We Will Not Solve the Debt Issue During This Generation

[Second UPDATE: Gene Callahan wants to be clear that he did acknowledge that he had initially misunderstood Nick Rowe’s model. Now that he gets what Rowe was describing, Gene concedes that it is possible, but points out (correctly) that we can achieve the same impact on everyone in the model through government tax-and-transfer actions, rather than using government bonds at all.]

[NOTE: I have made a few edits for typos and one misstatement–I wrote “9 generations” instead of “9 time periods” when I had Nick spell out his wager–since I first posted this. The below is just the post-correction version.]

Wow this whole debt debate has truly been a formative moment in my life. Seriously, I’m not kidding. I thought that with the crystal clear precision of a specific numerical example, all of our bickering would fall away. Don’t get me wrong: I wasn’t expecting everyone to fold up shop and say, “You win this time Murphy, but I’ll be back!” However, I expected people to say, “Whoa…You’re right Bob, this is a lot more subtle than I had initially been thinking about it. But now, using the very helpful diagrammatic framework you’ve developed, let me show you the points I have been trying to make…” (BTW, some of you have done that with me over email, and I appreciate it. I do it all for the fans.)

Fair warning: This is going to be a long post. If you are a casual reader, you may want to skip it. But I am writing this one primarily for PhD-trained economists, because even you guys (with a few possible exceptions) aren’t seeing all the moving parts on this stuff.

Now let me be clear upfront: As of this moment I am backtracking a bit, and now think that Steve Landsburg’s specific points have all been correct, except when he says that Krugman has been shedding light rather than confusion on this topic. As I will soon explain, Krugman, Dean Baker, Abba Lerner, et al. were thinking about this the wrong way–and so was I in my two book treatments of it. I think Steve has been mystified by my commentary thus far, because Steve has been thinking about these things mathematically, as opposed to using economic intuition. So Since Steve has a formal proof in his head (I’m guessing), he knows that what he’s been saying all along has been correct, and he is just trying to figure out how presumably smart guys like Nick Rowe and I can be making such boneheaded blunders.

Thus, my task in the present post is to wind back the clock, and try to remind people of what they would have thought last week before I entered the fray, and amplified the viewpoints of Don Boudreaux and Nick Rowe. To put it simply, I don’t believe any of you when you looked at my numerical example and thought it was no big whoop. No, it is a huge whoop.

Let me close this preamble with two final observations to try to convince my PhD-holding readers why you should really give me a chance to make my case:

(1) I haven’t been just dabbling on this issue while I go take a smoke break or something. (I don’t smoke, kids, and neither should you. You don’t need nicotine to be cool.) No, Nick Rowe’s original post caused me physical discomfort. I literally couldn’t get to sleep the first night I read it, because I was so sure he was wrong, and yet, there was some little voice warning me that I needed to actually write it out and prove that he was wrong. And when I started trying to do that, it hit me like a brick wall that he was right, and I had been thinking about this stuff the wrong way for at least 10 years. I have probably devoted a good 20 hours to this issue since then.

At my current level of understanding, I realize that there are at least three things tripping people up: (a) Assuming the generations don’t overlap. (b) Assuming that bonds passed on to the next generation must be bequeathed, rather than sold. (c) Assuming government tax-and-spend decisions over time have to be subgame perfect, as opposed to merely constituting a Nash equilibrium. If you have no idea what I’m talking about on each of these points, then I am pretty confident that you don’t realize how subtle this stuff is.

(2) I’m not picking on Gene Callahan, but I just want to explain why I think it’s worth all of our time to catch our breath, step back, and give Nick and me a fairer shake. Nick originally wrote his post, the one that knocked me on my keister. Gene’s initial reaction was to say that the model was “logically incoherent.” Then, I came up with an Excel spreadsheet to clarify exactly what Nick was saying in his largely verbal post. Go read his original post, in light of my spreadsheet, and you will see that I am truly just spelling out what he was describing there.

So: Gene originally said Nick’s post was logically incoherent, I spell it out with a clear numerical example, and then Gene…acts like my example just proves the points he’s been making all along. Nope, sorry, that’s a personal blog foul. It shows that this issue is extremely subtle, and people aren’t giving it the attention that I am saying it deserves. (To be clear, it’s possible Gene et al. have been making other, valid points that Nick and I are missing. But it’s hard to keep track of everything, when people keep saying stuff about our position that is simply not true. Let’s get this stuff down first, and then we can move on.)

Suppose one month ago, Nick Rowe put a riddle/challenge on his blog that went a little something like this:

I have developed a simple model of an economy spanning 9 time periods that has the following properties:

==> People live for two periods.

==> There are two people alive each period.

==> There are 9 total time periods.

==> It is a pure endowment economy with one good (“apples”) with no physical carrying of apples through time.

==> People have standard preferences: They just care about how many apples they eat, they want to smooth consumption over time, etc. There is no altruism and no envy. “No funny stuff.”

==> There is perfect certainty and everyone’s actions form a best-response to everybody else’s actions, including the government’s policies. I.e. it is a Nash equilibrium.

==> If people so choose, they can lend apples to the government, to be repaid the next period (with the revenues coming from either taxation or from borrowing again). However, these bond deals with the government are purely voluntary; a given individual will only do it, if s/he prefers the revised consumption flow to the original endowment flow.

==> There is a single act of taxation in period 9. At that time, the government will take 100 apples from someone, and give them right back to the same person.

==> Relative to the alternate timeline in which everyone consumes his/her endowment each time period, in this instance a person who is alive in time period 1 achieves higher utility while a person who is alive in time period 9 achieves lower utility. Everyone else in the model is either the same or better off, compared to the endowment baseline.

So my wager: I claim that I really am thinking of a model that satisfies all of the above criteria. If you doubt me, then you put up $500 to my $5,000. Call my bluff if you dare. After I get all takers, I will reveal whether I’m bluffing or if I actually have an example satisfying all of the above conditions. I promise, there’s no funny stuff like a person who is worse off because he finds government deficits psychologically distasteful or something goofy like that. Nope, I am either bluffing or I will present a numerical example that you will agree, fits the bill.

Now then, who would have taken Nick up on this offer? I think Gene Callahan would have, because he would have concluded that Nick is being logically incoherent; no such model could possibly exist.

Abba Lerner would have, assuming Nick Rowe is correctly characterizing Lerner’s position.

Paul Krugman would have, because Krugman thinks about this stuff by saying: “Second — and this is the point almost nobody seems to get — an over-borrowed family owes money to someone else; U.S. debt is, to a large extent, money we owe to ourselves.”

Matt Yglesias would have, because he wrote:

A few recent Krugman posts making the point that domestically held government debt doesn’t create a “burden” on the country in the sense of draining it of real resources have proven surprisingly controversial. I think the point can maybe be more clearly made in reverse. Imagine a country with a balanced budget and a large outstanding debt, all of which is held domestically. Tax revenue, in other words, exceeds spending on programs but the extra revenue is needed to pay down the existing debt. If the stock of debt is burdening the country, then it ought to be able to enrich itself by defaulting. Will that work?

Well, no. Certainly a default could set the stage for enriching specific people, since it would create budget room for a tax cut or new spending on a shiny supertrain. But the funds flowing into the pockets of taxpayers or train-builders would be coming out of the pockets of bondholders. A government borrowing money from its own citizens doesn’t gain access to any resources that wouldn’t have been available by conscripting them or raising taxes, and by the same token a country doesn’t enrich itself by refusing to make promised interest payments to its own citizens. It’s only when borrowing from or repaying foreigners that the country as a whole is gaining or losing access to real resources.

And for for sure Dean Baker would have fallen into Rowe’s trap, because Baker wrote:

As a country we cannot impose huge debt burdens on our children. It is impossible, at least if we are referring to government debt. The reason is simple: at one point we will all be dead. That means that the ownership of our debt will be passed on to our children. If we have some huge thousand trillion dollar debt that is owed to our children, then how have we imposed a burden on them? There is a distributional issue — Bill Gates’ children may own all the debt — but that is within generations, not between generations. As a group, our children’s well-being will be determined by the productivity of the economy (which Brooks complained about earlier), the state of the physical and social infrastructure and the environment.

One can make the point that much of the debt is owned by foreigners, but this is a result of our trade deficit, which is in turn caused by the over-valued dollar.

I would have fallen for Rowe’s trap too. Let me walk us all through why I would have, so we can see how our intuition–displayed clearly by Krugman and Baker above, despite Landsburg’s attempt to rehabilitate them–is wrong.

First, I would have dealt with the weird thing about the government in period 9 taking 100 apples from somebody, then handing them right back. I would think, “That’s clearly a wash. It doesn’t hurt or help a person to take apples away and give them right back. If the government took apples from the person and gave them to the other person alive in period 9, then there would be a redistribution, but Nick said that’s not what happens.”

Just to check myself, I might say, “Hey Nick! Can you give me a little more info? How does the other person in period 9 feel about the two scenarios?”

Nick would say, “Sure I’m a sport, Bob. I’ll tell you that–assuming I’m not just bluffing here–I am picturing a model where the other person in period 9 is indifferent between the two scenarios.”

Now I would be sure that I was getting $5,000 from Nick. I would reason this way: “Clearly there is nothing going on in period 9. The government doesn’t change either person’s consumption from the endowment alternative, so it is equivalent to a world where there was no taxing at all. So I’ll just move that issue to the side, and pretend there’s no taxation. Now, Nick said that was the only instance of taxation, and that any other activities are voluntary, and people will only undertake if it makes them better off. Since I’ve just proven that the government isn’t hurting anybody in period 9, and that is the only possible door through which the government in this model could hurt anybody, then clearly Nick is bluffing.”

But wait, $500 is a lot of money after all. So I would think about it some more, and come up with a completely independent argument to convince myself that Nick was bluffing. I would reason this way: “Nick claims that somebody in period 1 is better off compared to the endowment outcome, while somebody in period 9 is worse off, and the only taxing activity occurs in period 9. But he says this is a pure endowment economy, people only live two time periods, and there’s no altruism nor envy. So even if I didn’t already have my first argument, I’ve got this consideration to give me confidence: It is physically impossible for anything done in period 1, to have any connection to something in period 9. There are several generations of people who live and die in between the guy in period 1 who allegedly benefits, and the guy in period 9 who allegedly is the only one who suffers. There isn’t a time machine, for crying out loud, to suck apples out of period 9 and into the mouth of a person in period 1. So for sure, Nick has to be bluffing. I have not one, but two knockdown, bulletproof arguments.”

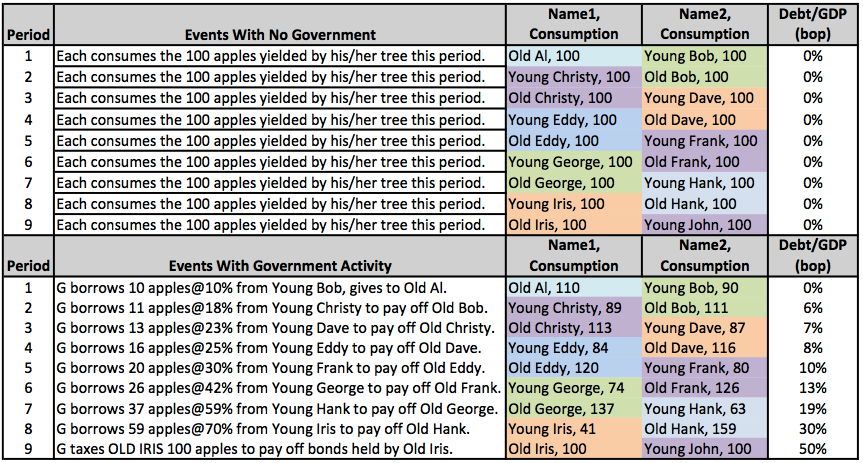

So I would have taken Nick’s wager, and he would have said, “Thanks Bob. BOOM!”:

And, after recovering from the shock/horror/joy, I would have gotten out my checkbook. And, given the quotes I presented above–and their similarity to my “knockdown, bulletproof arguments”–Nick would have collected from Gene Callahan, Abba Lerner, Paul Krugman, Dean Baker, and Matt Yglesias. He also would have collected from at least 20 people who have chimed in on all of our blog posts on this topic.

Now I’m not sure if Landsburg would have lost the bet. But I will say this: If I had read Landsburg’s blog post beforehand, it would have encouraged me to take Nick’s wager. Specifically, here are two of the points Landsburg presented in his summary post:

9. As far as future generations are impoverished by the greed of the current generation, their main beef should be not with deficit financing but with the underlying greed. Indeed, a greedy current generation is perfectly capable of impoverishing future generations without deficit spending, by depleting their inheritances.

…

13. On the other hand, even with credit constraints, deficit finance does not allow an entire generation to increase the burden on its descendants beyond what it could have done anyway (and in that sense is nothing like a time machine). It only allows some families to increase the burden on their descendants. The greatest damage one generation can inflict on the next is to consume everything in sight, and this is always possible without deficit finance.

So like I say, reading Landsburg on this issue would have encouraged me to fall into the clutches of the clever Canuck. Points (9) and (13) would have made me think, “Just so, Steve, good job clarifying all this stuff. As Nick makes clear in his alleged example, there is no altruism–so inheritances are always going to be zero, anyway–and it is a physical necessity that each time period, all the apples are consumed by somebody. So I am now even more sure, that Nick is full of it.”

(I’m not going to make this post any longer than it already is, but let me be clear that I actually think Steve’s points [9] and [13] are technically true–even in this specific case–but are highly misleading, as I hope you’ll all agree if you’ve stayed with me this long…)

Yes, it is a huge deal. It’s not merely that Krugman et al. were wrong in letter, they were also wrong in spirit. Look again at that example above: Do you not see how that is EXACTLY what the layperson has in mind, when he says, “It’s not right, us paying for government services that benefit us, by running up big deficits. If we want goodies from the government today, we should have the courage to let them raise taxes and pay for it ourselves, instead of passing the buck down to our kids and grandkids. At some point, that game has to come crashing down, and those poor saps in 100 years are going to be furious at us.”

Despite all of my “bulletproof” arguments, there is like a “wave” that flows down through the generations, from the initial “unfunded” transfer payment in period 1 to Old Al. It’s true, there’s not a time machine, but c’mon, that chart I came up with illustrates perfectly what the average Joe has in mind. In contrast, Krugman et al. have been saying stuff that is not only wrong on the specifics, but is generally misleading and would make the layperson draw the wrong conclusions. Perhaps all of their points work, if we don’t assume overlapping generations, but guess what? That means their result rests crucially on a simplifying assumption that is false, meaning they shouldn’t be trumpeting the result.

Last point to show why this is very important: A lot of you keep saying, “Deficits are functionally equivalent to taxation.” Yes, you’re right, in the sense that I could come up with a complicated scheme with no deficits (involving redistributive taxation in periods 1 through 8 ) to mimic my second scenario above.

But in the real world, it is not at all true that “deficits are equivalent to tax-financed schemes.” Yes, if the government pays old people $1 trillion today, it is “paid for” by redistributing $1 trillion away from young people today (rather than in 100 years). But it certainly makes a big difference to those young people today if they get government bonds in exchange for their present sacrifice of $1 trillion, or if they are simply hit with a tax bill for $1 trillion. The only people who have emphasized this critical point (to my knowledge) are Boudreaux and Rowe, before I came on the scene to be the Thomas Huxley to their Darwin.

I still don’t see how you are saying anything more than what Krugman initially said here:

“talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”.

This is the cost and the benefit that you’ve shown – costs and benefits on individual children, if you add up their whole lifetime income.

But within each period you don’t have a transfer of resources.

Isn’t this the Krugman position?: winners and losers but no additional burden on any particular future time period?

That’s exactly what your model shows, and what Steve, Gene and I have been trying to point out. Gene was exactly right to point out that your model shows what we’ve been saying all along.

If you look at future income levels, that remains unchanged.

If you look at individuals in the future, obviously some of them win and some of them lose – but that’s what Krugman said, from the very beginning, was “a different kettle of fish”. That’s why I’ve been saying from the very beginning that Nick Rowe (and now you) are saying what Krugman said.

I do agree Dean Baker stated the case too strongly, and that’s confused things I think. But you are making the exact same point here that Krugman did.

I should clarify – “future national income levels”, which of course is what we mean by “income” when we’re talking about the macroeconomics of deficit finance.

Daniel,

Shouldn’t be the real question of what is the layperson really saying? Is he really saying that the aggregate of all people living at one point in the future within a country will be burdened by domestically held government debt or only some (e.g. mostly the younger generation)?

As far as I would know they are saying the latter, and that it will be a fight of who will repay how much of the debt in the future, because someone (not everyone) has to pay it. Unfortunately I could not find a carefully defined example of a laypersons opinion with Google. Maybe this is because there is none. Maybe this way either side can use the layperson as he likes.

Buchanan seems to agree with my interpretation else he would not use it:

“It has been shown in this chapter that the primary real burden of a public debt does rest largely with future generations, and that the creation of debt does involve the shifting of the burden to individuals living in time periods subsequent to that of debt issue. This conclusion is diametrically opposed to the fundamental principle of the new orthodoxy which states that such a shifting or location of the primary real burden is impossible. We have examined the reasons for the widespread acceptance of the nonshiftability argument. We have isolated at least some of the roots of the fallacy. Among these are the pain-cost doctrine and the use of national rather than individual balance sheets.” Buchanan (Public Principles of Public Debt: A Defense and Restatement)

Buchanan who is with the layman is speaking of “the shifting of the burden to individuals” not the whole aggregate of people living at that point in time, and rejects specifically a national balance sheet approach. So it is really a redistributional issue although Krugman claims this was “a different kettle of fish” but does not see that this is what the layman fears.

But my opinion is just the opinion of a layman which was not the issue here, right?

DK wrote:

I still don’t see how you are saying anything more than what Krugman initially said here:

“talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”.

Daniel, in my model, what we “leave behind to our kids” in period 9 is a promise that Iris will pay Iris 100 apples. So from Krugman’s logic, we would conclude, “Iris must not be affected by today’s deficits.” And yet, she is the one person who loses.

I am astonished that you still can’t see this. There is NO redistributive taxation in my example.

Bob – in your example “our children” in period 9 is Iris and John.

Their income together without the debt is 200.

Does debt change their income?

No. In this case it doesn’t change their individual income either.

Take period 8, though. “our children” in period 8 means Iris and Hank. Their total income is 200 too. Their total income was 200 in your first example too. So Krugman again is right. Now here we observe that there is a burden being borne by Iris and a benefit to Hank. But as Krugman said, this does happen but that’s a different kettle of fish.

Debt does not impoverish generations. It may impoverish individuals.

This was Krugman’s point all along.

If you and Nick agree with that, great. That’s why from the beginning I’ve said I don’t see why Nick thinks he’s offering an alternative to Krugman.

No DK, you’re STILL not getting Bob’s point.

People are impoverished WITHOUT a corresponding “boon” to others.

Iris has less, but nobody else has more.

In order for the redistribution story to work, if someone has less, then others must have more, and vice versa.

But Bob has shown that Iris gained at the expense of herself, which means there is no redistribution of apples across a whole generation of people. It’s a straight up LOSS to some individuals. Period.

Krugman is wrong. He is saying “we owe it to ourselves” as if there is redistribution.

If you lend, but then you get the money back by financing it yourself, that’s a LOSS of what you originally lent.

You keep focusing on the triviality that 200 apples in total is consumed, when you’re not taking into consideration that these examples are taking place over time.

re: “Iris has less, but nobody else has more.”

This is completely wrong. Everybody else has more except for Iris, I believe. And then John has the same. Check it.

Or if you don’t want to check it, I have a chart on my blog.

re: “You keep focusing on the triviality that 200 apples in total is consumed, when you’re not taking into consideration that these examples are taking place over time.”

Why do you consider a GDP that does not decrease in the face of mounting debt a “triviality”. That seems to me like a VERY important point that Nick, Bob, and Paul agree on.

“Iris has less, but nobody else has more.”

This is completely wrong. Everybody else has more except for Iris, I believe. And then John has the same. Check it.

[Facepalm]

No, DK, in period 9, the time period where the government taxes Iris, the time period that Murphy wants to show that the “collective” loses on account of the government taxing to pay back debt, everybody else is most certainly NOT have more on account of the government taxing Iris.

Hank doesn’t have more because the government taxed Iris. He has more because Iris voluntarily loaned to the government expecting she was going to end up with more in the next period.

In period 9, there are losers, but no gainers. If there are losers but no gainers then there is a collective loss.

“Why do you consider a GDP that does not decrease in the face of mounting debt a “triviality”.”

Egads man, where did I say that? I never said THAT was a triviality, I said that you focusing only on the 200 total apples consumed per period is the triviality.

One more thing:

Krugman is like Old Hank in Bob’s example. Old Hank consumes 159 apples, which is financed by young Iris’ loan to the government, and Old Hank thinks “Don’t worry about all this government borrowing and spending guys, because in the future, Iris and John will not have a collective loss. There will only be distribution of gains and losses between them.”

The fact that you are pointing to Hank gaining, and Iris losing, is ironically EXACTLY the argument that Rowe and Murphy are making.

Old Hank gains because of government borrowing and spending. Young Iris gains BY THE EXPECTATION in period 8 that she is going to gain in period 9. So at that point, there is no collective loss, only collective gains.

Murphy says “Careful people, because the government borrowing is going to fall on the future generations’ (Iris’) shoulders.”

Krugman says “Let Iris and John figure it out. If one loses, the other must gain.”

See it now?

MF I think what is tripping Daniel up is that he is confusing generations and periods.

Each period has the same income, this is simply the result of Bob’s assumption and accounting.

Daniel however seems to be referring to this result when he claims that there is no burden on children and just between children.

Those children however are different generations so there is in fact a burden on future generations.

Exactly. But I think the confusions go deeper. It seems like DK’s reasons keep changing. If one reason won’t do, another is waiting in the wings.

Kavram had a great succinct explanation on this thread. It’s simple. The debt payback has to be financed. If the government defaults, the bondholders lose. If they tax to pay it back, the taxpayers lose. If the bondholders and taxpayers are the same people, then they lose what they originally lent, because they only get back what they are first taxed at that time. It would be like they owned a debt claim, and the government settled it by moving the people’s money from their right hand to their left hand and then said “The obligations are settled and we’re now done.”

“If you look at future income levels, that remains unchanged.

THAT right there is your error.

You are essentially this:

If two people consume 200 apples in one period, but expect to consume a collective 210 apples in the next period because one of them lent 100 apples to entity G at 10%, then according to you, even if G taxes one of them 110 apples, and then pays them back 110 apples, which leaves the same 200 total apples being consumed, you believe there is no collective loss. But clearly there is a collective loss because one person is worse off while the other is no better off.

The “collective” loss is due to some people losing, WHILE NOBODY ELSE GAINS WHAT IS LOST.

Al gains. Bob gains. Christy gains. Dave gains. Eddy gains. Frank gains. George gains. Hank gains.

Iris loses.

John is window dressing.

Please don’t tell me “nobody else gains” if you’re not willing to take the time to add two integers together.

DK, when the statement “nobody gains” is made, the context is PERIOD 9 only, which is the “future generation” that Rowe and Murphy are saying will lose on net, collectively if you will.

Krugman is saying that there will be no future collective loss because he incorrectly believes that if there are losers in the future, i.e. Period 9, then there somehow must be GAINERS who gain because the losers lost.

He is probably thinking that as long as Americans own the debt, then there allegedly cannot be a collective loss.

Now you are admitting that in period 9, there are only losers, and zero gainers at the expense of the losers.

That is an admission Murphy and Rowe proved Krugman wrong.

Don’t worry about admitting Krugman is wrong. It’s not like him being right is the reason he’s so popular.

Daniel,

But within each period you don’t have a transfer of resources.

This is not right, as Bob’s example shows. Within periods, resources are redistributed. Between period, no resources are redistributed. That would involve consumption goods travelling through time.

I mean – what do you think Krugman was saying?

That income in a future period would be the same AND that each individual person’s income would be the same?

He seems quite clearly NOT to be saying this. He explicitly said on several ocassions that certain individuals would be hurt by it and certain individuals would benefit. He gave several examples too.

DK, you’re still not seeing what Bob is showing.

You say:

“He explicitly said on several ocassions that certain individuals would be hurt by it and certain individuals would benefit.”

Bob has shown that NOBODY ELSE IS BENEFITING. The government taxing Iris to pay back Iris is NOT a “benefit” to John!

You’re just looking at the trivial fact that John consumes 100 apples and you fallaciously believe that what Iris lost must have gone to John’s gain, because you still see 200 total apples being consumed.

I’m with Bob. It is BAFFLING, ASTONISHING, that you cannot see this. Bob is pulling teeth out of a tyrannosaurus, and you think he’s playing with an Iguana.

re: “Bob has shown that NOBODY ELSE IS BENEFITING. The government taxing Iris to pay back Iris is NOT a “benefit” to John!”

Right – in Bob’s example Iris benefits and Iris bears a cost, so it’s a wash with Iris and it’s a wash with the national economy in period 9.

Iris as an individual – throughout her life – bears a cost.

What’s the problem here? What do you think I’m missing? Did I ever say John enjoyed a benefit? Why are you so triumphant about that? Who cares?

re: “You’re just looking at the trivial fact that John consumes 100 apples and you fallaciously believe that what Iris lost must have gone to John’s gain, because you still see 200 total apples being consumed.”

When you find where I said this, you let me know MF.

“Right – in Bob’s example Iris benefits and Iris bears a cost, so it’s a wash with Iris and it’s a wash with the national economy in period 9.”

Then you agree that Krugman is wrong to say that we should not worry, because “we owe it to ourselves.”

“Did I ever say John enjoyed a benefit?”

YES! You favorably quoted Krugman saying:

“He [Krugman] explicitly said on several ocassions that certain individuals would be hurt by it and certain individuals would benefit.”

You are implying here that if there is a loss to some individuals, that it must be the case that others are benefited, to balance things out, to “explain” why there remains 200 total apples consumed per period.

Bob showed that nobody else is better off to “balance out” the fact that some people are worse off, that can enable Krugman to say it’s all a redistribution story.

“Why are you so triumphant about that? Who cares?”

Trust me, triumphant is not what I am feeling right now.

Who cares? What kind of a question is that? You’ve been hip deep in this since the start, and NOW you’re saying who cares?

You’re like someone who just trained for a year to run a marathon, and then the race starts, you thought you were in the lead, then you fell just before the finish line, then after Murphy passed you, you say “Bah! Who cares? It’s just some stupid race.”

To reiterate, as Murphy tirelessly pointed out, the losses experienced due to the taxation to settle the debt does NOT generate a corresponding gain to anyone.

You mistakenly believe that as long as 200 total apples are consumed each period, that it can ONLY be a redistribution story.

Major Freedom – please read my comments so this doesn’t have to drag on.

I did say a person benefits and a person bears a cost in period 9, so that the total income is 200. I said the person that earns a benefit is Iris. I said the person that bears a cost is Iris.

You are confusing gross and net benefits.

I don’t think I said anywhere that John benefits from any of this.

DK, I AM reading your comments. You just think that the problem must be in my comments because we disagree.

No, there is nobody that gained what others have lost IN PERIOD 9. You are incorrectly presuming that there has to be offsetting gains to the losses. There isn’t. Yes, it’s true that John consumed 100 apples, but that “gain” is due to his own production, and NOT because he gained at the expense of Iris who lost.

The loss of Iris did not get redistributed to others in her “generation”, period 9. But that is what needs to be the case IF Krugman is going to be right.

Nobody is confusing gross and net benefits.

You didn’t say it explicitly, but your defense of Krugman’s quote regarding losses and gains above, REQUIRES you to accept that if there are losses in period 9, then somehow there must be others in period 9 who gain what was lost in that same period 9.

That is what the whole “we owe it to ourselves” argument requires.

That Rowe and Murphy have shown that an entire generation loses on net, i.e. Period 9, it means that it is NOT a redistribution story a la Krugman.

How does Iris benefit? She lends 59 because she expects to consume 100 in the next period. This does not occur because Iris gets taxed.

Each individual consumes > 200 and the economy produces 200. The way this is done is by financing the consumption in excess of 200 through deficits. The sole person who does not consume > 200 – not even close – is Iris. So who bears the burden of the deficits in all periods previous to Iris if not Iris? This consumption that is in excess of 200 has to come from somewhere.

This:

“talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”.

Is therefore simply not true.

Martin, it’s more accurate to say that Iris lends 59 apples hoping to get 100 apples back, which will allow her to consume a total of 200 apples (100 from the pay back loan, and 100 from her current production) in period 9.

By saying she lends 59 in order to consume 100 later on, you are misleading those who think Krugman is right into thinking AHA! Total consumption remained 200 (instead of 300 that was expected on account of Iris’ lending to G)

Part true, but then they’d have to implicitly assume that 100 was created ex nihilo.

You’d expect that (mainstream) economists would have learned not to violate the laws of thermodynamics by now 😛

I’m not sure who that is aimed at, but I’ll just say that the assumption in the example is that 100 apples will be produced by each person per period.

In period 9, Iris expected to consume 200 apples (100 from her current production and 100 from her prior loan). She only consumed 100 because the government took 100 apples from her to pay her back, leaving her with 100 apples.

Nothing is created ex nihilo in any of these models, Martin.

Daniel if nothing is created ex nihilo, then 9 periods of 200 income will yield a total income of 1800.

If 8 out of the 9 people consume more than 200 through deficit financing, one person has to bear the burden of that excess by consuming less than 200.

If that’s not leaving a burden I don’t know what is.

This:

“talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”.

does not make any sense whatsoever then.

re: “If that’s not leaving a burden I don’t know what is. “

It does leave individual burdens.

This has always been the claim.

Daniel, you quoted

“talking about leaving a burden to our children is especially nonsensical; what we are leaving behind is promises that some of our children will pay money to other children”.

Previous generations consumed, future generation pays. Is this or is this not a burden to our children?

DK:

It does leave individual burdens.

This has always been the claim.

That’s incredibly misleading. You’re only focusing on one part of the claim “that was always made.”

The other part of the claim “that has always been made” is that should there be any individual burdens that exist in the future, they must be accompanied by individual gainers who gain because individually burdened people are burdened, in that same future generation.

That is what the whole “we it it to ourselves” means.

re: “How does Iris benefit”

She gets 100 paid to her by the government.

Daniel,

And who pays for that benefit? Who bears the burden of that benefit?

Financed by Iris herself. That is not a gain.

I finally get it – in the last period, a burden will have to be shouldered by either bondholders or taxpayers. If the gov’t defaults, bondholders take the hit; if they pay back their obligations, taxpayers take the hit. If a bondholder is simultaneously taxed and repaid, then they lost money when they originally purchased the bond.

I feel like it shouldn’t have taken me so long to figure this out…

BINGO kavram. You succinctly explained what verbose people like me require 54 posts to say, LOL

You get it.

Bob,

Let me get this straight by rephrasing it.

Assume an individual who lives for two periods. He has an endowment of 200 on a bank-account. The first period 100 is released and the second period the other 100. Now assume that the individual gets plastered in Vegas in the first period and gambles away 200. He now has a debt in period 2 extinguishing his consumption.

Is it your point that it does not matter who he owes it to? Is Krugman’s argument equivalent to owning the bank and lending 100 to himself? Sure he gets an IOU, but he also has a debt corresponding to that IOU summing to zero, because the endowment has been consumed in period 1.

I mean I could add a second generation in the second period instead that has to live on that endowment and inherits the bank, but the conclusion would remain the same. The individual who has to consume in period 2 bears the burden of the individual in period 1 going to Vegas.

1) You have totally misinterpreted my remarks vis-a-vis you and Rowe. I have e-mailed you explaining how you did so. I expect we will see a correction here soon.

2) “Yes, if the government pays old people $1 trillion today, it is “paid for” by redistributing $1 trillion away from young people today (rather than in 100 years). But it certainly makes a big difference to those young people today if they get government bonds in exchange for their present sacrifice of $1 trillion, or if they are simply hit with a tax bill for $1 trillion.”

Well, so you are saying here that debt places less of a burden on future generations than taxes?! You have just rejected your own argument?

“Last point to show why this is very important: A lot of you keep saying, “Deficits are functionally equivalent to taxation.” Yes, you’re right, in the sense that I could come up with a complicated scheme with no deficits (involving redistributive taxation in periods 1 through 8 ) to mimic my second scenario above.”

No, Bob, what Landsburg and I have shown is that it is trivially simple to mimic your debt scheme through taxation!

You can’t mimic debt through taxation.

Taxation is a loss.

Debt is a voluntary lending with an expectation to gain later on.

Yes, you can use either debt or taxation to force 200 apples per period, but that doesn’t mean you can use taxation to mimic debt, because you’d be ignoring the expected gain through the lending that is NOT had because there is taxation to finance that gain.

By the way, I have pinpointed exactly why Bob is amazed that we don’t see his point, and it is because his point involves an invalid shifting between ex ante and ex post analysis:

http://gene-callahan.blogspot.com/2012/01/how-murphy-is-achieving-his-result.html

These models are all just measuring total apples consumed and no-one has any clue how the actors feel about the whole thing.

Its clear that measured thus the earlier generations do better than the later generations in these models. You’re objection seems to hinge on how the bond holders evaluate their loss of consumption in the first period and increased consumption in the last period.

I am wondering if this matters. At least for me the interesting thing is how one group of tax payers can increase their consumption at the expense of a later one. As long as the govt can find bond-holders to carry the debt through time this has been shown to be possible. Why is the subjective feeling of the bond-holders relevent to that ?

Why do we keep saying Old Iris gets taxed 100 apples? She’s actually getting taxed 67 apples (or whatever she was promised for her 59).

It must be recognized this taxation is just a thinly veiled default on the bond Iris is holding. Consider the scenario – Middle Aged Iris, after deferring her consumption in period 8 (Old Hank ate her 59) apples, walks down to the Department of Apples with her IOU for 67 apples. She also brings her freshly harvested 100 apples she was about to consume on her own. She goes to the desk, presents her IOU to the goon at the window.

Scenario A: The goon at the apple department laughs in her face, tears up her IOU, tells her to beat it – this is clearly a default

Scenario B: The goon points a gun at Iris and says “Give me 67 apples or I shoot you”. Iris does, the goon laughs as he gives the apples back and says “Ha, now we don’t owe you anything – now beat it!”

Clearly, Iris has no reason to prefer either scenario – they are both effective defaults. Retiring a bond by taxing the person for the face value is for all intents and purposes, a default..

The key here is that Krugman is explictly arguing “no defaults”. He assumes that production will increase, and the amount of the bond will seem trivial to later generations. Now maybe “no defaults” is a bad assumption. But because Krugman argues no defaults, and this scenario contains a de facto default (nor does it prove that defaults are inevitable), I don’t think it can be used to disprove Krugman

http://mises.org/daily/5260

Thanks Tel I had forgotten about that! And now we come full circle: My critique of MMT shows why Abba Lerner’s thoughts on deficit finance were wrong! How fitting.

I agree, but my point stands – if the burden, as described in this post, on our children is caused by default (or the taxation/redemption shuffle), it does not refute Krugman because Krugman is explicitly stating that the government will never default

I rather suspect that if you call him on it, Krugman will say:

[1] inflation is not a default.

[2] the Tabitha and Sam affair is not a default.

[3] voluntary haircuts are not a default, where Krugman and co. get to define the meaning of “voluntary”.

After that it becomes a legalistic argument over the definition of “default” but that’s a predictable waste of time if you ask me.

“Why do we keep saying Old Iris gets taxed 100 apples? She’s actually getting taxed 67 apples (or whatever she was promised for her 59).”

Whence do you get 67? (Young) Iris in time period eight lent 59 apples to the government at 70% interest, which means (Old) Iris is supposed to receive 1.7*59–or 100 (rounding down)–apples in time period nine.

The government, in order to pay her 100 apples, first taxes away her 100 apples in order to give them back to her.

“It must be recognized this taxation is just a thinly veiled default on the bond Iris is holding. ”

If it is, then there are “thinly veiled default[s]” in the U.S. whenever the government uses tax revenues to pay off debt.

By issuing the debt, the government made it look as if there was more wealth than there really was. After several generations, the interest on the debt becomes greater than GDP (a claim on more apples than exist). The government extinguishes the debt through taxation. This is not exactly a net burden on the population at the time when it happens, although it may feel like it – because that wealth never existed in the first place. It looks like a loss because trees plus government bonds get converted into just trees.

It may be worth trying to see what the difference would be if the money was taxed instead. First, the money would come from everyone, rather than just lenders. (This difference isn’t apparent in the example.) The government’s demand for loans probably pushes up the rate of interest. I think that by borrowing instead of taxing, the government favours lenders over non-lenders.

(I accidentally put this comment on the wrong post.)

“Anyone who is not shocked by quantum theory has not understood it.”

— Niels Bohr

I’ve been bashing at my spreadsheet and I’d say a more realistic long-term interest rate might be 7%, I’ve thrown away any roundoff, and I presume that the younger generation can live on half the apples that they actual produce before there is social unrest (i.e. 50 apples in the young part of the cycle). That gives a total of 22 generations from start of the scheme to the point at which is reaches it’s natural limit.

So Let’s presume 25 years per generation: 2012 AD – ( 22 * 25 ) = 1462 AD just a bit before America was discovered and around about the rise of the banking industry in Europe. Now, if you tell someone that an event in the 15th Century is finally reaching culmination with the modern debt crisis then people will regard you as less than human. Check what the numbers say… that’s exactly what they say. Freaky!

Yes I’m now in the picture that there is an unseen danger in this type of inter-generational credit system. However, I’m still inclined to draw the attention back to government spending. If a private group want to sit on a time bomb for hundreds of years, well that’s their choice and when the bomb goes off they only hurt themselves. However, government spending is the willful action that puts the time bomb under all of our seats. I don’t dispute that such a time bomb exists, but the usage thereof makes a difference.

I’m still trying to see it from both points of view (policy wise) but yes I’m genuinely shocked by the implications of this model, it is counter-intuitive, you should not be able to maintain a scam for such a long time.

Yes I fully agree, there’s a difference only in perception. The inter-generational debt system allows the outcome to be hidden and the people who finally pick up the tab never got a chance to vote in the election. If parents could be trusted to vote on behalf of their descendants 20 generations down the line then it would not be a problem. Mind you, in the modern world we don’t trust people to select their own retirement investments so go figure.

A few observations here:

1. The Murphy camp uses a different definition of the word ‘generation’ than the Krugman camp. What Krugman calls a generation is a ‘time period’ in Murphy’s terms. So when Krugman says we don’t make future generations poorer he is just saying that total consumption in each time period will not be affected. This is a linguistic divide rather than an economic one.

2. Dr. Murphy has shown that you can assume a model in which both debt and passing on of a burden to younger people coexists. He has not proven a link between both and especially has he not proven a causal relationship. The outcome for Iris could as well be caused by other assumptions that he makes e.g. the absence of any altruism or the apparent non-existence of inheritance. You cannot deduce causality from co-existence.

3. Even if you assumed a relationship between debt and the burden and even if you proved that debt is a necessary condition for this outcome (which I think you cannot) you still would not have proved that debt is a sufficient condition for it. I can easily show a counterexample in which a lot of debt exists but young people benefit: http://s1.directupload.net/images/120108/qvuiio7l.jpg . I.e. you cannot deduce the burden from the mere fact that there is debt. You need additional information.

4. There are many reasons to be opposed to debt. The statement “we owe it all to ourselves” is correct if you think in terms of collectives but misleading in that it creates the false impression that nobody will bear a burden for it. The fact that total consumption doesn’t change in each time period does not help Iris at all. She is worse off and that is what matters to her. The benefit of one person doesn’t legitimate the illegitimate burden of another person.

1. “Generation” is a bit of a loose term, so for statistical purposes and global averages it only spans one time period, but any particular generation sees the whole of their lifespan, not half (i.e. two time periods). The split perspective is what makes the illusion so effective.

2. The Abba Lerner quote is: “You can’t make real goods and services travel back in time, out of the mouths of our grandkids and into our mouths. “ and Murphy/Rowe have proven this categorically wrong. It is possible for a whole generation to get ripped off by debt (i.e. the Iris generation) if they happen to be at the point where the debt unwinds. The trigger event that caused this might have happened many generations before.

3. I agree with this in as much as if government invests the money in worthwhile infrastructure, and that infrastructure is indeed useful to future generations then the debt can be paid off by tax on usage of the infrastructure rather than direct income tax. However, real-world examples of this are rare. Murphy presumes government spending goes straight to consumption.

4. I think that once more brings us back to the Krugman adage, “Economics is not a morality play”. IMHO, Krugman needs to be constantly and unmercifully hounded for that, until he sincerely apologizes. Using inter-generational debt allows a sleight of hand to hide the immorality, but since Krugman has openly disavowed morality entirely, it make you wonder why he needs to hide anything?

Aggred in principle. I just want to add re point 2 that proving that someting is possible doesn’t prove that it is inevitable. And sometime at least I head the impression that Dr. Murphy was not only trying to prove that it is possible but also that the burden is always the logical consequence of debt. At least that’s the impression I got when I watched the interview with the judge. If he says it is possible but we need more informatin to determine whether it is happening right now in our economy, I fully agree.

Re 3. I am not so sure whether you really need infrastructure spending. In my opinion, the absence of destructive spending would be sufficient. Still, quite an unrealistic thing to expect from a govt.

Re 2.:

Dr. Murphy just posted this in the other comments section “EVERYONE ALIVE TODAY make ourselves richer, and ALL of our grandkids poorer, using deficit financing”

You see, he is not saying that it is _possible_, he is saying that it is the inevitable logical consequence;

Christopher wrote:

You see, he is not saying that it is _possible_, he is saying that it is the inevitable logical consequence;

No, you quoted me talking about a specific numerical example. I’m not saying those conditions are always the case, I’m just saying they might be. And since I took Krugman, Dean Baker, etc. to be giving “insights” about the debt that would rule out such a possibility, I was demonstrating that they weren’t helping people think about it the right way.

Maybe I should add:

2a. Dr. Murphy has shown that it is indeed possible to set up a system that works as if ressources were transferred back in time. At least from the viewpoint of an affected individual it feels as if they were sending ressources back in time. For everyone who is not only concerned with aggregate output numbers but also with the individuals involved this is an important thing to know. The question then would be whether the current state of the US economy is in fact such a system or whether it resembles more the scenario I descibed under ‘3.’ above.

The key is that _both_ Bob and Iris would have voted against the _tax_, but the borrowing scheme encourages _everyone_ at the time to choice to support the borrowing and taxing scheme.

Al doesn’t ever think about Iris — she’s too far away conceptually and by blood for Al to consider.

If all generations could weight in, and all of these saw what was taking place — the borrowing plan would be opposed.

With borrowing the politician can get a buy in from everyone in the current generation — because the ones who get hammered come later, and the knowledge / uncertainty problems makes it is insuperably impossible to know exactly who those hammered will be.

Yeh, the average guy does know what is going on — and the math constructions and conceptual constructs used by economists do the same work as a spike to the brain, or a brain stroke. They make destroy parts of the brain that make it possible for humans to perceive specific things or think specific things, e.g. like folks who can not see faces because that part of the brain has been destroyed by a stroke, etc.

Bob: OK. Now *you* have taught *me* something in this post. Something i didn’t see before.

But, you also need to clarify one thing that you said.

“There is a single act of taxation in period 9. At that time, the government will take 100 apples from someone, and give them right back to the same person.”

That is what happens in equilibrium. (And I think you are right that it is subgame-perfect, but the government is not truly a player in the game.) But that is not something that happens at all nodes of the game. It is a conclusion, not an assumption. The assumption is that the government will tax one specified person, and the give the apples back to whoever holds the bond.

I’m still thinking about this.

This is a very good post Bob.

“(c) Assuming government tax-and-spend decisions over time have to be subgame perfect, as opposed to merely constituting a Nash equilibrium.”

I understand the difference between Nash and subgame perfect. But I don’t understand what you are saying here. I thought the government was a strategic dummy in this game. You are saying something different, i think.

And, as I said in my previous comment. It is an assumption that the government will take 100 apples from some pre-specified person. It is a prediction that the government will give apples back to that same person in equilibrium.

I think.

If the government proposed to tax Bob & give the money to Al, Bob would oppose it.

The government sets up a scheme where Iris takes the hit, and neither Al nor Bob have any idea how or why tor even that his will happened (and in the actual world no certainty who will take the hit).

Krugman has told them what there is no cost to future generations “we just owe it to ourselves”.

So Iris gets screwed.

This is what the public understand — and this is the part of the brain which has been removed from economists, with their math constructs and conceptual constructs acting like a stroke making some it impossible any longer to see parts of the real world, like stroke victims with damaged brains who can no longer see faces.

Dumb question – why are the interest rates paid by the government increasing? Are we just assuming they have to pay more to borrow?

That’s my guess.

However I think that even if the interest rate stays at 10%, nothing of substance would change. It will just take more periods before the government has to borrow more than what can be produced, and thus tax someone.

its a nice model.

landsburg would say the government imposes a growing tax from young to old which it eventually cans. and he would be right.

but i guess what nick and you are saying is that deficit financing and bonds are the very name of this tax (or the mechanism by which landsburgs tax is obscured to the public) and that krugman saying don’t worry is misleading because the final generation before the blowup does get shitcanned in terms of it pays the elders and then gets shafted in return.

interesting.

“The only people who have emphasized this critical point (to my knowledge) are Boudreaux and Rowe, before I came on the scene to be the Thomas Huxley to their Darwin.”

FYI, I did leave a formal double entry accounting proof of the correctness of Nick’s model at Nick’s (4 days prior to your post here):

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/01/the-30-years-debt-burden-non-war.html?cid=6a00d83451688169e20162fef52c26970d#comment-6a00d83451688169e20162fef52c26970d

lets swap it around, old adam sacrifices 10 apples to give to young bob who eats 110 (or its a government program benefit the young or we throw you in gaol)

he has to do the same but it grows every generation until old hank is down to his 41 apples and people say enough! no pensioner can live on less than 41 apples, lets stop the whole transfer thing.

in this example the initially impoverished generation is long dead (adams apples) and iris ends up eating more but everyone else has consumed less throughout. lesson: it matters where your transfers go so be careful.

also beware of being the last person in a ponzi scheme (any scheme where you are paid more than you put in)

finally, the only real interest rate can be growth.