Future Generations Will Be Indebted to Me for the Clarity of This Exposition

OK my piece de resistance. I’m going to post this on Facebook, so let me start from scratch:

I am responding to Paul Krugman’s recent claims on why the standard political debate on the government debt is totally wrong-headed. (For a good summary of his position, see this NYT piece.) Specifically, Krugman conceded that if foreigners held U.S. government bonds in (say) 100 years, then those future American taxpayers would indeed be burdened by having to service the debt. However, Krugman said that empirically, Americans basically would “owe the debt to themselves” and so today’s deficits wouldn’t impose a burden, at least not for the simplistic reason that the average fan of Rush Limbaugh or Sean Hannity would believe.

I would have agreed with Krugman two weeks ago; indeed, in my own textbook I made similar observations. To be sure, I still thought it was irresponsible and would impoverish future generations if the government ran big deficits today, but I didn’t think it was because “hey, our grandkids will eventually have to pay this debt off, and at that time it will be painful to them.”

I was wrong. Krugman is wrong. The difference is, I realized it and–now that the scales have fallen from my eyes–I am the most zealous defender of the layperson’s view on this. The person who made me see the light was Nick Rowe in this post, but now that I understand what the issues are, I realize in hindsight that Don Boudreaux (relying on insights from James Buchanan) was right from the get-go as well. (However, I wouldn’t have seen it by just relying on Boudreaux’s general arguments. It took Rowe’s simplistic thought experiment to finally make it click in my thick skull.)

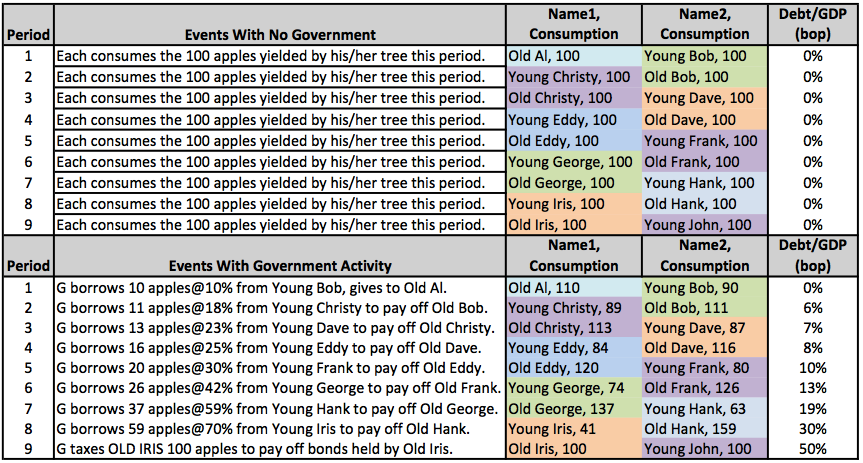

OK, so consider the following simple world: Every period, there are only two people alive, an old person and a young person. Each person lives two time periods. (I.e. the young person turns old the next period, then dies and is replaced by a new young person.) Each person owns a tree that yields 100 apples to be eaten. The apples can’t be stored for future consumption, and they are seedless so we can’t plant new apple trees. This is what economists call a “pure endowment economy with no physical saving.”

People’s preferences are intuitive. Other things equal, they want more apples in any given time period. There is no altruism nor envy. People also prefer to “smooth” consumption over time. So for example, someone would rather eat (100, 100) apples in periods (t1, t2) rather than eating (99, 101). However, someone might be prefer to eat (99, 105) rather than (100, 100) because the preference for more apples outweighs the preference for smoothing. (I’m being a bit loosey goosey here, but we could make this really rigorous if needed.)

Now consider the following two histories of this simple world:

I need to be quick, so you might need to read some of the links above for the full explanation of this chart. But let me fill in some of my assumptions: In the second example, all of the government’s deficit financing is purely voluntary. I.e. somebody who gives up apples as a young person, for a promise to eat more apples in the future, prefers that stream of consumption to his original endowment possibility of (100, 100).

So compare the outcomes for each person, in the original history versus the second history. Clearly Old Al in period 1 likes the deficit scenario better; he gains. Clearly Young John in period 9 is the same in either scenario; he isn’t affected by the deficits. Also–not as obvious but by stipulation–Bob, Christy, Dave, etc. prefer the deficit scenario to the original scenario. For example, Bob prefers (90, 111) to (100, 100).

So this is looking pretty good, huh? We’ve got a bunch of people who are better off, and one guy who is the same. Looks the government improved the free-market outcome, right?

Oops there’s one person left to consider: Iris. How do you think she feels about this arrangement? Originally she consumes (100, 100). In the deficit scenario, she consumes (41, 100). So she is clearly harmed by this.

But look how I’ve constructed this example. In period 9, the government taxes Iris 100 apples, and then hands them right back to her. So Krugman would look at that and say, “It’s a wash. Iris hasn’t been hurt by the gigantic government debt being passed down through the generations, because in period 9 Iris was unaffected by it–she owed the debt to herself. It’s a total wash.”

Now we can see precisely why that is a silly argument. Sure, if the government handed Iris a bond promising 100, then taxed her to retire the bond, it would be a wash. (We’re neglecting deadweight losses of taxation, etc.) But the government didn’t hand Iris the bond for free, instead it auctioned it off to her in period 8 for 59 apples.

Now somebody like Steve Landsburg is going to look at the chart above and say, “I don’t know why you Austrians keep picking on poor old deficit finance. It gets a bum rap. The real burden imposed on Iris is the taxation in period 9. Her ability to engage in a mutually agreeable bond deal with the government, actually makes her better off than if she were forced to consume (100, 0). So deficit finance actually helps Iris; it’s the taxation that hurts her.”

OK sure Steve, that’s technically right. But COME ON. Once the government in period 1 gives a freebie of 10 apples to Old Al, and doesn’t have the political cajones to directly tax Bob to pay for it, future generations have their fates sealed. As that government debt gets kicked down through the generations, somebody has to get screwed: either the taxpayer who retires the debt, or the bondholder left holding the bag when the government defaults. Depending on the timing, the chickens might not come home to roost until the people who must singly or jointly suffer the brunt of this pain, weren’t even alive when the original transfer happened.

The layperson is basically right, and Krugman et al. are basically wrong. Government deficits today do impose a burden on future generations, because of the “naive” fact that the debt needs to be serviced/repaid. Yes, if the government does something with today’s expenditures that might help our grandkids, then perhaps they will thank us for it. But either way, it is a complete non sequitur to say, “The national debt per se can’t hurt our grandkids, if they owe it to themselves.”

In closing, here’s an analogy of the positions:

LAYPERSON: Whoa, that nutjob went into a restaurant and killed 5 people with a gun.

KRUGMAN: You idiot, you should study physics. Energy is always conserved.

LANDSBURG: Krugman has a good take on this issue, and I would add just one caveat: Guns don’t kill people, bullets do.

I propose two more charts:

#3. Where there’s an initial transfer from Old Al to Young Bob

#4. Where there’s the same transfer from Young Bob to Old Al paid for by a tax on Young Bob

Comparing your #2 to #4 should amply demonstrate the Barro point. This really isn’t about debt.

Comparing both #2 and #4 to #3 should demonstrate that the “burden on our grandkids” blather has nothing to do with the debt either. The generational burden is entirely determined by the nature of the initial transfer. It has nothing to do with debt.

Good summary, this is easy to understand!

I propose a fifth chart. One that takes into account the Samuelson take on debt (it’s OK as long as economic growth outpaces interest rates).

Agreed.

One complication I would want to add is uncertainty about future government spending per my thoroughly ignored argument.

That is, make it so the government is running an additional tax-funded program, which people expect (hope?) to stop existing in a future, meaning they think they won’t be taxed more to pay off the bonds they hold — i.e., they think the government will terminate the spending program as a means to pay off bonds.

Why isn’t anyone discussing the impact of government debt on capital reallocation, credit expansion, and currency debasement? Is it because the quasi-monetarists will tell us that the debasement is “only nominal,” or is it because everyone is so caught up in the ethics of transfer payments that they can’t be bothered to discuss the ethics of market distortions?

Bob, you’ve done a great job of explaining transversality conditions. The reason it isn’t a convincing argument is that no one ever seems himself/herself as Iris. Iris is always some magical person in the future that no one ever has to worry about. So, because transversality conditions are never a credible threat, nobody cares or will care.

But I think people care a lot if we explain to them that the reason they don’t have a job today is because W. Bush used deficit spending to finance two simultaneous land wars. I think people care a lot if we explain to them that the reason health care is unaffordable for today’s yuppies is because yesterday’s yuppies are receiving government health benefits that increase costs.

I think people care a lot if we explain to them that we are all Iris, today, right this minute, thanks to the market distortions associated with government debt. They pay up and satisfy the transversality conditions every time they go to the grocery store. That’s how they do it. That’s how they turn us all into Iris.

I actually brought up the capital question in response to Gene Callahan, who has been on the edges of this debate. I also brought up what I think to be the likely “law of supply” argument in favor of further debt on Catalan’s blog. However, these aren’t necessarily pertinent to this particular debate, they have been assumed out of the model– there’s nothing wrong in doing that in this particular debate.

I don’t know about that. It’s sort of like handing your car keys to a drunk six-year-old and then engaging in an ethical debate about when to teach children how to drive.

The real ethical question is how many other motorists on the highway you’ve imperiled by giving a drunk 1st-grader an automobile.

You can assume it out of the model, but what good would such a model be?

Perhaps I’m missing something, but the same could critique could be made about you – aren’t you assuming the drunk six year old into the model?

You’re giving us a “do you still beat your wife scenario?” here.

Are you suggesting that there are no market distortions associated with government debt, or are you merely complaining that I have “assumed” so?

Time to hop off the fence here, Daniel, and tell us what you really think.

I don’t know where you got that. Of course there are market distortions associated with government debt. I don’t think I’ve ever been anything like ambiguous about that.

Then, yes, you are probably missing something.

Daniel_Kuehn makes “missing something” into a competitive sport.

He actually believe in the SS accounting trick and defends it like it’s his mother.

It’s not a “trick” Silas. Either the federal government and OASDI are the same entity and it’s an internal transfer that doesn’t matter or they’re different entities and its an asset.

There’s no “trick” about it – I’m just trying to get you to talk about the issue consistently.

Yeah, that’s it! Every time he says something asinine, it’s just a suble trick to get me to think clearly!

That’s the thing, this isn’t an ethical or political question, it is an economic question. We’ve decided to isolate “debt” and assume all “other things being equal”, as well a define time periods quite strictly. No doubt, the things that you mention are quite important, but they’re not required for this particular exercise.

But then what is the point? Everyone agrees that transversality conditions exist, otherwise government debt is not possible. There’s nothing to model, it is an assumption of solvency, which is a necessary condition for the issuance of debt in the first place.

The idea of “who really pays” is really a question of: Is it the person who creates the debt, the person who pays off the debt, or is it a third case in which our resources are depleted gradually enough that we hardly notice that we’ve all paid. You’re telling me that the third case “has been assumed out of the model,” and I’m saying that this is precisely why the model fails.

Assume I jump out of a skyscraper to my death. Who suffers most: The street-sweeper, or the taxpayer who pays the street-sweeper. Assume my own death is immaterial.

Dude, I agree with you on many points. All that I am saying is that this particular model is far simpler than you’re making it out to be. You don’t need to even talk about price changes, capital, savings, etc to make it prove its point– that future generations are getting screwed.

Now, if we were talking about the implications for the capital structure, that would be a different story. But, we’re not.

Give me a break, I just got my ass handed to me by Landsburg a few weeks ago… I am treading softly.

😉

Actually, I just had a realization that this economy model was doomed to failure because it is entirely consumption based. So, no matter what you must increase consumption over every period into perpetuity. Without capital, you’re just using things up faster and faster (to service the debt), but you cannot necessarily produce more.

This model would make ANYBODY poorer, except for the first cohort (they benefit entirely).

Haha, fair enough! 😉

Hey Bob,

One of Steve’s man arguments is that in a real society a smart person can see what the government is doing and offset the transfer through extra savings that they can pass on through inheritance. How would that change your thought experiment?

One of Greg Ransom’s arguments is that it is impossible for a smart person to see through the fog of uncertainty created by the uncertainty of who and when folks will be left holding the bag when the government defaults, or who will end up being left with the tax burden as Peter and Paul and the man behind the tree continually entice politicians to repeatedly change the tax code so that the burden of taxes falls on someone else.

And that is just _one_ knowledge problem of many created by an ever growing debt regime handing over more and more control of resources to government planners operating outside of the realm of re-coordinated production and consumption plans driven by ever changing relative price signals and individual evaluators / relational valuers.

Glad to know you have my ignored concern covered and that you’ve already thought out the implications.

You keep saying this is “ignored” and in the Landsburg comment you particularly fault the “ivory tower” for ignoring this “layperson” concern – but I’m not sure why you say that.

Keynes discussed that at length, Barro discussed it in his 1974 paper and in the Macroeconomics Handbook article on debt, Elmendorf discusses it too (which says to me that what the two side have mentioned for decades is a firm enough part of what people think about that it made it into a Handbook chapter).

So cheer up – people haven’t ignored this!

Really? They’ve addressed that specific concern, which reverses Steve_Landsburg’s conclusion, but no one’s bringing it up?

Are you sure you’re reading both arguments (mine and what the economists you metnion are making) correctly? Do you have a quote?

Do you at least agree that this point is ignored in the context of this diablog?

It doesn’t reverse the conclusion, Silas – it’s an impact on the other direction. It renders the impact of any given action somewhat ambiguous (or – probably better to say “conditional”).

re: “Do you at least agree that this point is ignored in the context of this diablog?”

I do agree this dialog has abstracted from it – and for good reason. Krugman and Landsburg correct a lot of misconceptions of the layman and their corrective isn’t challenged by the discussion of uncertainty.

Nick thinks it’s a matter of whether it’s “impossible” to burden the future using debt, and he can do that without even getting into uncertainty too.

It doesn’t reverse the conclusion, Silas – it’s an impact on the other direction. It renders the impact of any given action somewhat ambiguous (or – probably better to say “conditional”).

No, it’s a reversal. All the way back to Steve_Landsburg’s Slate articles, he’s made clear that complaining about government debt is like complaining that I don’t mow my own lawn — it’s a purely voluntary burden. But if I actually prefer that government cut other spending programs to service its debt, then there is a burden (against my preference ranking) that I can’t personally remove.

That would *reverse* the argument that it’s purely a voluntary, removable burden, don’t you think?

I do agree this dialog has abstracted from it – and for good reason. Krugman and Landsburg correct a lot of misconceptions of the layman and their corrective isn’t challenged by the discussion of uncertainty.

I don’t consider that a good reason. If the layman is really concerned about X but phrases it as an argument about Y, it is not sufficient to show how ridiculous Y is — you need to follow it up with, “you, layman, should really be talking about X”.

For example, if the layman is worried about avalanches “because I don’t want to be crushed to death”, it’s no good to just say, “haha! You morons, avalanches kill people by trapping them under snow, away from resources, not from the crushing force!” You need to add, “I think what you’re really concerned about the *deprivation* aspect of avalanches, so please talk about that instead”.

Likewise, if the layman says, “I don’t like all this public debt because it burdens my grandchildren!” it’s simply not enough to say, “That can’t be the reason, because you can remove one kind of burden!” A complete response would be, “I think you’re really concerned about your ability to plan around future events.” — which no one is talking about.

I’m just pointing out this isn’t lost on people – it’s discussed. But it’s tough to make every single side-point in a blog post.

But it’s important to recognize that this isn’t something the layperson has picked up on that the ivory tower misses.

But the ivory tower is missing that the layman’s not missing it!

What are you talking about?

The whole reason the ivory tower is concerned about things like the issue you raise is that they know the layman isn’t missing it!

Ah, trying to have it both ways again? If economists are back to knowing that this is what laymen care about, why do they dismiss concerns about debt on the basis that laymen are really worried about something *else* on which they’re confused, which is exactly what Steve_Landsburg and Krugman have been arguing???

Silas –

People can be concerned about more than one thing.

Landsburg, Krugman, and I are saying that some of the biggest concerns people have are unjustified.

Other concerns are completely justified.

Then you should at least credit the layman with having valid concerns, and point out the correct way to voice them rather than just mock their expressive abilities. You know?

When did I ever mock laymen?

When have I ever denied they have legitimate concerns?

You have a very active imagination, Silas.

DK wrote:

When did I ever mock laymen?

There was the time you made a video in your bathroom with your shirt off…

Damn it Bob! – it took fourteen months to purge that image from my brain. This is going to cause permanent emotional scarring now.

@Daniel_Kuehn: Here, “you” means “those who are taking the Krugman/Landsburg tack”, and I’m definitely not imagining their trivialization of layman concerns!

Well you’re certainly holding your evidence tight to your chest Silas.

I’ve been following Krugman for years. I’ve seen no evidence for this.

Has he suggested that some of the ideas held by most laymen are wrong? Sure.

Most laymen consider at least some of the ideas held by most other laymen to be wrong.

So?

I think you’re taking a few examples that I guess bug you and extrapolating that more than is justified.

@Daniel_Kuehn: You’re holding your attention span pretty close to the present.

Krugman and Steve_Landsburg pretty clearly trivialized concerns about public debt. That’s what this whole conversation has centered on: whether their concerns are in fact trivial, or if it’s just a matter of semantics, etc.

Now you want to act like some kind of Rip van Winkle, waking up in the middle of the whole dispute and you want me to spell out everything that just happened because you don’t remember Krugman dismissing layman concerns about the debt.

Are you interested in a fruitful discussion, in which you challenge your ideas, or do you just like playing dunce in the hopes that no one will have enough patience to walk you through what just happened?

It’s okay, no one expects you to remember anything beyond the past two posts anyway.

“Nuh uh! I’ve believed that all along! Gosh, you guys are just so upset over nothing!”

They’ve addressed that specific concern, which reverses Steve_Landsburg’s conclusion, but no one’s bringing it up?

It’s clearly false to say that academic economics has ignored this result. It comes from one of the most basic, workhorse macro models that exists–the overlapping generations model. I mean, it’s like week 3, intro grad macro.

Everyone who is arguing that Krugman is wrong is doing so on the basis of a very well understood and widely recognised result in mainstream theory.

Really? They’ve addressed that specific concern, which reverses Steve_Landsburg’s conclusion, but no one’s bringing it up?

It’s clearly false to say that academic economics has ignored this result. It comes from one of the most well known workhorse models in macro–the overlapping generations model. I mean, it’s like week 3 introductory grad macro.

Everyone who is arguing that Krugman is wrong is doing so on the basis of a well known result in mainstream academic theory.

I like how this make picture clear how that government screws people when they are young and privileges people when they are old, systematically generation after generation.

It’s a “voluntary” transaction in the first instance — made possible by the promise of putting a gun in Iris’s face to collect the needed taxes when required, or the likelihood that someone, the hot potato holder, will be left robbed by the government when it defaults.

Well he actually doesn’t make it clear how the government does that – he just assumes it. You could switch the direction of the transfer with a keystroke.

And since young people generally become old people at some point, it’s somewhat unclear how this all nets out.

The debt burden increases in Bob’s model because the economy doesn’t grow. It doesn’t increase because the government screws the young.

The burden is bourne by the young because that’s the way that Bob sets up the model. The young are not burdened because of the nature of debt or the nature of government.

None of this informs me of anything but of your own concerns, Daniel, which I can predict in advance, and which often don’t reflect the real world.

How does your input here help me?

I don’t follow Greg. This has nothing to do with my “concerns”. I’m clarifying what Bob demonstrates vs. what he assumes, and I’m pointing out how his presentation here fits into the debate that’s been going on in the blogopshere.

I’m not sure if you’ve been following the debate or not, but we’ve been addressing a fairly specific question.

With some disagreement over what the right question is – something I remarked on early on about Rowe and Krugman’s slightly different emphases.

DK wrote:

And since young people generally become old people at some point, it’s somewhat unclear how this all nets out.

No, it’s crystal clear how it all nets out Daniel. That’s what a numerical example does. John in period 9 is indifferent, Iris is worse off, and everyone else gains.

The burden is bourne by the young because that’s the way that Bob sets up the model.

Yep that’s how counterexamples work.

But you’ve set it up as unsustainable. Presumably if it were sustainable (ie – if you took the liberty of assuming a growth rate) it would be fine. Nick notes this.

The other option is to fund this transfer with taxes, which makes the bargain less dependent on expectations of future growth rates.

Which is why I say it’s unclear whether transfers to old people are bad for young people who will become old people or not.

A single numerical example with certain very specific assumptions doesn’t prove anything, Bob. It’s just an example of one thing that would happen under certain specific conditions.

Daniel_Kuehn, that’s like saying, “Well of course a Ponzi scheme is going to screw someone over if you can’t keep snaring in new suckers. That says nothing about the *sustainable*, *respectable* Ponzi schemes.”

Couldn’t you also solve it (i.e. make it sustainable) by assuming a zero interest rate? After all, the economy is not growing. Bob assumes that people will ‘invest’ in the scheme because of the possibility of collecting interest, but they might also do it simply to defer consumption. An apple is perishable, but a bond presumably isn’t.

After all, the whole point is to fund old peoples’ retirement, when presumably they’d like not to work (or would be unable to do so).

Not only would that solve the problem, it is a quite realistic solution. We currently have negative real interest rates — people who buy government bonds today are essentially giving the government 20 apples in return for a promise of 19 at some point in the future. It is not so obvious why that debt would pose a burden on future generations.

re: “Yep that’s how counterexamples work.”

What exactly do you suppose you’re countering?

Nobody said a transfer from the young to the old (that gets nixed when Isis gets old) won’t burden the young. Of coruse it will. If someone has said it won’t and I’ve missed it, could you show me where they said that?

That’s not the issue. The issue is whether debt burdens future generations. Take a look at my very first comment on here. I think that answers that question.

But if the question is “does a transfer from young to old that gets canceled at some future date burden future generations” my answer is “Of course – who ever said otherwise?”

DK wrote: What exactly do you suppose you’re countering?

Re-read the 2nd paragraph of my post. I was crystal clear about what claim I was countering:

I am responding to Paul Krugman’s recent claims on why the standard political debate on the government debt is totally wrong-headed. (For a good summary of his position, see this NYT piece.) Specifically, Krugman conceded that if foreigners held U.S. government bonds in (say) 100 years, then those future American taxpayers would indeed be burdened by having to service the debt. However, Krugman said that empirically, Americans basically would “owe the debt to themselves” and so today’s deficits wouldn’t impose a burden, at least not for the simplistic reason that the average fan of Rush Limbaugh or Sean Hannity would believe.

DK wrote:

But if the question is “does a transfer from young to old that gets canceled at some future date burden future generations” my answer is “Of course – who ever said otherwise?”

Paul Krugman, Dean Baker, and a bunch of people in the comments at Nick Rowe’s blog, Lansdburg’s blog, and this blog.

Oh, and let’s not forget Bob Murphy in his textbook.

(With all of the above, we have to add, “…doesn’t burden them because of the fact that there are government IOUs being passed down.”)

I don’t think your interpretation of PK et al. is correct. Paul Krugman has said on numerous occasions he thinks debt can be a problem if it grows faster than the economy over the long term. Meanwhile in comments in his post Nick Rowe has admitted that his model of debt burdening future generations does not apply to situations where debt doesn’t grow faster than the GDP. So the disagreement is a conceptual one, about whether situations like the one in Greece are best thought of as future production being consumed in the past, or a distributional problem within the future. I favor the PK view here, as it better fits with the problem of underproduction: if we have to work now to pay for the consumption of the past, then why are we short on work? Why is unemployment so high in Greece? Shouldn’t they have to work now harder than ever? A distributional explanation would be the Greeks lack the money to pay each other to work and those with the money (roughly speaking, the Germans) don’t need the Greeks to work.

You have to keep in mind what Krugman is countering. First of all it is a common layman mistake to believe that some day we will have to pay off our debt in full, and that is just wrong. It would be a terrible idea to do that even if we could, and it has gone badly on the very few occasions we’ve tried. If the layman view that government debt borrows from the future were generally correct, then government debt would always be a present benefit and a future negative, but that’s wrong on both counts; borrowing to spend in a full employment economy can have crowding out effects that are bad for private investment in the present, and government borrowing in a depressed economy can be the best thing for both the present and the future. And Krugman is countering the view that we should be engaging in austerity now in the US. Yes, there are situations where debt can create a bad situation in the future and Krugman may overstate the generality of his way of looking at debt, but his view is much more relevant to the present day than your example is. The present situation is one where the government borrows 20 apples today in exchange for a promise of 19 in the future, where apples are being left unpicked due to a shortage of demand, and where we are nowhere near any level of debt that has gotten a country with debt in its own currency in any trouble.

Murphy,

I think I stumbled across an alternative way to think about your awesome charts so that those who still think Krugman is right despite your explanations, can understand that you’re right if you use this explanation:

http://consultingbyrpm.com/blog/2012/01/future-generations-will-be-indebted-to-me-for-the-clarity-of-this-exposition.html#comment-30933

“LANDSBURG: Krugman has a good take on this issue, and I would add just one caveat: Guns don’t kill people, bullets do.”

I think he might also argue that because of Ricardian Equivalence society would not need to punish the gunman because their families would simply start some offsetting procreation activities.

Ballistics is not a morality play.

“In closing, here’s an analogy of the positions:

LAYPERSON: Whoa, that nutjob went into a restaurant and killed 5 people with a gun.

KRUGMAN: You idiot, you should study physics. Energy is always conserved.

LANDSBURG: Krugman has a good take on this issue, and I would add just one caveat: Guns don’t kill people, bullets do.”

Not only is this analogy fun, you made it possible to work in the whole ‘mainstream economics as physics and it omits what is important’-critique there.

Bob: You’ve observed that if govt debt grows faster than the real rate of growth (which, in your example, is zero), then there must eventually be a default, which constitutes a redistribution away from the bondholders. I daresay everyone already knows this.

That’s not very helpful if they consistently fail to acknowledge when they’re on an unsustainable path 😛

Steve wrote:

Bob: You’ve observed that if govt debt grows faster than the real rate of growth (which, in your example, is zero), then there must eventually be a default, which constitutes a redistribution away from the bondholders. I daresay everyone already knows this.

Steve, this is one of the rare times where you are simply wrong. My example above contains no government default, and no redistributive taxation (within a given period). The government taxes Iris 100 apples, then hands them right back to her. And yet, she is clearly hurt by the whole thing.

So no, your attempt to summarize my model here is simply wrong. I am stunned, because normally I think you make true statements that are talking about things I don’t want to talk about.

Isn’t what happened to Iris functionally equivalent to a default? Why did the government tax her instead of issuing another bond?

I think because that’s the framework Krugman set up.

They tried to issue the bond but Young John thought it looked like a scam and said, “no thanks”.

Voluntary remember? So it can’t be a problem if someone says “no”.

The parameters of the scenario are that everyone prefers deferred future consumption, so Young John would buy the bond if offered. That’s why I’m wondering why he ended in period 9.

I also don’t understand why the interest rate keeps going up in each period, if 10% were the global interest rate, shouldn’t the progression (rounding up to whole apples) look like (11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 24, 27) ? Not sure why rates have spiked at the end

The other parameter is that people don’t like highly unbalanced consumption, and if you think about it there comes a point where the level of unbalance between young consumption and old consumption simply is no longer viable (if for no other reason than a person can’t eat nothing for half their life).

Bob doesn’t explicitly state when that happens but if it didn’t break at John, it would break anyhow a few steps further down the line. Maybe John should have bought a few bonds (up to the limit of unbalance that he was willing to tolerate), so Iris would have not taken such a big hit. I agree with your progression at constant interest rate, but does that significantly change the example?

Well, if there is a tipping point, it would have to be revealed in period 1. If young people are willing to buy a bond of any size, then the only constraint is the demand of the elderly, which they would max out right away. I doubt this hypothetical society could get to the point where the elderly are flooded with too many apples, cursing their ancestors for that apple bond from ten generations ago. I would guess that future demand for “goodies” would take the form of a mix of present dat taxation and debt, so the total size of the apple debt remains constant through time.

Just sketching it out quickly on a spreadsheet (and rounding the interest to nearest whole apple) a 10% rate allows you to keep the scheme going for 26 generations before young consumption hits negative apples.

I’m surprised by that result actually, I thought it would crash and burn a lot sooner. If you set a more reasonable minimum limit (e.g. 50 apples) then at 10% interest you still get 18 generations before the government needs to tax anyone. I’m beginning to see how dangerous this really is. I mean, who really honestly can say they care about what happens 18 generations down the line?

If you allow for people buying some bonds, but not sufficient to cover the whole government debt, then it reaches equilibrium where government is taxing just enough to cover the interest on the debt (implying that in real terms, there is no interest paid on the loans).

That is to say, the real system growth rate comes to equal the interest rate — either sharply (when one generation decides not to play) or gently (if each generation plays only so much).

Strangely, when I tinkered a bit more with it, while real interest is still getting paid (i.e. in the early generations) it is advantageous for each individual to lend to the government (they eat more than they produce). However, once the system reaches equilibrium, a generation that buys less bonds can do slightly better, depending on who the government decides to tax in compensation for that (e.g. the young can toss some tax burden onto the old). This perverse incentive makes me think it will never really be able to gently reach equilibrium. Once people understand that no real interest is getting paid, it will accelerate toward default.

When you put banking and guns together… it does have a nasty side to it.

Ben Kennedy, good catch. The reason I had the tax payment cap out at 50% of GDP (instead of 100%) is that I was thinking the person in the prior period wouldn’t buy a bond, knowing that the revenue to pay it off would come out of his own apple crop the next period.

But, I’m already violating that assumption by having Iris get paid off from the gov’t taxing her.

So you’re right, I should have had the debt grow to 100% of GDP before the govt decided to pay it off.

“I should have had the debt grow to 100% of GDP before the govt decided to pay it off.”

I detest expressions of the form “debt is x% of GDP” because as someone with a physics background, economists’ sloppiness with units is infuriating. In the end of your model, debt is half of one period’s worth of GDP, but a period is half of a human lifetime, or about 35 years, so debt at that point is something like 1750% of a year’s worth of GDP, which is the debt/GDP “ratio” normally quoted. Investor confidence would probably tank well before that point.

I think the example also needs a summary on what each person consumed (given that everyone produces 200):

Al: 210

Bob: 201

Christy: 202

Dave: 203

Eddy: 204

Frank: 206

George: 211

Hank: 222

Iris: 141

John: 200

So we manage to get 8 consecutive generations of people eating more food than is even produced, in a system where food cannot be stored between periods. If you asked someone like Old George if there was a problem, he would say, “I live better then may parents and my kids will live better than me,” and he would be completely correct. How could there be a problem?

If you ask a Keynesian they would say, “John was selfish and messed it all up, and he ended up making Iris worse off and himself worse off as well. If John had played the game, both he and Iris would have got more than 200 apples.”

Dude –

1. That last point has nothing to do with Keynesianism

2. More importantly – YOU ARE MIXING TIME PERIODS!. If you look at each time period the same amount of income is being consumed. The exact same – whether there’s debt or not.

Krugman is right.

If you do what you do here, and look at who consumes the income, some people do bear more of a burden than others – but each period earns and consumes the same. Krugman is right. Bob demonstrates Krugman’s point.

1. It is what a Keynesian would say. That is separate from Keynesian theory.

2. He isn’t mixing time periods. Read what he said. He INTENDED to tally the total consumption OF EACH INDIVIDUAL in their lifetimes. That means he’s adding column data, not row data.

Krugman is wrong.

You keep believing the erroneous “But Bob, total consumption remains 200 per period, even when the governments taxes Iris in period 9 to pay off the debt! Clearly it MUST only be a redistribution story. Only if BOTH Iris and John “collectively” consume less than 200 apples, will Krugman be wrong and you’d be right.”

The error you are making is that you are not looking correctly at Bob’s argument.

In the first chart, look at Iris’ consumption pattern. It’s (100,100). 100 apples for her young self, and 100 apples for her old self.

In the second chart, the one with government borrowing and deficits, look at Iris’ consumption pattern. It’s (41,100). 41 apples for her young self, and 100 apples for her old self.

For John on the other hand, his consumption is the same in both scenarios, 100 apples.

Now, here’s the outcome: John is no worse and no better off. Iris however is WORSE OFF with government borrowing and deficits, because instead of (100,100), she consumes (41,100).

John consuming the same and Iris consuming less means “collectively”, John and Iris consume less AS INDIVIDUALS.

DON’T look at the time periods only. Look at the individuals and their consumption patterns. After all, Iris isn’t born in period 9. She is born in period 8. She lives in period 8 and 9.

Since time always goes forward, Bob’s argument is that because INDIVIDUAL PEOPLE will end up consuming less, WHILE NOBODY ELSE IS CONSUMING MORE, then it follows that there is a “collective” reduction in consumption, again FOR THE INDIVIDUALS LOOKED AT SEPARATELY.

If you think this logic is “strange”, it’s because you are not taking time into account. You, like Krugman, mistakenly believe that we should ONLY take into account a cross sectional time comparison.

I think an analogy will help you here:

Suppose you see two people, one old and one young person, standing in a room, and you’re standing outside the room. You are separated by a door. Once a year that door opens for a day, just long enough for you to see the twins eating 200 apples total, and then the door shuts again for a year.

Suppose I am in that room all the time, so I see the FULL story of what’s going in that room, while you see only the consumption that two people engage in when the door opens for that one day each year.

This is your logic: You believe that as long as you see an old person and a young person eating a total 200 apples each year, then “collectively” they cannot be “worse off” to you.

From my perspective of someone being inside the room all the time, this is what is going on:

Each year, the young person lends me a sum of apples, and then I pay them back plus interest when they become old the next year. In order to pay them back plus interest when they are old, I again borrow what I owe, but this time from the new young person who was born that period. After I borrow and spend, the old person and young person consume their apples, then the old person dies while a new young person is born.

I repeat this each year.

Standing outside the door, each time the door opens once per year, all you see are two people, one young and one old, consuming 200 apples total.

So far so good. Now as far as you know, the young and old person in the room cannot be worse off as long as you see a total 200 apples consumed each time the door opens. So you believe that they are no worse off “collectively.

Now suppose in years 8 and 9, I do the following behind close doors:

In year 8, I do like I always do for one year. I borrow from the young person. I also give apples to the old person (whom I borrowed from in year 7 when they were young).

After I do this, the door opens, and sure enough, you see a total 200 apples being consumed. You think everything is fine. The door then shuts again.

Now let’s go to year 9. Behind closes doors, this is what I do (which you don’t see):

Instead of borrowing from the new young person and paying back the now old person, I just pay back the old person what I borrowed from them when they were young. In order to pay them back, guess what I do? I don’t borrow from the new young person, but rather I point a gun at the old person and demand that they give me a portion of their 100 tree yearly production. Once they pay me those apples, I then use those apples to “pay them back plus interest”. The new young person is left alone, and does not lend any apples to me.

After this happens, the door again opens. And once again, you observe a total of 200 apples being consumed “collectively” by two people, one young and one old, standing in the room.

Now, if you had to guess, you’d say that collectively they are no worse off.

But I KNOW, as someone who is standing in the room, that they are “collectively” worse off for the simple fact that the old person is on net worse off, while the young person is on net unaffected.

In a kind of Pareto understanding, if one person is worse off while everyone else is unchanged, then that is a “collective” decline, despite the fact that you see the same TOTAL apples being consumed when the door opens.

The “missing link” that Murphy did not mention but is important is that you have to think of period 9 as a time of introducing a coercive element where instead of paying back old lenders and borrowing from new lenders, I also TAKE apples from people. In the case of period 9, the old person is net worse off by however many apples I took from them.

EVEN IF I then give those apples right back them, to settle my debt, after which the door then opens and you see a total of 200 apples being consumed again, BEHIND closed doors since you can’t see you sort of always “expected” that there would be a new lender there to lend to me so that I then pay off the old person. You aren’t noticing that even if there are 200 apples consumed each time the door opens, the 200 apples is in fact a result of events occurring OVER TIME, not just cross sectionally. This is why Bob’s charts are ingenious and why so many don’t get it.

When the door opens in year 9, it’s like you just walked into a crime scene, but because you don’t see a reduction in the 200 total apples being consumed, YOU INCORRECTLY SURMISED THAT ONLY REDISTRIBUTION COULD HAVE POSSIBLY TAKEN PLACE.

You incorrectly believe that young John is even involved in year 9. He isn’t. John is NOT A PART OF THE SAMPLE. He just produced 100 apples on his own, and he consumed 100 apples. He has no relevance to why “everyone”, meaning just Iris, is worse off.

This example is not only ingenious for the above, but it is also a clever “test” to show whether someone thinks like a Keynesian or whether they think like an economist. Those like you who implicitly depend on there always being new suckers who produce enough resources for profligate government deficits and spending, fail to understand that “collectives” don’t include those who aren’t even in the government borrowing and lending game, but are expected to continue to lend to government to provide enough resources to pay back old lenders. It’s a classic Ponzi scheme that results in a net loss when the scheme collapses and the Ponzi schemer starts to steal from his own clients to pay them back.

You see the same consumption cross sectionally and incorrectly believe it can only ever be a redistribution story. Bob has proven Krugman wrong. There is a net loss to individuals, AND to the collective.

Daniel Kuehn, people do mix time periods, I plan for my retirement, what do you do?

I’m merely adding up the total apples that each person gets in their lifespan, and if EVERY person is eating more than they consume then this CANNOT end well. I’m totally surprised you have difficulty with this sort of analysis.

More interesting is the question of how long it can keep going and what sort of event brings it to a stop.

MF, you really have to learn to write a short pithy reply… but I think what you have said is correct. We need a codeword to distinguish Keynesian theory from Keynesian practice, I’m up for suggestions.

Ahh crap, “eating more than they produce”… you know what I mean

Actually, if the government made different taxation decisions when they switched to taxation, Iris could have had 200 apples over her lifetime, and every generation that followed could have that too.

Obviously this example involves an intergenerational compact that cannot be maintained over time, but the decision of the government in the end to completely reverse it is an arbitrary one and it is this decision that creates most of the perceived burden. After all, if the debt guaranteed such a burden on the future, why is John able to eat way better than Iris did as a kid? The debt did not cause the government to tax Iris instead of John; Bob Murphy did.

I think this is missing Krugman’s point because he is thinking in terms of groups. He would define “our children” as all the people alive at some point in the future – a future collective. To know if a collective were suffering, we would look at aggregate apple consumption. He does not care about redistribution within the collective (or would solve it with offsetting redistribution). But because they have consumed the same as us in year one, so collectively they are not suffering any more than we are.

However, the examples show that even if they are “apples we owe ourselves”, there can be great injustice as those debts are retired. So while our children collectively may not be poorer, some children will definitely be poorer because of the decisions made by their ancestors.

Exactly.

In “events with no government” there exist 200 apples in period 8.

in “events with government” there exist 200 apples in period 8.

The debt DO NOT impose a burden, in the sence that they collectively get to consume less in period 8.

The debt DO case redistribution between people in e.g. period 8, given no additional actions.

This can however, anytime, be solved through taxation – so – the distribution in e,g, period 8 is still whatever the people living in period 8 wants it to be (the second welfare theorem).

Do we need to call for an ambulance for you yet, Bob ?

Rob wrote:

Do we need to call for an ambulance for you yet, Bob ?

At first that was my reaction, Rob, but now I am actually delighted all the more so. Three days ago, I thought, “Wow, this stuff is so subtle that even though Boudreaux (relying on Buchanan) and Nick Rowe are spelling it all out for everybody, it took me a day to see it, and I can tell lots of other people still have no clue why their intuition is failing them on this stuff.”

But now I realize, “Wow! This stuff is so subtle, that even when I give an actual numerical example demonstrating why their intuition is wrong, people are still clinging to it like a crack habit.”

This isn’t a Monty Hall Problem where people are denying a mathematical truth. Rather, it’s a different of opinion on the definition of “suffering children” means. If it means “some children will suffer”, this example shows it well – Iris is a big loser due to what essential amounts to a default on her bond. If “suffering children” means ‘in aggregate, some children will suffer”, then Iris’s personal suffering is offset by someone’s benefit, its a wash, and collectively “our children” are not suffering at all.

Think of two statements. First, “children are starving in Africa”. This evokes the sadness of widespread famine and mass starvation, where all children in an area are suffering due to hunger, and all children are affected. Now consider “children are starving in America” – same statement, different location. This makes me think of homeless children perhaps, or people in extreme rural poverty. However it does really mean the same thing as “children are starving in Africa” as it is not a statement that there is famine in America. The first sense (collective) is the Krugman sense, so one could say “children are (collectively) starving in Africa”. The second sense is the individual harm sense (like Iris) – “(some specific) children are starving in America”. The words are the same, but the meanings are quite different, in the same “burden on our children” has different meanings depending on who is using it.

So when it comes to the debt, Krugman is saying that the retiring it is not going to be a collective burden – the “Africa” sense. We know this because his analogy to the situation is a family paying off a mortgage. When this occurs, family consumption drops, and people most impose austerity to meet the payments. He is saying “there won’t be national austerity in the future to pay of today’s national debt”. I think this pretty much has to be true, since you can’t send apples through time. Yes there are poor individual losers like Iris, but I’m sure Krugman would find some other way to fix that specific problem by further redistribution interventions – it is just not on his radar as an issue..

Most of this debate could be resolved not with apple analogies, but to specifically define what “burden on our children’ actually means in more precise language.

As a layperson, I think there is a different between the statements “children are starving in Africa” where

Ignore last paragraph, was at secretly at end of buffer when I clicked – off topic, I’d love a “preview” button that most blogs seem to have

You know what this post needs? It needs Gene Callahan to comment and tell everyone how they are all wrong, and then throw in some rationale on why everyone was wrong that no one but Gene would understand. Yep, that’s what’s missing!

“Gene Callahan to comment and tell everyone how they are all wrong…”

So amusing, Chris. Except I don’t think you can’t point to a single example of me doing anything like that. On this topic, for instance, Steve Landsburg and Paul Krugman (and many others) hold the same view as me. Or, for instance, when I say you anarchists (assuming you are one) here are wrong, what I’m saying is that a fringe .5% is wrong, and 99.5% of people are correct, and huge numbers of people besides me see why this is so.

So you’re just being an ass, right?

How interesting that Gene Callahan can be a smart ass, be condescending in his comments, call people mentally retarded, and then when someone reciprocates, he can’t handle it.

“So you’re just being an ass, right?”

Imitation is the highest form of flattery.

Richie, the issue here is, “Can Chris (or now you) actually point to somewhere I actually have done what Chris said I do?”

Chris did not call me an ass. (That I am, I readily grant you.) He said something quite specific: “Gene Callahan does X.” I said he can’t point to ANY instances of me doing X, and he is an ass for accusing me of something I don’t do. Your response is essentially “Ha, ha, you’re an ass too!”

So, Richie, would you like to defend Chris’s accusation by pointing to some instance of me doing what he said, or are you just being an ass as well?

Thanks Bob!

Yes, that is nice and clear. I just left a comment on another blog, suggesting the author look at this post. he had read my original post and couldn’t figure out where the new apples were coming from! It’s all clear in your exposition.

Slightly off-topic, but only slightly:

The basic message that most readers will get from Paul Krugman’s posts is, I think, this: “Don’t feel sad about the national debt, because it isn’t really a liability. We owe it to ourselves.”.

Now, what is needed is for someone to write the mirror image post, saying: “Don’t feel happy about the government bonds backing your pension plan and bank account, because they aren’t really an asset. We are owed them by ourselves.”

Nick Rowe wrote:

Yes, that is nice and clear. I just left a comment on another blog, suggesting the author look at this post. he had read my original post and couldn’t figure out where the new apples were coming from! It’s all clear in your exposition.

Thanks Nick. You’ll note that the author in question–Gene Callahan–not only has refused to apologize, but (look at his comments here) is still maintaining that you and I are ignoring the brilliant insights of Krugman et al.

Landsburg, are you still checking in here? Do you see how not “easy” this stuff is? Nick gave the solution, Gene Callahan (on his blog) said Nick’s example was “logically incoherent,” then I spelled out Nick’s example in crystal clear form, and Gene still doesn’t see it. Also, in case you don’t know him, I will vouch for Gene and say he’s not stupid. In fact, in his past career he was a computer programmer for a firm on Wall St (?). It’s not like Gene has trouble understanding numbers or logical arguments, and yet here he literally can’t see it (yet).

To repeat, Steve, I’m not saying your particular observations have been false on all this stuff. (In fact, when I get time later today I will go back to your blog and retract where I said I thought some of your summary statements were wrong. Now, I’m pretty sure they are right–but they are extremely misleading for those, like Gene, Krugman, Dean Baker, and half the people commenting on our blogs.)

[URL=http://www.directupload.net][IMG]http://s14.directupload.net/images/120107/bqbx7uv2.jpg[/IMG][/URL]

Note how this society borrowed their kids rich!

Bob, you are mistating the argument Landsburg and I offer against your examples, and, once you have thus mis-stated it, it is pretty easy to knock it down.

Gene Callahan wrote:

Bob, you are mistating the argument Landsburg and I offer against your examples, and, once you have thus mis-stated it, it is pretty easy to knock it down.

Hey everybody, Gene and I need your help to referee our dispute. I made two claims about Gene’s position:

(1) He said Nick Rowe’s model was “logically incoherent.”

(2) He has refused to apologize for this statement, and continues to maintain that Krugman and Gene have been right all along on this.

I think we can all agree I fairly characterized point (1), since that is the first sentence in Gene’s post.

So now, the only question is, do people agree with my assessment that Gene doesn’t seem to be admitting he has made some mistakes thus far in this debate? (Yes, Gene on his blog was a teensy bit accommodating vis-a-vis Nick Rowe, along the lines of, “Rowe is still totally wrong, but now I more clearly understand why he is wrong than my initial reaction suggested.”)

Murphy right. Callahan wrong. Only time I ever credit Murphy because I Sumner Fan.

“Hey everybody, Gene and I need your help to referee our dispute. I made two claims about Gene’s position:

(1) He said Nick Rowe’s model was “logically incoherent.”

(2) He has refused to apologize for this statement, and continues to maintain that Krugman and Gene have been right all along on this.”

That wasn’t even what I was talking about in my comment. I was saying that the analysis that Landsburg and I gave of your initial point was identical (as Nick Rowe pointed out on my blog), and that you have not correctly grokked that position. I now think maybe you have, but are doing a “You’re correct, but still wrong” dance.

If agents have perfect foresight they will never buy a bond which can only be retired by a lumpsum tax on them. If young Iris doesn’t buy the bond, there is no reason for the Govt to tax her late on to retire the bond. In this model, Govt taxes are impredicatively determined by the bond buyer.

Why would Iris suffer from ‘bond illusion’?

The Rational Expectations soln is that there is lending and borrowing between cohorts for consumption smoothing etc but if the Govt tries to intermediate this it either has to do exactly what the market would have done or find its own credit is in the crapper.

Doc, thanks for the crystal clear charts and explanations. Makes sense to me.

You are blessed to have a good mind and thick skin (unlike, say, Gary North) to put up with some of the repetitive bickering here.

By issuing the debt, the government made it look as if there was more wealth than there really was. After several generations, the interest on the debt becomes greater than GDP (a claim on more apples than exist). The government extinguishes the debt through taxation. This is not exactly a net burden on the population at the time when it happens, although it may feel like it – because that wealth never existed in the first place. It looks like a loss because trees plus government bonds get converted into just trees.

It may be worth trying to see what the difference would be if the money was taxed instead. First, the money would come from everyone, rather than just lenders. (This difference isn’t apparent in the example.) The government’s demand for loans probably pushes up the rate of interest. I think that by borrowing instead of taxing, the government favours lenders over non-lenders.

C’mon, Gene, it was just a joke! Yes, I was “being an ass”, I learned how to from reading this blog called Crash Landing! Ha!

The dispute really arises because one set of people is looking at the consumption of the people living at any one time, which is constant at 200 apples, no matter what, and the other set of people is looking at the lifetime consumption of any single person in a “generation”, which of course craters when the game ends.

If you take “our children” to mean all people being alive at the same time, then of course the existence of the debt does *not* place any burden on them in the aggregate, since their total consumption is always the same. In any time period, all the “debt” does is to change the distribution of the consumption among the people alive at that time.

I believe this is the more useful way to think about this, because the real question is one of distribution of all consumption goods at any one point in time. In this model, the question of redistribution is of course pointless, since everybody has an apple tree that always produces 100 apples. Everybody can consume, no redistribution necessary. In the real world, some people are of course children or retired and do not work, so a question of distribution of consumption always arises, completely independent of the mechanism.

This means that the debt is then only one possible mechanism to achieve this redistribution that is necessary under any circumstances. There is no plausible scenario under which a working generation is not required to forgo some consumption for the benefit of the retired and the young.

If the world does not end, any generation will have to be “taxed” in order to support the people who are unable to work, so in a real world sense, the redistribution game can never end. In that sense, I would even claim that the debt is not a burden in a “vertical” sense, for the lifetime consumption, because contrary to this example, there will always be an obligation to support the old. Does anybody doubt this? And everything else is investment risk, whether you invest in stock or government debt, if there is a default, you are left holding the bag anyway….

[…] All this shows that debt burdens don’t magically disappear when we pass them along to future generations. You can kick the proverbial can down the road, but the road has to eventually end somewhere. (Bob Murphy provides some other helpful numerical examples here and here). […]

[…] All this shows that debt burdens don’t magically disappear when we pass them along to future generations. You can kick the proverbial can down the road, but the road has to eventually end somewhere. (Bob Murphy provides some other helpful numerical examples here and here). […]