chart, mostly everybody ends up with 200 apples throughout their life..

But it should definitely cost a couple apples each period to employ the government bureaucracy that’s trying to redistribute the wealth.

Hence, future generations are made poorer just by the fact government exists. I like that answer much better.

🙂