I Took Down My Brad DeLong vs. John Cochrane Post

Well shoot, I still think Brad DeLong was very unfair to John Cochrane when he said that in his Cochrane’s WSJ op ed, Cochrane “draws this curve:” and then posts a curve that DELONG drew, not Cochrane. That’s the upfront, gripping part of the post, and when I first read it, I too was stunned that Cochrane had (allegedly) done that.

Later on in the post, DeLong posts computer code and says “Play with the R-code if you want to see how much a more flexible functional form wants to say that the U.S. has the optimal “Business Climate.” I confess I didn’t look very carefully at this. I thought DeLong was saying (I’m paraphrasing), “Even if you use other functional forms, you can’t make the ‘best-fit’ line go through the point Cochrane needs, if you’re using levels of per capita income on the y-axis.”

But alas, I should’ve looked more carefully. DeLong at that point (again, the bottom of his post) *does* finally switch to log income, which is what Cochrane actually used in his WSJ post. (Cochrane explains why he did that, in his blog response to DeLong.)

So, I still would’ve had a nice little blog post had I looked more carefully at what DeLong did with that code. To wit: Rather than simply reproduce the actual graph Cochrane used, instead DeLong (a) first tells us he drew a graph that he did not, and (b) then gropes around with computer code to make it work better (?), leading the reader to believe that DeLong is searching for a way to figure out where Cochrane could possibly be coming from.

So anyway, I took down the first post, because I had so badly misunderstood that component about the computer code that it was easier just to remove it. My apologies for the confusion I added.

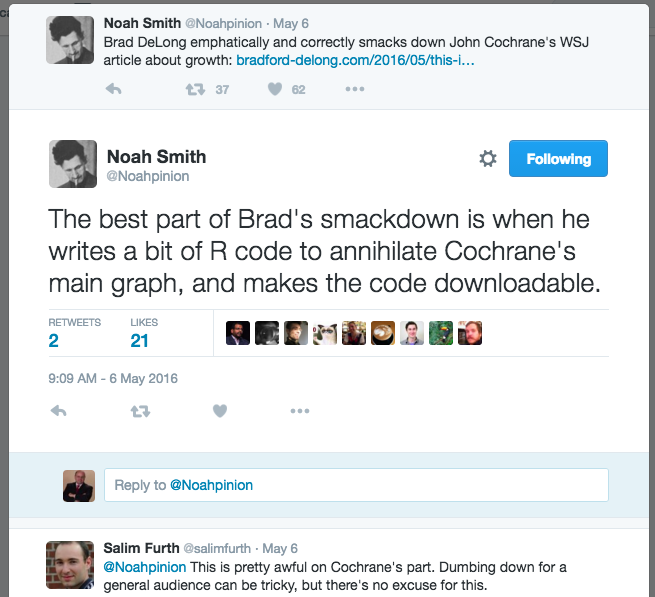

Last thing: I realize it sounds like I’m making excuses, but guys, cut me some slack. I don’t read DeLong’s blog anymore, or Cochrane’s for that matter. The whole reason I even stumbled on this dispute was that I (foolishly) follow Noah Smith on twitter, and this is the tweet that alerted me to DeLong’s blog post:

So I went into this thinking–and Salim Furth confirmed–that DeLong had eviscerated Cochrane, both logically and with computer code. This is why I didn’t carefully parse DeLong’s computer code to see that far from writing code that “annihilates Cochrane’s main graph,” I think actually what happened is that DeLong’s code came closer to explaining Cochrane’s main graph (though still not sure what he was doing with it–I think Daniel Kuehn and Noah Smith came to opposite conclusions about what DeLong was demonstrating with that code).

What did we learn, kids?

#1) Never be really smug, because in case you make an innocent mistake you end up looking like an idiot. (I’m referring to myself in the previous post.)

#2) Economists are dangerous.

#3) I need to unfollow Noah Smith on Twitter. I’ve known this for a while but this is pushing me to act. I’ve hit rock bottom.

#4) I made Daniel Kuehn’s weekend.

In a very vague sense I might agree with Noah, but you’re right I don’t think the code demonstrates Cochrane’s line is wrong in any literal sense. Indeed the very first thing the code does is reproduce Cochrane! (And the second thing it does is show that the second-order polynomial is pretty close to Cochrane too).

What I think he’s doing with the code is showing that a less restrictive functional form does not show income per capita exploding with deregulation. I think this is what DeLong intends to do AND I think it’s what he accomplishes with it.

But what I said on the last post and I’ll say again is that I think DeLong is really burying the lede (and he sorta conceded this to me when I told him that). Maybe Cochrane’s specification is bad maybe not. I’m finishing off my dissertation today which fits a linear model to logged data so I hope it’s not all that crazy because that’s all Cochrane does. If his specification is not ideal, fine, but that’s hardly the most salient point here. There are two really big points. The first of which is the most important but DeLong just leaves implicit, the second he does an OK job addressing:

1. Cochrane does a cringeworthy projection out of sample that is really, really, really bad practice.

2. Cochrane treats the relationship as causal which is pretty questionable in this case.

If you don’t agree with me that (after abiding by 1 and 2 above) specification is a non-issue, just look at DeLong’s plots. His preferred fourth order polynomial and Cochrane’s linear model are for all intents and purposes identical IF YOU STAY IN-SAMPLE.

Daniel,

You know we love you here, and it’s because of lines like this:

In a very vague sense I might agree with Noah, but you’re right I don’t think the code demonstrates Cochrane’s line is wrong in any literal sense.

So you very vaguely agree that DeLong’s code annihilated Cochrane’s graph, even though it doesn’t literally demonstrate that Cochrane did anything wrong?

I didn’t mean it to sound so crazy. I agree broadly that DeLong annihilated Cochrane and the code was a part of that, but as far as the code alone on its own terms you’re right, I take a completely different view from Noah. Nothing different from what I said in the rest of the post. The takeaway ought to be that yes you’re right, Noah and I see the significance of the code very differently.

Daniel, you said “What I think he’s doing with the code is showing that a less restrictive functional form does not show income per capita exploding with deregulation. I think this is what DeLong intends to do AND I think it’s what he accomplishes with it.” So you do agree with Noah Smith’s interpretation of what Delong is doing, you just differ on how devastating it is compared to other parts of Delong’s critique, right?

I suppose that’s a good way to put it. I disagree with Noah on what constitutes annihilating Cochrane. I really don’t think this specification thing is a big deal at all UNLESS you project out of sample and assume causality. And that’s precisely what you shouldn’t do. And if you don’t do that the specification tweaking really doesn’t matter at all.

Well, if hypothetically we did live in a Universe where economic growth was completely causally determined by business friendliness, and we were confident that things would perform well out of sample, then you agree that Cochrane’s choice of a linear fit would be a major problem, right?

If we lived in a universe where we could project out of sample then getting the specification right would be essential. But it is precisely because we literally don’t have the data to get the specification right out of sample that we live in universe where we can’t project out of sample.

OK, we’re on the same page.

Correct… if only Brad had explained it that way. Flipping back and forth between log axis and linear axis just muddied up the water.

I might add that if you are going to propose a policy that takes you away from where you don’t want to be, and into somewhere you haven’t been before… then extrapolation is a requirement. Otherwise the only policy you get is halfway between what two other countries are doing. The Keynesian stimulus of 2009/2010 was also well and truly out of sample, as was the massive QE money printing. Right out of the ballpark.

To address your last point. If I play with the coefficients I think I can make a 124537768845566644390106 degree polynomial fit very closely to a linear model as long as we stay in sample. So that proves nothing.

As for all these plots. Have I missed something? Isn’t it a bit crazy to be doing this in the first place? Y’all assume a score of 90 is 50% higher than a score of 60. That’s ratio data. That’s a strong claim. Nobody cited questions treating the friendliness score as ratio data. Do economists routinely treat such numbers as interval or ratio data? This is nuts. If I give Trump a twerp score of 90 and Murphy a score of 60 it would be wrong to conclude Trump is 50% twerpier, right? You wouldn’t do regressions on such numbers would you?

Can you explain the point of your first paragraph? I think you’re missing my point. My point is precisely that any of these polynomials fit really well in sample, including Cochrane’s first order polynomial. So I agree with you. That’s my whole point.

Your ratio data point doesn’t matter. Nobody is interpreting it that way and it doesn’t matter for the statistics. It DOES matter for the interpretation but nobody is putting an interpretation on what X number of points means.

I don’t know that we’ve ever seen Kuehn vs. Craw before?

I haven’t seen him this wrong before.

Then again, I haven’t often looked.

😉

Of course it matters. You are using these scores as if they were actual numbers not labels. When you do the damn R code you are making assumptions about what operations are sensible on the data.

Look, there are different kinds of data. Some is just a number as a label. choose 1 for the pool, 2 for the track, 3 for the main office, 4 for help. Would you do regression on these numbers?

Some data is just ordinal. Callahan is #1 on the rude list, LK is #2. Would you do regressions on that?

Moving up we can have interval and ratio data. I do assume you know that so I won’t explain them. To do regressions sensibly you need certain kinds of data. As true for order 4 polynomials as for order 1. [Probably even truer since order 1 will respect ordinals, right?]

So when you say “nobody is interpreting it that way” you can only be right if by nobody you mean “everybody doing regressions.”

I created a plot. It shows Y/P against my assessment of the attractiveness of the Starbucks nearest the nation capital. Coincidentally it is *exactly the same plot* as we are discussing. Wild huh?

It would be silly I think to treat my assessment as a measurement of a real objective thing, in ratio data terms. Have long raging deabted with R code posted. Right? I mean, wouldn’t that look silly?

You are completely correct… but it does give a nice looking scatter with a clearly visible general trend to it.

If your Starbucks assessment had been done without any reference to other factors (i.e. if you hadn’t just copied this data) and it gave a good looking trend on a scatter graph, I’d say there’s probably something to it.

But yeah, don’t read too much into it… it’s only Sociologist statistics.

Economists are only dangerous if you pay attention to us 🙂

Sometimes not even then!

Still seems to me DeLong was being intentionally dishonest and misleading

That’s not a cool feeling. Sorry Bob.

I read both posts and think you’re being more than fair to the DeLong camp and overly hard on yourself but when your in the minority position you unfortunately have to behave that way lest you are never listened too when you know you’re right and are screaming from the rooftops. Such is the world we live in…

I have to judge this one for Cochrane in any case- his points about the causality are reasonable even if they can’t ever be proven. Seriously, all he really is doing with the WSJ article is pointing out the potential gain available on just moving closer out to the frontier. And I don’t really read that first graph, and Cochrane in the essay, as saying making those changes today raises GDP/capita immediately to those levels indicated- a point on which a number of critics in the comments seem to unfairly savage him. The US didn’t reach it’s present level of GDP without a past of good institutions that runs 200 years+ long, and I don’t think Cochrane would argue that changes made today wouldn’t require a number of years/generations to allow the increased growth to produce the GDP/capita income on that graph. Really, is DeLong ready to argue improvement can’t be made? If you think out-of-sample matters, why not voice support for producing an in-sample data point?

Would stronger property rights protections be considered in this model an increase or decrease in “regulations”?

The World Bank’s Doing Business Index is premised on a right-libertarian view where greater property rights protection is viewed as less government regulation, not more. However, Matt Bruenig frequently writes evaluations of government policies from a left-libertarian perspective where enforcement of property rights are viewed as a government regulation. Specifically, he compares policies relative to what would happen in a “Grab What You Can World”, a term coined by Roderick Long for a system where people only have a property right to their own bodies, not to land or other objects. In this system violence is only justified when you’ve violated someone else’s body, in contrast to a Rothbardian anarcho-capitalist society where if you homestead a piece of land you can use violence against those who trespass on it.

I wonder what countries would rank best in a freedom index constructed according to left-libertarian principles like that. I’m not sure if there are any societies that simultaneously have weak enforcement of property rights and yet strong enforcement of laws against violent crime.

Of course, a society that scored maximally on such an index would not just have weak enforcement of property right, it would severely crack down on those who use violence to defend their property claims. But I’m quite sure there are no large-scale societies, perhaps in the history of the world, that have done that. Left-libertarianism in that sense is far more of an untried system than right-libertarianism.

If we do not arbitrarily exclude states from those who can “crack down” on property rights defenses, then you can include North Korea as just such an example where violence is used against those who try to defend their property rights. Indeed a death sentence is the punishment for capitalist activity

Also Cuba, China up until recently, Cambodia 1970s, these ads all examples of death penalty against capitalist activity.

Also, I find it interesting how you use the phrases “crack down” and “trespassing” as juxtaposed against “violence” when describing state activity and leftwing permitted actions, versus private activity and right wing permitted activities.

The violent activity that is “cracking down” is not called violence, whereas defending property against invaders is called violence.

Trespassing is not called violence, whereas defending against trespassing is called violence.

It is almost as if you would consider stealing someone’s food to the point they starve to death, to be non-violent, whereas the person defending against that theft, is being violent.

More generally, it is as if you consider wealth to be somehow owned by nobody, and everybody, such that any individual who prevents others from taking the wealth by force, i.e. keeping the wealth away from “society”, are the violent people, while the thieves are peaceful all along. The 32 million people who died from privation in the Ukraine under Stalin were not victims of violence, but would have been violent if they defended their production from the theft of the armed Communists who took it all from them.

Frankly I never understood how any rational person can believe wealth is by default owned by “society”.

If however we define violence as nonconsensual activity against an individual’s person AND their (homesteaded/traded) property, then the trespassers would be the violent people and those who defend against it are not. It is rather absurd to believe or assume that the only rightful meaning of violence is physical force against your body only. Humans depend on the material world in order to live and be happy. You can kill people by taking their wealth from them. Causing someone to die in such ways is in the same class as shooting them. If the latter is violent, so is the former.

Anyway, small digression, thanks for explaining the index.

“If we do not arbitrarily exclude states from those who can “crack down” on property rights defenses, then you can include North Korea as just such an example where violence is used against those who try to defend their property rights. Indeed a death sentence is the punishment for capitalist activity.”. Well yeah, communist countries would come the closest. But they generally have lots of laws against nonviolent offenses, so they wouldn’t be optimal from a left-libertarian standpoint either.

“The 32 million people who died from privation in the Ukraine under Stalin were not victims of violence, but would have been violent if they defended their production from the theft of the armed Communists who took it all from them.” Well, if the Communists used a threat of physical force to stop people from continue to use “their” own resources, that would be a violate the principles of the “Grab What You Can World”. If, on the other hands, the Communists simply peaceably removed those resources that would be allowed.

“Humans depend on the material world in order to live and be happy. You can kill people by taking their wealth from them. Causing someone to die in such ways is in the same class as shooting them.” Well, by that argument couldn’t you equally well say causing someone to die by homesteading all the land and resources around a person, so that they have no place to acquire food, is in the same class as shooting them?

“In this system violence is only justified when you’ve violated someone else’s body, in contrast to a Rothbardian anarcho-capitalist society where if you homestead a piece of land you can use violence against those who trespass on it.”

For what it’s worth, trespassing *is* a violation of people’s bodies in those cases where one’s body was used in the homesteading (or acquisition through trade) of property.

Effectively, the trespasser has forced the owner to labor for the trespasser agsint the owner’s will.

Like if someone grew some food for himself, and someone else stole and ate it. Effectively, the thief forced the grower to grow food for him.

guest, you keep making this point, but I don’t see how it’s valid at all. If John sees a piece of land and announces that in one year from now he’s going to harvest all the crops he finds there, and Bill knowing John’s intentions decides to homestead the land and grow a bunch of crops there, how in the world is John coercing Bill into working for him? Whether Bill chooses to work on the land or not is entirely up to him; it’s not like John is going to beat Bill up if he chooses not to work on the land. So there is absolutely no connection to slavery here.

“If John … announces that in one year from now he’s going to harvest all the crops he finds there, and Bill knowing John’s intentions decides to homestead the land …”

So, in your scenario, Bill grows crops *because* he wants John to harvest ant take them.

Why would that be against Bill’s will, as per my argument?

The point is that if someone uses what you worked for *against* your wishes, he has made you his slave.

No, I’m envisioning a scenario where Bill does not want John to harvest and take his crops. I’m saying that in my example, Bill would have no grounds to object to John harvesting crops from the land against his willon the basis of it being slavery. That’s because Bill could have simply chosen not to work on the land; that wouldn’t lead to John beating him up or anything. Any work he did on the land was entirely voluntary. So there’s absolutely no connection to slavery.

” Any work he did on the land was entirely voluntary.”

Ok, but in your scenario as I now understand it, Bill owns the land, and now when John enters it, he’s a tresspasser even if both Bill and John knew John had planned to enter previously unowned land to harvest what may or may not have been there.

And John doesn’t need to physically assault Bill to violate Bill’s property rights in his body: By comandeering the fruits of Bill’s labor, John has effectively forced Bill to labor for him.

It’s functionally equivalent to threatening Bill to grow a portion of his crops for John.

In both cases, Bill grows the same number of crops, John harvests and eats the same number of crops, and both cases are against Bill’s will.

The only difference is, in one of the scenarios, Bill doesn’t know that John is going to harvest and eat Bill’s crops against his will.

“And John doesn’t need to physically assault Bill to violate Bill’s property rights in his body: By comandeering the fruits of Bill’s labor, John has effectively forced Bill to labor for him.” That’s what I’m disputing: John consuming the fruits of Bill’s labor is something that’s entirely preventable by Bill, by simply not choosing to work on the land in the first place. So it does not make any sense at all to say that John is “coercing” Bill to work.

By the way guest, how do you feel about intellectual property? I assume you don’t support it, but I think one could easily use your “slavery” logic to justify intellectual property. After all, if one person spends years developing a formula for a new drug, and then another person uses the formula and makes a bunch of pills with it, the second person is effectively making the first person work for him.

“That’s what I’m disputing: John consuming the fruits of Bill’s labor is something that’s entirely preventable by Bill, by simply not choosing to work on the land in the first place.”

But working on the land *is* Bill’s wish, which means your “solution” doesn’t bear on the argument.

I could change the scenario so that John steals something else that Bill labored to create, but that would simply be restating the argument in a different way. What would be the point in that?

Find a solution that fits the parameters of my argument, otherwise your responses are straw men.

“But working on the land *is* Bill’s wish, which means your “solution” doesn’t bear on the argument.” Well, Bill could have all kinds of wishes. The fact that John’s behavior doesn’t satisfy all of Bill’s desires isn’t John’s fault. The point is, work is only coerced if there is no choice not to do it. Since Bill has every choice not to do the work, it is not the case at John is coercing him.

Put another way, in the “Grab What You Can World” we’re discussing: Bill, has two choices: he can choose to work on the land, and risk John taking the crops that result, or he can choose to not work on the land, and eliminate all possibility that John will consume any fruits of his labor. Choosing the first option rather than the second is entirely up to him, so there is no coercion involved here.

“The fact that John’s behavior doesn’t satisfy all of Bill’s desires isn’t John’s fault.”

All of Bill’s desires aren’t the issue, and I’m calling “troll” on this, now, since I’m convinced you know this.

Bill’s desires for that which he labored to create *is* the point, for everyone else’s benefit.

“… he can choose to work on the land, and risk John taking the crops that result …”

Bill could homestead, and grow food on, the land with knowledge of a 100% chance of possibility that John will enter the land, harvest and eat the crops, and that would still be coersion.

Because Bill’s intent is to do something other than allow John to harvest and/or eat them.

Bill owns the land and doesn’t want John to have the crops he grows, therefore John’s harvesting and eating of Bill’s crops is a violation of John’s property rights in his body.

Aside: I noticed another straw man on your part:

“So it does not make any sense at all to say that John is “coercing” Bill to work.”

Never said that.

😀

Bill voluntarily grew the crops. I never said otherwise.

John comandeered Bill’s labor when he took Bill’s crops without his permission.

“Bill could homestead, and grow food on, the land with knowledge of a 100% chance of possibility that John will enter the land, harvest and eat the crops, and that would still be coersion.”

*Facepalm*

😀

I chalk this up to unwittingly granting you the premise, *after the fact*, of the utility of the word “coerce”.

Which only happened after you used it.

I’ll modify this misnomer by saying that a 100% chance of John entering Bill’s land and taking his crops would still be a violation of Bill’s property rights in his person.

“Bill’s desires for that which he labored to create *is* the point, for everyone else’s benefit.” The point I was making is I don’t see what the moral difference s between John not satisfying Bill’s desire for what Bill labored to create and John not satisfying Bill’s other desires.

“Bill voluntarily grew the crops. I never said otherwise.

John comandeered Bill’s labor when he took Bill’s crops without his permission.” Well, I don’t think “commandeering someone’s labor” is a meaningful expression. Labor is an action, not a thing. Now if you just want to axiomatically assert that it’s wrong to take the fruits of someone’s past labor, I suppose I can’t stop you. But I just don’t think that it makes sense to classify taking the fruits of someone’s past labor as “slavery” or as a violation of the person’s right to their own body.

“I’ll modify this misnomer by saying that a 100% chance of John entering Bill’s land and taking his crops would still be a violation of Bill’s property rights in his person.” We’ll, perhaps we can resolve this by clarifying some terminology. Tell me this: what do you think it means to say “Person A has a property right in object X”? I would define it as “It is justified to use violence against people who physically touch or assault object X without the consent of person A.” Do you agree with that definition? If you do, then I don’t see how you can possibly believe that trespassing on land that someone has done work on violates a person’s property right in their body.

“The point I was making is I don’t see what the moral difference s between John not satisfying Bill’s desire for what Bill labored to create and John not satisfying Bill’s other desires.”

Again, with the trolling: You know we don’t believe in positive rights.

Bill has a negative right not to have his property rights in his person violated.

Your response is, again, a straw man.

For everyone else’s benefit, I never said John was violating Bill’s rights by not satisfying Bill’s desires.

That was never said, and Keshav knows this.

“… I don’t see how you can possibly believe that trespassing on land that someone has done work on violates a person’s property right in their body.”

For the same reason that slavery violates a person’t property right in their body.

What, then? In your view, a slave’s property right in his body isn’t being violated unless the slave master physically touches him?

I guess regaining property rights, in your view, is as simple as doing what you’re told.

“What, then? In your view, a slave’s property right in his body isn’t being violated unless the slave master physically touches him?

I guess regaining property rights, in your view, is as simple as doing what you’re told.” Well, if the master neither physically touches him nor threatens to physically touch him, then yes he does not violate the slave’s property right in his own body. (Of course, I would not actually call such people a slave and a master.)

“Again, with the trolling: You know we don’t believe in positive rights.” guest, I assure you that I’m not “trolling” or knowingly stating falsehoods about your positions. I didn’t think you were in favor of positive rights, I was just trying to argue that the sorts of arguments you’re making could be used to justify positive rights.

“Well, if the master neither physically touches him nor threatens to physically touch him, then yes he does not violate the slave’s property right in his own body. (Of course, I would not actually call such people a slave and a master.)”

Nice try.

Again, for everyone *else’s* benefit, merely “threatening” to physically touch someone is not actually physically touching someone.

It’s the very reason why “touch” was qualified with the word “physically” – to eliminate non-physical violations of property rights from the thought experiment at hand.

I trust it’s clear to most that Keshav is simply playing games.

He is fond of these Devil’s Advocate games, not to advance the discussion, but to simply be contrarian.

I have voiced this displeasure concerning Keshav in the past, so this is not a new frustration, nor one borne from a tantrum, an off day, nor a monentary lack of tact.

Keshav *is* trolling – which can be entertaining for me – but not right now.

Maybe later.

😀

“It’s the very reason why “touch” was qualified with the word “physically” – to eliminate non-physical violations of property rights from the thought experiment at hand.” OK, if that was the purpose of your thought experiment, then I concede that point; I did not state my definition of property rights properly. Let me restate it now: “Person A has a property right in object X” means “It is justified to use or threaten to use violence against people who physically touch or threaten to physically touch object X without the consent of person A.” Assuming to agree with this revised definition, I still don’t see how you can possibly believe that using land that someone else has worked on is a violation of their property rights in body.

“I have voiced this displeasure concerning Keshav in the past, so this is not a new frustration, nor one borne from a tantrum, an off day, nor a monentary lack of tact.” guest, I’m sorry you have such a negative view of me, but I assure you that it’s not justified. You can accuse me of many things, but intellectual dishonesty is not one of them. Whether on the Internet or in real life, dishonesty is simply not one of my flaws (which is not to say that I don’t have other flaws). I truly and sincerely believe that there are no compelling arguments to justify a right-libertarian system over a left-libertarian system, and I’m having this discussion to see whether I am wrong about this. I should say, in case you don’t already know it, that I am neither a left-libertarian nor a right-libertarian, rather I believe that government should have a bigger role and there should be laws against many non-violent crimes. But I’m interested in the left-libertarianism vs. right-libertarianism issue, both because I’ve been reading Bob’s blog for years and because I’ve reading Matt Bruenig’s left-libertarian critiques of right-libertarianism.

By the way, guest, is this slavery argument something you came up with, or are there other other libertarian thinkers who justify property rights in the same way? Because the usual justifications I’ve seen of property rights are Hoppe’s argumentation ethics, Rothbard’s trichotomy argument, Ayn Rand’s just deserts argument, and other people just taking the Rothbardian non-aggression principle as an axiom.

AD and Bryan:

The reason I’m apologizing is that it was an unforced error on my part, and that I added to the confusion. I wasn’t wrong for trying to shock you guys with the move DeLong pulled by switching graphs and saying it was what Cochrane drew (which is not just misleading, it is a false statement). Rather, I was wrong in how I interpreted what was going on with the computer code, and that kind of took the wind out of my zingers.

Bob, I certainly agree that Delong should have said “Cochrane draws a graph which is mathematically equivalent to this graph” rather than “Cochrane draws this graph”. But that seems to me to be a relatively minor misstatement.

By the way, I think Cochrane is wrong in his response when he says that Delong is criticizing him for using a log plot. I don’t think Delong has any problems with Cochrane using a log plot.

Bob, Noah Smith’s blog post has a good explanation of what Delong was doing: noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2016/05/brad-delong-pulpifies-cochrane-graph.html

“Cochrane’s conclusion disappears entirely! As soon as you add even a little curvature to the function, the data tell us that the U.S. is actually at or very near the optimal policy frontier. DeLong also posts his R code in case you want to play with it yourself. This is a dramatic pulpification of a type rarely seen these days.”

In other words, Delong is showing that if you give the math even the slightest opportunity to do so, it will tell you that significantly more deregulation will actually hurt, not help, US economic growth. (Using a linear fit won’t tell you that, since it’s mathematically impossible for a line to go down once it starts going up, but even introducing a small amount of linearity will easily give you that conclusion.)

even introducing a small amount of NON-linearity*

Hmmm, Brad’s quadratic curve fit against the log incomes actually gives larger benefits for a more “Business Friendly” environment, so choose which nonlinearity you prefer. *SHRUG*

From Noah’s post (right under the curve fit graph)

This is basically wrong, bordering on dishonest. The row of orange dots (quadratic) kicks UP on the right hand side and continues upward if you care to extend that bottom axis out to 100. The rows of blue (4th order) and red (cubic) dots roll over the crest and kick DOWN on the right hand side. The black dots (linear) are not shown, but they do come up if you run Brad’s code, and those run fairly close to the orange dots.

Thus, Noah either doesn’t understand what he is looking at, or just feels like spinning the story a bit. Anyway, some nonlinearities will fall in Cochrane’s favour (and it’s visible on the graph too).

I might also point out, there’s always danger in extrapolation into unknown territory… but if I was going to have a go at doing it, I would avoid high order polynomials.

re: “I might also point out, there’s always danger in extrapolation into unknown territory… but if I was going to have a go at doing it, I would avoid high order polynomials.”

This sounds noble but is less noble when we recall we’re already in log points and so we’re already embracing the prospects of explosion during extrapolation.

I think the issue is that a quadratic fit is still too restrictive: as long as the graph is increasing and concave up somewhere, it has to stay that way everywhere. But that doesn’t allow for the possibility that the graph is increasing and concave up when you’re dealing with a heavily regulated economy, but that’s no longer the case once you go as far right as the United States.

Let me put this a different way guys, if you stand back and look at the cloud of sample points you see a fairly spread out group with a distinct general trend that looks roughly linear.

So now you fit from first order up to fourth order polynomials and find that in the body of the sample group all of those fit about the same. There really isn’t a whole lot of air between them in the areas most heavily covered by sample points. Therefore in terms of getting a better fit to the data, the high order polynomials just aren’t delivering much, so how do you justify using them?

I’d still go for the lower order fit, given that adding three extra degrees of freedom didn’t buy you anything in this case.

#5) Always use your R-code… especially when it’s downloadable

I got the same impression at first glance, which was why I was curious as to what Brad had attempted. I was a bit surprised to find that Brad’s numbers actually gave answers very similar to what Cochrane was saying. Thus, from a mathematical perspective there wasn’t much difference between them.

The only dispute is whether it is reasonable to presume an exponential extrapolation under the circumstances. IMHO Brad didn’t do a good job of explaining what his point was.

#6) If you have a problem with someone, at least make a fair effort to convey what you on about.

We would have also accepted:

#5) No need to look stupid, as per #1; Just act like you don’t need to explain yourself, saying, “When I learn the facts, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

*Takes a bow*

1. Do unfollow Noah Smith.

2. Do follow John Cochrane.

3. Do not follow Brad DeLong.

“We’re going to build this echo-chamber and we’re going to make the Keynesians pay for it!”

(Walter Block you have my permission to use that if you want to)

My favorite Daniel Kuehn line of all time.

Noah Smith is essentially a 12 year old YouTube commenter. Why anyone would follow him I have no idea. DeLong has a similar infantile style, but occasionally has something interesting to say.

“They’re bringing charts. They’re bringing math. They’re inflationists. And some, I assume, are good people!”

E. Harding is an Inflationist, as is Trump.

This was actually a really good burn. Bravissimo.

That was pretty good E. Harding.

Cochrane explains why DeLong is so horrifically wrong: http://johnhcochrane.blogspot.com/2016/05/delong-and-logarithms.html

As Cochrane points out 1) DeLong is a very ungracious debater, 2) Cochrane was *illustrating* a phenomenon that has been the subject of virtually countless pages of high-quality research.

So, game, set, match: Cochrane.

Also, Noah Smith is a clown.

Well, I won’t contest the claim that Delong is impolite, but this is a case of righteous indignation, not just arbitrary outrage for no reason. And Cochrane is wrong in claiming that Delong has a problem with Cochrane’s decision to use a log plot. That’s not the issue at all.

Perhaps, but his broader point stands: the chart was an illustration based on the findings of much more sophisticated work on the subject. You can believe that there isn’t an important causal effect of regulation on growth, but the literature doesn’t bear out that position.

Out of sample extrapolations like DeLong’s remain as idiotic as they were before this Cochrane v DeLong argument started.

Well, Cochrane and Delong are both doing the same kind of out-of-sample extrapolations in their graphs. Delong is just saying that a linear fit is a bad choice, because it doesn’t allow for any possibility of showing that the U.S. Is already at peak business friendliness.

“in their graphs”

But there’s a difference between what Cochrane calls the “local derivative” and out of sample extrapolation. Did Cochrane actually say “Look, we can have infinite wealth!!!” or did he say “The local derivative is high?” He actually said the second one. So, again, this is an example of leftist straw man on the part of Delong.

This point would be more convincing if you worked on the Corpus Christi campus.

LOL! Nice, Craw.

Actually I just accepted a position with the University of Georgia (yes, in Athens), which I think is going to be a great fit for me.

Cochrane updated his blog with a fairly reasonable answer to the extrapolation danger.

How “seemingly obvious” this is might be arguable, but he does have a point that in limited space you don’t want to spend all your efforts apologizing for drawing a straight line.

Bob, have you seen Delong’s follow-up, where he makes slides out of his critique of Cochrane?

Sorry, I forgot to put the link: http://www.bradford-delong.com/2016-05-06-cochrane-slides.html

Wow, the more I read this blog and the further responses to it, I am starting to realize how important Mises’ words about historical data are. Interesting stuff. I think Dr Murphy could have summed up the whole debate with one line, even without having to reference Mises’ words about historical data:

“Joke’s on you guys.”

Furthermore, it seems that even Financiers who believe in the abstract models they build, get carried away not understanding the limits of math theory. Math must be understood as a form of estimating, or a numerical description of what exists. In essence, it is philosophy with numbers. Many people believe math, perhaps for it’s complexity, arrives at absolutes.

>Never be really smug, because in case you make an innocent mistake you end up looking like an idiot.

You realize these are economists, right? You’d have better luck convincing house cats of the benefits of veganism.

FWIW, dogs will eat fruit – for those who might have wondered how there could have been no death before the Fall.

*Takes a bow*

To change directions, am I the only one who finds Smith’s gravatar somewhere between hilarious and nauseating? Like if Donald Trump picked Hayek as his gravatar?

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/hayeks-case-against-unlimited-immigration/

You would be surprised what’s out there… 🙂

Oh I can top that. Here’s Rothbard basically agreeing with the book “The Camp of The Saints”:

“I began to rethink my views on immigration when, as the Soviet Union collapsed, it became clear that ethnic Russians had been encouraged to flood into Estonia and Latvia in order to destroy the cultures and languages of these peoples. Previously, it had been easy to dismiss as unrealistic Jean Raspail’s anti-immigration novel The Camp of the Saints, in which virtually the entire population of India decides to move, in small boats, into France, and the French, infected by liberal ideology, cannot summon the will to prevent economic and cultural national destruction. As cultural and welfare-state problems have intensified, it became impossible to dismiss Raspail’s concerns any longer.” – Nations by Consent: Decomposing the Nation-State Murray Rothbard

Lest I be accused of being deliberately misleading, Rothbard of course points out that, in his first best ideal of a totally privatized nation, the people thereof may exclude immigrants from their private property. As Bob might say “Privatize the Borders!”

My own position continues to be that there is no reason for any state that is not a democracy to restrict immigration, but that as long as one insists on democracy, there is no other choice.

In my opinion, culture exists prior to and beyond the state. Individuals have a culture, although it only manifests when those individuals come together in groups… and that is to say it always manifests, because humans achieve a lot more when working in groups than they can do individually.

Basic concepts such as property rights (and not just the arm waving abstract property rights in general, but specific understanding of your property and my property) need to reside in the individuals willingly if those concepts are going to work at all. The police cannot be everywhere all at once, so any sort of society depends on most of the people to play by the rules most of the time.

Now the state will co-opt culture and claim to own it, and to some extent will use police to reinforce cultural norms thus becoming “protector” of the culture. This is fine as far as it goes but the state encourages a confusion that the state bestows culture on people… no it’s the other way around people bestow culture on the state. If you import enough different culture into a state, then the nature of that state will change, and this means the nature of property rights will also change, and all of the things that go with that, including our shared expression of liberty.

If you have one culture that believes that women are property, and another culture that believes women are free willed individuals capable of themselves owning property… then these two cultures are not compatible. There are two possible outcomes: either one must give way to the other, or the two must remain segregated. In between these two possibilities is only war.