Calling Noah Smith’s Bluff on Demand- Versus Supply-Side Recessions

I still intend to give a more thorough response to Karl Smith and Daniel Kuehn in light of their reactions to my “gnome” article. One of their main themes is to be shocked, shocked that we Austrians keep accusing the Keynesians of thinking in aggregate terms. Why, Karl’s middle name is “microdata,” and Daniel argues that Keynesianism is dependent on worrying about capital structure.

So in lieu of answering them head-on, let me pick a good example of what I have in mind. There are plenty of prominent Keynesians who do precisely what we Austrians are talking about–we’re not inventing a strawman here. I could pluck tons of examples from Krugman, but I’m sick of him right now. So let’s pick the rising star Noah Smith:

Does output falter because people don’t want to buy as much stuff, or because we become unable to make as much stuff as we used to? This is a debate that has gripped the macroeconomics profession for many decades. Which is kind of surprising to me, because it is so obvious that demand shocks are the culprit.

The reason is prices. If recessions are caused by negative supply shocks, then we should see falling output accompanied by rising prices (inflation). If recessions are caused by negative demand shocks, we should see falling output accompanied by falling prices (disinflation or deflation).

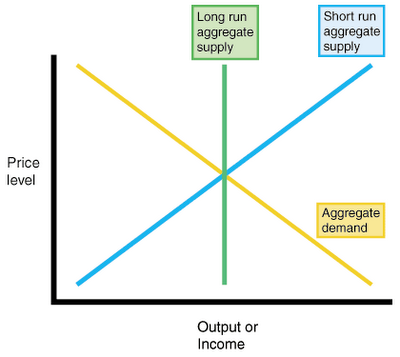

Draw a supply-demand curve for the whole economy, and it looks like this:

A negative shock to supply – for example, a resource shortage or an increase in harmful government regulation or a “negative technology shock” – will shift either the long-run aggregate supply curve or the short-run aggregate supply curve (or both) to the left. The new equilibrium will have lower output and higher prices. However, a negative shock to demand – for example, an increase in the demand for money – will shift the aggregate demand curve to the left; the new equilibrium will have lower output and lower prices.

In all of the recent recessions, faltering output has been accompanied by lower, or even negative, inflation. This means that demand shocks must have been the culprit. If “uncertainty about government policy” were really the cause of the recession, as many conservatives claim, then we would have seen prices rise – as companies grew less willing to make the stuff that people wanted, stuff would become more scarce, and people would bid up the prices (dipping into their savings to do so). I.e, we would have seen inflation. But we didn’t see inflation.

So it seems that the stories that conservatives tell about the recession – “policy uncertainty,” “recalculation,” or even a “negative shock to financial technology” – are not true. The stories that everyone else tells about the recession – “a flight to quality,” “increased demand for safe assets,” etc. – look much more like what basic introductory macroeconomics would predict.

…

The basic point here is about the dangers of doing what Larry Summers calls “price-free analysis”. If you ignore prices, it is possible to convince yourself that recessions are caused by technology getting worse, or by people taking a spontaneous vacation, or by Barack Obama being a scary socialist. If you pay attention to prices – as all economists should – it becomes harder to believe in these things.So the question is: Do conservative-leaning economists push these stories because they believe that we live in a world that is vastly more complicated than anything that can be described in Econ 102? Or is it just because they choose to ignore Econ 102 completely?

OK, so no matter what, I hope Karl and Daniel will now cut us Austrians some slack. Noah isn’t talking about production possibilities frontiers, about micro-level data on the marginal efficiency of capital, about sectoral adjustments, blah blah blah. He is using a graph from Econ 102 and suggesting that “conservatives” who blame supply-side factors are either stupid or liars. (I wonder where he got that trait from?)

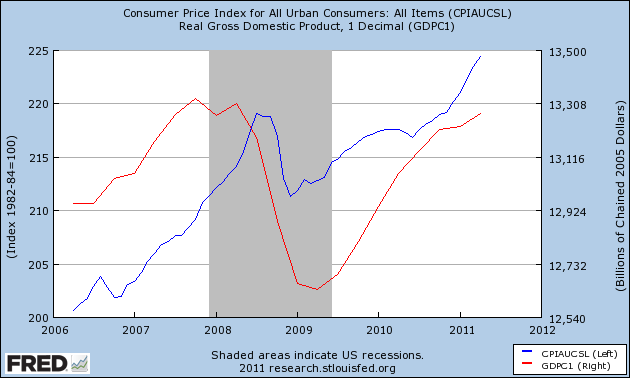

Moving on, sure Noah, I’ll call your bluff. Let’s look at what happened to real output and prices since 2008:

OK, the latest data show that since early 2008, prices are now higher and real GDP is lower. So according to that simple graph Noah gave us above, the inescapable conclusion is that we’ve had a supply-side shock. Does Noah think things are more complicated than that graph, or is he choosing to ignore Econ 102 completely?

Now let’s be less facetious and smug. In the beginning, Noah’s story would have worked. Prices were falling along with real output. Yet that was part of my gnome story–in a world where real output is crashing because of structural factors, people might freak out and demand higher cash balances. (If you woke up tomorrow 300 miles from your house, and all businesses were closed because their equipment was missing, would you feel like spending $4 on a coffee like you normally do?)

So using that Econ 102 graph, what happens if supply and demand shift left? In that case, real output falls a lot more than prices. And lo and behold, that’s what the real data really look like–real output fell more (in percentage terms) than CPI did.

Finally, let me be fair to Noah. In his verbal exposition (as opposed to his simple graph that he hoped the Nobel laureates at Chicago would understand), Noah acknowledges that a demand-side story might result not in literal (price) deflation, but rather in disinflation.

But hold the phone. Now things are getting really subtle, and there’s no way I would ask this of an Econ 102 class (except maybe on a bonus question on an exam). The way you model this kind of thing, is that you say over time, the Aggregate Supply curve shifts left, because producers expect general price inflation. Thus, to induce producers to be willing to supply a given quantity, over time the market price has to go up. (That’s what it means for the AS curve to shift left over time.)

So in this context, the Fed needs to keep the AD curve moving to the right consistently, in order to keep real output constant. Because AS shifts left and AD shifts right, prices obviously go up. Finally, if for some reason the Fed falls down on the job, and AD doesn’t shift as much as people thought, then you’d see real output drop while prices would raise at a slower rate than before.

THIS is really what Noah has in mind. But it’s interesting that this is actually a story about Aggregate Supply, and it depends crucially on expectations. That doesn’t make it wrong, but it sure as heck means that things are a lot more complicated than, “People aren’t spending enough, prices are falling, this is a demand shock, you conservatives are idiots.”

Leveraging the EFSF Bailout Fund would Leave European Taxpayers More Vulnerable

This is such an obvious point, but I still haven’t seen anybody spell it out. So the context is the stabilization fund that the European powers are setting up to bail out the PIIGS:

As Europe continues to battle its debt crisis, Timothy Geithner has a suggestion. The Treasury secretary today called on euro zone officials to leverage the region’s roughly $600 billion bailout fund, an insider tells Reuters. Geithner didn’t provide details on how Europe should go about the move, nor did he point to the US TALF fund, created in 2008 to back lenders; some have suggested TALF could be a model for Europe’s bailout fund. Geithner conceded, however, that the US is “not in a particularly strong position to provide advice to all of you,” notes AP. “We still have our challenges in the United States,” he said, and “our politics are terrible… maybe worse than they are in many parts of Europe.”

Leveraging the fund would be a “radical” move, writes Jan Strupczewski, but it could be a way around some leaders’ opposition to expanding the fund itself.

Since I was just over in Europe, there was lots of buzz about this stuff. The above excerpt it typical of the coverage. The original size of the fund was 440 bn euros, but then in recent meetings ideas were floating to make it effectively up to 2 trillion euros. The German finance minister (I think?) clarified that they weren’t talking about kicking in more money, but rather they were going to guarantee up to 20% of the losses on PIIGS bonds, rather than buying the bonds outright. Thus, for the same 440bn euro fund, they could get five times the leverage.

What a great idea! Of course, the downside is, if those PIIGS bonds drop in value, then the EFSF will suffer five times as many losses.

Consider the scenario where the PIIGS bonds drop 20% in market value after the EFSF intervenes. Had the fund just bought 440bn euros-worth of the bonds in the first place, then the European taxpayers would be out 20% = 88bn euros.

But if, instead of buying PIIGS bonds outright, the fund guarantees the first 20% of 2.2tn euros of bonds, then if those bonds drop 20% then the European taxpayers are out the full 440bn euros.

Like I said, this is an incredibly obvious point, but after reading at least half a dozen articles on this, nobody has mentioned it. Everyone is acting like this is a neat way to provide more “help” for the same taxpayer liability.

Is Spending Money a Market Failure?

Steve Landsburg is trying to think through the implications of assuming sticky prices. But it’s the first part of his post that strikes me as fishy:

[L]et me start with something I do understand — a world with flexible prices and (for simplicity) no inflation. (What follows is standard textbook material, which we all learned from Milton Friedman, who in turn probably learned it from Iriving Fisher. It is not controversial. If you think it’s wrong, the probability is 99.9999% that you’re mistaken.)

Let’s consider the supply and demand for money in this economy. Money is supplied at (essentially) zero social cost (the cost of paper and ink being essentially zero). However, the private cost of holding money — measured in forgone consumption — is positive. Whenever the private cost of an activity is greater than the social cost, people engage in too little of that activity. In this case, they hold too little money. Or in other words, they spend too much money. That means that each additional dollar you spend must hurt your neighbors more than it helps them. It remains to ask who, exactly, is hurt by your spending.

Answer: When you spend a dollar, you bid up prices. That’s good for sellers, bad for buyers, and bad for other people holding money (because it depletes the value of their dollars). The first two effects wash out, because every transaction involves both a seller and a buyer, leaving the moneyholders as the bearers of the net harm.

Note the logic: First we identify a discrepancy between private and social cost. This tells us that spending a dollar must (at the margin) do more external harm than good (”external” means “not felt by the decisionmaker”, the decisionmaker in this case being the spender). This in turn tells us that we ought to ask who bears that harm. The answer isn’t immediately obvious, but it’s clear once it’s pointed out.

I’ve often thought that I’m one-in-a-million, so I take up Steve’s gauntlet while acknowledging the intrepidity of assaulting Irving Fisher. (Then again, he was wrong on Prohibition and the 1929 stock market.)

At first I tried to apply Steve’s logic to coat-check tickets. (In other words, would Steve say that the private cost of holding–rather than cashing in–a ticket to get your coat back, is higher than the social cost?) It wasn’t clear how to make the analogy work, since the issuer of the tickets can’t just print them up at zero cost; they are supposed to be backed by a coat.

So this led me to think about commodity money. Would Friedman’s analysis apply to an economy with gold as the money? (If so, note that in a Walrasian model you can pick any good as the numeraire.) I guess not, since a major difference is that you have to mine the gold.

OK so it’s clear that for this analysis to “work,” we have to be talking about fiat money. But then that led me to a new objection. For the sake of brevity, let me just ask: Steve, what’s to stop me from writing the following?

Let’s consider the supply and demand for money in this economy. Additional money is supplied that confers (essentially) zero social benefits (since having more pieces of paper in circulation doesn’t make the community actually wealthier). However, the private benefit of holding money — measured in liquidity services — is positive. Whenever the private benefit of an activity is greater than the social benefit, people engage in too much of that activity. In this case, they hold too much money. Or in other words, they spend too little money. That means that each additional dollar you spend must help your neighbors more than it hurts them. It remains to ask who, exactly, is helped by your spending.

Answer: When you spend a dollar, you bid up prices. That’s good for sellers, bad for buyers, and good for other people holding goods and services (because it increases the market value of their goods and services). The first two effects wash out, because every transaction involves both a seller and a buyer, leaving the goods-holders as the bearers of the net benefit.

Note the logic: First we identify a discrepancy between private and social benefit. This tells us that spending a dollar must (at the margin) do more external good than harm (”external” means “not felt by the decisionmaker”, the decisionmaker in this case being the seller). This in turn tells us that we ought to ask who bears that benefit. The answer isn’t immediately obvious, but it’s clear once it’s pointed out.

If Steve doesn’t like that angle, let’s riff on Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis, applied to cash balances:

OK let’s stipulate for the sake of argument that when people spend money, they are imposing negative externalities on people. But by the same token, when people acquire money, they must be imposing positive externalities on people. Since no one (outside of Bernanke) is a counterfeiter, these effects cancel out over the course of each person’s lifetime, properly adjusting for interest rates, passing on property to heirs, etc.

Last point: I am not bothering to look up Friedman’s classic essay on this issue. I am fully prepared to admit that I am wrong, within the context of a standard neoclassical model. But Steve’s post isn’t making me “see” it…

I Hope Scott Sumner Is Happy

Over on his blog, Scott Sumner has been saying “I hope the inflation hawks are happy, this is what tight money looks like” after the big sell-off in the markets when “Operation Twist” turned out to be sterilized. That’s a bit like pointing out the heroin addict going through terrible withdrawal pains and saying to his mom (who checked him into rehab), “I sure hope you’re happy now. That’s what cold turkey looks like.”

Anyway, Bob Roddis sends me this recent post from our good friend Matt Yglesias. I hope Scott Sumner is happy; this is what it looks like when you preach for 3 years that printing money leads to costless prosperity:

There’s no particular reason why monetary policy has to be conducted through interactions between the central bank and a banking system. Or, rather, the reason it’s done this way is historical. Under an older set of institutional arrangements, a central bank was actually a bank and it’s importance derived from its interaction with other banks. But in the modern day, you could do something completely different. For example, Peter Frase notes that from time to time, proposals pop up for a national basic income. You could, for example, have the government send a check for $600 each month to every American citizen. Alternatively, you could have the central bank send a check for approximately $600 in newly printed money each month to every American citizen and vary the exact amount of the check in order to stabilize demand. Or, of course, you could use different numbers.

I’m not sure the politics of trying to do things that way would really work out well in the end, but it’s a potential idea for your humanitarian utopia of tomorrow.

Lawrence O’Donnell Surprisingly Bold on the NYPD

Who cares why he did it…LOD is surprisingly bold here:

My Favorite Newscaster in Slovakia

If someone can figure out how to embed this video, that would be cool.

Short Clip on Solyndra

I’d like to say I had a lot of input into this video, but alas my colleagues at IER did it all on their own. I had suggested that I take my shirt off and do an impression of Joe Biden while standing in the bathroom. But they thought it would be too esoteric for our target audience.

Recent Comments