Are Sumner and Krugman Incorrectly Claiming Victory?

A friend who is a very sharp economist mentioned to me that when he reads my critiques of Sumner, it is very challenging to discern my argument. So if he was having trouble following my posts, I pity the fool with a normal IQ.

So for this post, I will start out at Square One. It’s appropriate to do so, because my ultimate point is going to be that–from what I can tell–Scott Sumner and Paul Krugman are taking what should be a stunning refutation of their position, and somehow turning it into a glorious confirmation. I am not accusing them of lying; I actually think that we’re so hip-deep into the arguments, that up becomes down.

So like I said, let’s start simple. Sumner (and Krugman but I’ll focus on Scott since I know his position better) believes that “money matters.” In other words, changes in the supply of, and demand for, money can lead to “real” changes. For example, if all of a sudden the quantity of money fell in half, it’s not the case that instantly all prices would go down 50% as well, leaving the “real” economy undisturbed. On the contrary, there would be a huge convulsion in the market, with lots of people getting thrown out of work, and the production of physical goods and services dropping sharply.

So far, so good. And to be clear, Austrian economists agree that monetary disturbances can affect the “real” economy; that’s the essence of the Mises-Hayek theory of the business cycle.

OK, so where does the disagreement begin? When it comes to our current recession, I say that the tremendous boom under Greenspan distorted the capital structure of the economy. We had painted ourselves into a corner, as it were, and output had to fall (relative to its height at the end of the boom) while workers and resources were shuffled around into more sustainable niches. When the crisis hit, the Fed and the government should have sat back and done nothing. (Or better yet, pegged the dollar to gold, cut spending, and cut marginal tax rates–I can dream.)

I admit there would have been an awful recession–the worst since the early 1980s at least–and a lot of investment banks would have gone down. But after 6 months or so, unemployment would have peaked, and a genuine recovery would have begun. By now, the awful Depression of 2007-08 would have been a bad memory. Unfortunately, the Fed and the government didn’t do what I would have recommended. Instead, they implemented the same strategies that their predecessors deployed in the face of the dot-com crash–times ten.

Sumner’s views are very much different. He says that the housing boom did indeed necessitate some “recalculation,” but that the reason for our disastrous economy since 2008 is that Bernanke hasn’t inflated enough. Specifically, the demand to hold money went way up, and Bernanke did not offset it with a corresponding increase in the quantity of money. The result is that nominal GDP (NGDP) fell. NGDP measures how much total spending occurs, and is the flip side of how much income people earn. So in the aggregate, people were earning less income in 2008 than they would have guessed the year before.

Sumner would admit that this “monetary shock” would be no big deal, so long as wages and other prices could adjust quickly. (In that scenario, people earn less money income than they expected, but no big deal because their money expenses are lower than they expected, etc.) Unfortunately, in the real world, prices and in particular wages are “sticky downward,” meaning they can’t go down as easily as they go up.

So as far as policy conclusions, Sumner and I are in complete disagreement: I think the Fed should stop pumping in more base money, and let interest rates rise as they may. (It’s a little harder for me to say if the Fed should start selling off its assets, or just let them mature without rolling them over, etc.) Sumner, on the other hand, would buy a round at the bar if Bernanke announced that he’d buy another $1 trillion in long-term Treasuries over the next 6 months.

Now instead of the more conventional open market operations, suppose instead that Bernanke decided to implement his infamous helicopter-drop scenario. In other words, Bernanke was literally going to print up $1 trillion in new Federal Reserve Notes, and then start randomly distributing them to US citizens. What would Sumner and I predict?

I grant you there are nuances on both sides, but I think to a first approximation–if we were on Family Feud and had to summarize our positions in 10 seconds before facing off–I think we would say something like this:

MURPHY: That’s a terrible idea! The problem with the economy is real, or structural. You don’t fix that by throwing green pieces of paper at the problem. Dumping more money into the economy won’t increase physical output, it will just make nominal prices go up. Monetary inflation won’t lead to real GDP, it will just lead to price inflation.

SUMNER: Murphy should stick to making YouTubes. The problem with the economy is nominal. It’s not structural, it’s monetary. Dumping more money into the economy will increase the output of physical things. The monetary injections will boost nominal GDP all right, but it will also boost real GDP. So we won’t see prices going up, as Murphy predicts.

Like I said, I’m obviously oversimplifying. But to a first approximation, I think the above is fair. In particular, Sumner (and Krugman) have been gloating over the fact that people like me wrongly predicted large consumer price inflation (at least measured by official CPI) when Bernanke started pumping in money. To restate the important conclusion: Sumner and I both agree that pumping in a trillion new dollars would raise NGDP. But I think it would (mostly) show up as increases in P, without raising RGDP (much). Sumner in contrast thinks it would (mostly) show up as an increase in RGDP, without raising P (much).

We’re almost to the finish line. Let’s take out nominal GDP and put in stock prices. Again, to a first approximation, the people like me who think the economy is stuck because of “real” issues right now, would think that pumping in a bunch of new money could very well raise the nominal level of stocks, but it would also raise expected price inflation.

In contrast, I would have thought Sumner’s position would logically entail that monetary pumping should lead to rising stock prices with stable (price) inflation expectations. This would match Sumner’s interpretation that the monetary pumping raised the prospects for future income growth, which would be “soaked up” by an expansion of real output. So nominal incomes would rise, but prices not nearly as much.

OK so assuming my rough characterizations of the “real” vs. “monetary” camp is right, let’s go to the tape and see which side has the data on its side:

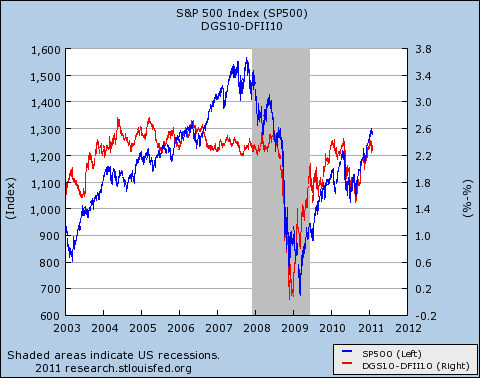

The above chart shows the movement in the S&P 500 (blue line, index on left) against a common benchmark of “inflation expectations” (red line, gap between yields on 10-year regular Treasuries and TIPS on right).

As you can clearly see, ever since the crisis set in, movements in the stock market have matched perfectly with movements in expectations about the future price level. In other words, whenever the stock market has gone up, there has been a corresponding increase in expected price inflation over the next ten years.

I would have thought, to a first approximation, this would be a stunning victory for the “real” theorists. If, contrary to the above chart, the data had shown that the huge upswing in the stock market starting with QE1 in March 2009, went hand-in-hand with stable inflation expectations, then Sumner could have said, “Well now Murphy, what’s your story? If the market is booming just because of funny-money, and not because investors expect real economic growth, then why aren’t inflation expectations moving up too?”

(Don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t have surrendered. I would have said, “Uh, it’s a bubble.”)

But I don’t have anything to be embarrassed about; the chart above is exactly what the “real” theorists would have hoped for, if they want to claim that the economy is stuck in a structural rut, and that throwing more money at it can only raise nominal figures.

PUNCHLINE: As the reader may have guessed, the reason I went through all this is that Sumner and Krugman claim that the above chart shows they’re right. Go figure.

And incidentally, one last thing: My real purpose in this post isn’t to say, “Ha ha, what fools. They don’t even know the implications of their own position.” On the contrary, my purpose is to show what a scam macroeconomics is. Sumner and Krugman no doubt can (and Sumner perhaps will, in response to me) tell a great story, with all the i’s dotted and t’s crossed, about why the above chart proves they are right.

And yet, if the chart had looked the other way–say, if the behavior of the red and blue lines during 2006-2007 was shifted forward to 2009-2010–then it seems to me, they could have just as easily told a great story, with all the i’s dotted and t’s crossed, about why that chart from an alternate universe proved that they were right.

It is gauche for me to be the first to comment on my own post? I hope not.

I was re-reading Scott’s original post to refresh my memory as to why he thinks the above chart is so conclusive. And I came across these funny portions, which I’ll juxtapose for comedic value:

[Sumner:] There is no way to overstate the importance of these these findings. The obvious explanation (and indeed the only explanation I can think of) is that low inflation was not a major problem before mid-2008, but has since become a big problem. Bernanke’s right and the hawks at the Fed are wrong.

[Guy in the comments at Sumner’s post:] I think stock prices have been rising with inflation expectations because people are worried about holding onto cash balances that will lose real value. They view stocks as a safer holding in that environment than cash. (Right or wrong, I am one of those investors!) Is this logically equivalent to “the big problem is demand” and/or “rooting strongly for higher inflation”? I can tell you that many investors are concerned about inflation and they don’t know where to put their money… I’m not sure they are rooting strongly for higher inflation. Perhaps Scott or other economists can tell me how these feelings map to their models.

Really, isn’t that cute? Scott says he can’t even think of an alternative explanation, to his own preferred one. Then a guy in the comments meekly raises his hand and says, “Well, I know that I’m really worried about price inflation, and a lot of people think stocks might be a better hedge. But I’m not as smart as you Scott, so please tell me what your model says about what I’m really doing.”

Of course, the guy wasn’t being sarcastic, even though I can’t paraphrase him without sounding like it.

What kind of answers will these guys be able to come up with if Bernanke and the State drive us into stagflation? I don’t think we’ll see hyperinflation because I think Bernanke won’t continue to accelerate his printing but I doubt he will stop and let a collapse happen either. I think stagflation is in our near future and I would be curious to see if you could guess their response ahead of time?

My guess is that all of a sudden, Scott will realize the Obama Administration’s policies are stalling real output growth.

In addition, I think you would see another revision in the CPI formula.

Yep, they always have the option of redefining the measure. As long as you forget what the purpose of a metric is, you won’t even notice the contradiction between low CPI and your food steadily tasting worse each week, and will continue to post on your top econ blog about all the dumb cranks that were wrong about inflation, and sorry for the late update but my ISP didn’t have power.

> and your food steadily tasting worse each week

Seriously? You’re actually experiencing this in any noticeable statistically significant manner? Are you trying to argue that food taste and quality has been on a decline since inflation started becoming the norm in the 40s and CPI has failed to capture it?

No, I’m just using a constructing a hypothetical example where one forgets the purpose of CPI, and the implications for doing so.

Quality doesn’t necessarily equate to a discernible difference to many consumers’ tastes, but it’s easy to noticeably change them from the manufacturers standpoint.

Or quality may be interpreted as simply less of the product at the same price in nearly the same packaging.

Actually, I have regularly picked up on food quality declines for many different types of foods, there are a trillion ways for food producers to do this, but perhaps the ordinary customer doesn’t notice much. Maybe not consciously, I suspect they do notice but more subconsciously shift purchasing habits, e.g. they’ll just start to ‘feel’ like they prefer Y over X, rather than think ‘quality of X has declined’.

Also, if improved technology, economies of scale and food production methods (say) gradually halve the actual cost of food production between 1950 and 2011 (as they most certainly have, though I don’t know at what rate), but instead of seeing pricing halve, you see prices stay the same, those who publish CPI will be publishing 0%, and you will think prices are staying the same, but in actual fact there has simply been huge inflation that was hidden and offset by roughly parallel improvements in production efficiencies.

Personally I’m not sure the administration is looking much further than the next re-election cycle, and suspect that they’re dumping money in to engineer another false “recovery” in the hopes that it drags out just long enough that it all crashes on somebody else’s watch, after the next elections. I don’t think they care what happens after that as (a) everyone will blame it on whoever is in charge then and (b) whoever is in charge then will abuse the next crisis anyway to attempt to further consolidate power and make sure their cronies all get their stimulus and bailouts. That’s exactly what the last administration did. Of course it can’t go on forever, somebody will be left holding the grenade when it goes off.

I’ve written a short article on this debate over at the Cobden Centre:

http://www.cobdencentre.org/2011/02/money-is-barren-but-occasionally-covers-us-in-dust/

Current:

Nice to know you have a real name!

Not bad.

The problem with looking at the economic data and telling stories (which I do too,) is that some important things aren’t observable–the demand for money, the natural interest rate, and potential income.

All of these play key roles in the monetary equilibrium-monetary disequilibrium-quasimonetarist approach.

Inflation expecations also play a role, and we do have some, somewhat ambiguous, measures of inflation

expectations.

There are differences between Krugman and Sumner. Krugman generally goes from higher expected inflation to lower real interest rates to higher real expenditure and nominal expenditure to higher output, to higher inflation.

Sumner goes from higher quantity of money, more expected nominal expenditure, simultaneous higher inflation and real output, and expectations of this happening creates higher inflation expectations.

Krugman appears to think that higher expected inflation is necessary to get real interest rates down. Sumner doesn’t think that real interest rates are important to the process. They can go up, down, or stay the same.

As for stock prices, they should go up based on expectations of higher nominal profits in the future. This can be due to more real profits from more real salves and production. But it also can be due to higher prices. If, like Sumner, you expect higher nominal expenditure to effect both prices and output, and that both of these things tend to raise expected nominal profit and so stock price fundamentals, then you will generate something like the chart above.

Bob, Only 4 problems with your post:

1. You misread the graph. It doesn’t show that stocks move in proportion to prices, the scale are vastly different. Stocks move much much more that prices, even prices changes cumulated over 10 years.

2. My model does not predict that all of extra NGDP growth will go into RGDP, that’s what Keynesians sometimes claim (the more extreme versions of Keynesians.) I ALWAYS assume an upward sloping SRAS, although I argue it is relatively flate in deep recessions. but never completely flat. Indeed just yesterday I was arguing that point with Andy Harless in an unrelated post; Andy did assume the SRAS was flat.

3. If the stock market liked inflation, as you claim, why did stocks do very poorly during 1966-82? Stocks fell during that period, EVEN IN NOMINAL TERMS, despite a huge increase in the price level. Then when inflation slowed dramatically after 1982, stocks started soaring.

4. You counter-theory doesn’t explain the time-varying pattern. Why did stocks only become correlated with inflation after 2008? That’s the key point that everyone seems to miss.

You misread the graph. It doesn’t show that stocks move in proportion to prices, the scale are vastly different. Stocks move much much more that prices, even prices changes cumulated over 10 years.

I didn’t get that interpretation from Murphy’s post. He didn’t say that a rise and fall of the stock market corresponds to an equally proportional rise and fall in the prices such that they have the same scale. He is just saying that the graph shows stock prices rise when 10 year inflation expectations rises, and fall when 10 year inflation expectations fall (at least since 2008). He referred to expectations of the future price level because that is another way of saying expectations of future inflation. He didn’t say the correspondence was one-to-one in the same scale, as it were, but rather he is just repeating what you already said, which is that there is a very strong comovement between stock prices and inflation expectations, at least since 2008. He is just paraphrasing your existing interpretation of the graph from your blog post.

My model does not predict that all of extra NGDP growth will go into RGDP, that’s what Keynesians sometimes claim (the more extreme versions of Keynesians.) I ALWAYS assume an upward sloping SRAS, although I argue it is relatively flate in deep recessions. but never completely flat. Indeed just yesterday I was arguing that point with Andy Harless in an unrelated post; Andy did assume the SRAS was flat.

Murphy said:

“To restate the important conclusion: Sumner and I both agree that pumping in a trillion new dollars would raise NGDP. But I think it would (mostly) show up as increases in P, without raising RGDP (much). Sumner in contrast thinks it would (mostly) show up as an increase in RGDP, without raising P (much).”

He didn’t claim that your position (or your model) was that ALL the additional NGDP would go into RGDP. He just repeated your position that MOST of the additional NGDP would go into RGDP, or, in other words, the additional NGDP will not simply raise prices, but will raise RGDP, and if done “right”, will raise RGDP by more than any rise in prices, if at all.

I don’t see how you can interpret him to be claiming that your model predicts one to one NGDP to RGDP correspondence.

3. If the stock market liked inflation, as you claim, why did stocks do very poorly during 1966-82? Stocks fell during that period, EVEN IN NOMINAL TERMS, despite a huge increase in the price level. Then when inflation slowed dramatically after 1982, stocks started soaring.

It depends on investor expectations versus actual Fed action. You are looking at it from a much too mechanical manner. Subjective valuations are always the proximate cause for economic data.

Murphy’s position is that inflation EXPECTATIONS are the primary driver of stock prices (and that these expectations are not just ephemeral thoughts, they are themselves a function of the existence of the Fed and their ability to inflate). If the consumer price level is rising rapidly, then investors would probably expect the Fed to tighten up at some point, causing investors to price in lower future inflation, and hence depress stock prices.

By 1982, Volcker was committed to lowering inflation, and he tightened policy up fairly dramatically, raising the Fed funds rate to over 19% by late 1981. This of course send signals throughout the market that in 10 years, the EXPECTATIONS of investors would be that there is nowhere for inflation to go but up, especially over a 10 year time frame.

Because investors expected prices to only go up from 1982 on, they priced that into stocks, and stocks started to rise over time.

This fits Murphy’s story fairly well. It is investor expectations that are the primary driver of stock prices, and the higher their expectations are for future inflation, the higher they will price stocks in the present.

I bet that today, for the short to medium term, if price inflation begins to rise at a much faster pace, then stock prices will begin to fall from their current boom, because the faster prices rise, and given that investors expect the Fed to be able to control inflation, the more they will expect the Fed to tighten up and fight it in the future. That will compel investors to price in expectations of lower future price inflation, and thus they will lower stock prices in the present.

4. You counter-theory doesn’t explain the time-varying pattern. Why did stocks only become correlated with inflation after 2008? That’s the key point that everyone seems to miss.

Well, in the short term, in the initial stages of economic collapse, investors dropped risky stocks and flocked to safer assets like bonds. I think that explains the short term correlation between stocks and inflation expectations. At that point, investors viewed the Fed as a price stabilizer, not a central planner. However, the Fed then intervened more than it has ever done in history. The Fed became, in investor expectations, a major market player. The Fed promised to “not repeat the same mistakes as in the 1930s”. They would print as much money as they wanted to prevent a recession/depression. Investors believed the Fed, and since then investors have priced stocks pretty much solely on account of inflation expectations.

As many market players will tell you, stock market fundamentals are becoming a thing of the past. So many stock investors are paying more and more attention to the Fed, which means paying more attention to inflation/deflation. Quite justifiably. The Fed has made it clear that they will buy up anything that doesn’t move if it means saving banks, preventing unemployment, etc.

If the real economy is expected to go up or down, it matters less now, because investors are planning around the Fed much more than they are planning around real market fundamentals. The Fed has been inflating like crazy, and yet consumer prices have, at least until recently, been rising quite modestly. Investors expect that as long as consumer prices are contained, the Fed will keep printing and printing, and that printing will eventually raise prices in the future. They are therefore pricing that expectation of future inflation into stocks today. This is why stocks are closely matching inflation expectations more than real market fundamentals.

The real economy is still in a state of depression, investors know this, which is why the ratio of insider selling to buying has been mind-bogglingly high for the past year or so. There is no justification for stock prices to rise in recent times except for expectations concerning nominal inflation generated by the Fed. That’s why the correspondence has been so tight since 2008, the last time the economy was appearing to operate OK.

The adherence to “aggregate demand” as the primary conceptual tool is a rather crude, hammer like tool that makes every economic nuance seem like a nail that needs bashing. It doesn’t take into account investor expectations. One would think that a model that seeks to explain stock prices, at least in the short to medium term, would at least contain investor expectations!

Scott, what would the chart have needed to look like, to vindicate people who claim that throwing money at the problem will at best only boost the stock market because of higher inflation expectations?

Bob,

As I understand it, there is no way the chart could have looked that would have undermined your position, so why does there have to be a way the chart would look that would vindicate your position?

Right, which is why I wouldn’t have posted the chart saying, “A ha!”

Scott is the one saying this chart proves he is right. So I want him to tell us what would have proved he was wrong. If the stock market had soared, while inflation expectations remained stable, I would have equally expected him to claim victory.

Gotcha. That makes sense.

>If the stock market had soared, while inflation expectations remained stable, I would have equally expected him to claim victory.

Sumner argues that monetary policy works through inflation or NGDP expectations. If inflation expectations remain stable/low ands stock market soared, I think that would prove him wrong. Not sure how he would claim victory.

The entire concept of “sticky wages” is preposterous. There’s an artificial boom induced by diluted funny money. People are drawn into unsustainable lines of production. The bust/correction starts and people find that their goods and services are now seen as overpriced. No one will hire them or buy their stuff from them at these inflated prices. At some point, they are going to decide it’s better to lower their wages/prices than starve to death. And who cares if they do? By definition, these people are either economic illiterates or economics deniers. Someone just needs to sit them down and explain reality to them.

I fail to see how an alleged army of such obviously obtuse people is justification for another round of money dilution, theft of purchasing power, Cantillon Effects and distortion of the price and capital structure.

I suppose that if they make up 75% of the population and are about to re-open Auschwitz if they don’t get their way, it might be wise to accomodate them. But that’s a political issue, not an economics issue.

The entire concept of “sticky wages” is preposterous.

You need to read Bob Murphy’s article about why sticky wages make perfect sense economically.

At some point, they are going to decide it’s better to lower their wages/prices than starve to death. And who cares if they do? By definition, these people are either economic illiterates or economics deniers.

First of all, I care whether or not people starve to death (even people who are economically illiterate).

Second, the issue with sticky wages isn’t simply that the unemployed aren’t willing to lower their wage demands. It’s that employers won’t hire them even for reduced wages because they don’t want to piss off existing employees. Austrians understand this point when it comes to unionized workers, but even non-unionized can cause employers a lot of problems if morale turns bad.

Which is nothing but a problem of practical politics.

When the neighborhood is run by thugs, we trick them into lowering their wages and prices with money dilution without them realizing what is happening.

We do this so we don’t get beat up, or bombed out.

Bob,

Assuming it is just a problem of practical politics, so what?

To translate into Rothbardian hyperbole, if workers are raising their wages by intimidating employers into not hiring the unemployed, then how it is theft to dilute their purchasing power? It’s not theft to take back something that’s been stolen.

At least we’ve finally stated the issue in a calm, professional and dignified manner. Suppose we have a guy who’s 50 pounds overweight. I say put down that Pop Tart, eat some broccoli and start exercising. You say shoot him up with crystal meth.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DMzoqpyUbhg

And don’t blame Rothbard. I’m perfectly capable of drafting my own hyperbole.

Bob Roddis,

Your example isn’t analogous, in that (among other things) the fat man hasn’t taken something that doesn’t belong to him.

@blackadder

Bob, read the article I linked to above.

OK. Just to clarify, I don’t think that the Fed should suck out money to try to restore prices to their 1913 level.

To be clear I was replying to Bob Roddis there, not you.

I know you’re not advocating deflation back to 1913 levels, I had a line in the article mentioning this I took it out to save space. I should probably have left it in. But, some others on the 100% reserve side are taking the position that deflation is neutral, which is what I was criticising.

I admit that deflation can be horrible. But what do we do about it?

I was thinking, since banks “lend” out “money” that they never earned by creating it out of pixie dust, is there a moral obligation to pay it back in “real” money, especially during post-boom deflationary times?

Also, why doesn’t money dilution cause contracts in fixed dollar amounts to be void for ambiguity? Actually, some hot shot lawyer suggested to me that that would be the case if “this guy you say won the Nobel Prize” [Hayek] is correct.

Personally I don’t think there is anything wrong with what fractional-reserve banks do. I think that the complaint that they’re unethical in some way is mistaken. But, that’s a discussion for another day.

Also, why doesn’t money dilution cause contracts in fixed dollar amounts to be void for ambiguity?

It’s not clear why. If a contract specifies payment in nominal terms, then it is paying that nominal amount that fulfills the contract.

I admit that deflation can be horrible. But what do we do about it?

Well, we could try to prevent it from happening.

I saw Krugman post this first yesterday (of course he declared victory), then saw it on several other econ blogs. What I’ve been thinking about since, is why the series diverge so much between 2006 and 2008. I went back and re-read the Mises Daily How the Stock Market and Economy Really Work, which said that inflation is what fuels stock market gains, so the 2006 to 2008 period really doesn’t make sense. Perhaps it may have something to do with the run up in commodities that happened during the same period. I’m not sure what to think yet.

And yes Bob, you economists are not helping me at all. Despite all of the various theories and explanations, you have all declared yourself to be correct.

A stock market boom is one form of credit expansion. Dollars loaned to business in the form of new stock purchases show up in commercial banks and are subject to being loaned out again, thereby increasing the money supply. Most adults who invest understand how this works, so it is no surprise that expectations of future inflation might track more or less with the stock market ups and downs. This would not be expected to consititue a law however, as other factors can certainly come into play.

Another point: Inflationary credit exapansion can take any number of potential pathways depending on the specific circumstances. Business growth forecasts based on a ready supply of cheap money certainly exert an important influence on the market.

One final point: all things being equal, a boom in the stock market is inconsistent with an excess demand for money, as individuals and institutional investors have loaned out their money instead of attempting to increase their cash holdings. This implies that they already possess a surplus of cash holdings under the circumstances, and at that moment in time when the stock purchase is made, they economize by judging that their rate of return will be greater through the purchase of stocks than in the holding of additional money in CD’s.

Bob

I think its time for you to go back all the way – to David Hume, as even he realized that nominal shocks have REAL effects. That simply has not been disputed by anyone for a while – not even Austrians like Mises or Hayek.

Bob doesn’t deny that monetary shocks do not have real effects.

He just doesn’t agree that this fact alone justifies more monetary shocks, because the Austrian position is that the real effects of inflation are what cause the future monetary shocks that quasi-monetarists can’t account for.

I think its time for you to go back all the way – to David Hume, as even he realized that nominal shocks have REAL effects. That simply has not been disputed by anyone for a while – not even Austrians like Mises or Hayek.

Why would I need to go back to David Hume to get that point? I need only go back to the 4th paragraph of this blog post:

“So far, so good. And to be clear, Austrian economists agree that monetary disturbances can affect the “real” economy; that’s the essence of the Mises-Hayek theory of the business cycle.”

BTW Bob you still have to contend with the miserable failure of your hyperinflation call.

Please take that into account also when evaluating the evidence

As opposed the spectacular success of the Keynesians who predicted lower unemployment that what we have today WITHOUT the stimulus?

I’m not familiar with his call for hyperinflation. I know he was calling for a rise in CPI to around 5% or so (could be off there) in 2009 which isn’t hyperinflation by any means. Also if you started hedging against inflation by investing in gold or silver back then I don’t think you would be cursing Dr. Murphy for his inflation call. If prices keep moving like they’ve been the past couple months then the only thing Dr. Murphy will have to explain is why he was off on the timing. Big Ben isn’t going to let any of us protecting against inflation down. He’ll print until he drives the dollar down significantly.

Can you remind me of my hyperinflation call?

I think this post may be what Contemplationist has in mind:

I have been warning of severe price inflation for some time, and when people ask me “hyperinflation?” I respond, “What do you mean by ‘hyper’?” Recently someone coaxed a number of 25% annual inflation out of me, since I think Bernanke will do what needs to be done to bring it down to the maximum acceptable level, which I somewhat arbitrarily put at about 25%. (Of course the true increase in CPI will probably be more like 35%, but the official press releases–if you have a gun to my head and force me to pick a number–I’m picturing around 25%.)

Personally I would not consider 25-35% annual inflation to be “hyperinflation.” But I can see how someone might use the term in a hyperbolic sense to refer to that situation (which I take it was the point of your “what do you mean by hyper?” question).

If that’s what he has in mind, it’s funny. The entire post is dedicated to arguing that Faber is wrong to predict hyperinflation for the US; that’s even the title of the post.

And nothing I said in that post has been contradicted. I didn’t put a time frame on it there.

I have made at least two (possibly more) specific predictions about CPI that have been very wrong. And I have acknowledged at least two of them publicly on this blog in a dedicated post.

I never predicted hyperinflation.

Meaning, I never said, “Hyperinflation next year.” I still think it is entirely possible that the plan is to crash the dollar and replace it with a regional currency. So it wouldn’t shock me if we had hyperinflation at some point.

And nothing I said in that post has been contradicted. I didn’t put a time frame on it there.

In the comments you clarified that you were talking about 2009/2010 for when the 25% inflation would hit (you said something like “Bernanke might be able to hold us under double digit inflation this year, but by next year he’ll be out of options”).

Unfortunately the comments for your old posts aren’t preserved, but I’m not making this up.

I never predicted hyperinflation.

You’re right. 25-35% inflation is not hyperinfation. I was suggesting that maybe Contemplationist misremembered what you said based on this post.

I don’t remember saying that, but I admit it is possible. It’s a good thing the site upgrade destroyed those comments (ha ha).

I still think it is entirely possible that the plan is to crash the dollar and replace it with a regional currency.

You mean like separate currencies for New England, the Mid West, etc.? Or is this a North American Union thing?

Amero baby.

Captain Freedom, You say I misquoted Murphy. Did or did not Bob make the following claim about my views:

“In contrast, I would have thought Sumner’s position would logically entail that monetary pumping should lead to rising stock prices with stable (price) inflation expectations.”

That is not my claim. My claim is that stock prices would rise much more than inflation expectations, which is exactly what happened. Bob has no plausible theory for why higher inflation expectations didn’t raise stock prices before 2008.

Captain Freedom, You say I misquoted Murphy.

Not really misquoted. More like misread.

Did or did not Bob make the following claim about my views:

“In contrast, I would have thought Sumner’s position would logically entail that monetary pumping should lead to rising stock prices with stable (price) inflation expectations.”

That is not my claim. My claim is that stock prices would rise much more than inflation expectations, which is exactly what happened.

Well, to be fair, he didn’t actually attribute to you as explicitly holding that position. It is only what he thought logically follows from your position.

You argued that inflation would raise the expectations and prospects for future income growth, which would be “soaked up” by an expansion of real output, since real productivity would otherwise have fallen on account of a decline in “aggregate demand”. Inflation would have allegedly reversed that decline in productivity, such that prices for final goods would remain stable, while stock prices would rise on account of increased prospects for growth.

Bob has no plausible theory for why higher inflation expectations didn’t raise stock prices before 2008.

Well, to be completely open and fair, a theory can only be plausible to the quasi-monetarist if it accepted the worldview that a decline in aggregate demand, brought about by a failure of the Fed to inflate enough, in combination with given sticky prices, as ultimately responsible for deep recessions/depressions, which carries with it the inevitable and desired solution for the Fed to create more money.

It’s very difficult to convince quasi-monetarists of alternate views because they refuse to consider the “real” effects generated by inflation during the boom phase, and only seem to focus on the “real” effects of deflation during the bust phase. Austrians hold that it is inflation through credit expansion that negatively affects the real economy during the boom phase, which later on inevitably generates busts and deflation.

If your mental time horizon of considering the economy only goes back to yesterday, then sure, it really looks like deflation is a bad thing and that only inflation can solve the problems. And yes, Austrians do in fact agree with you that rapid deflation generates economic problems. But here is the CRUCIAL difference: Whereas quasi-monetarists just want to treat the symptoms, and stave off deep recession in the short term by increasing inflation, Austrians say doing so will just create more economic distortions that carry with it deflationary potential in the future. This is true even if the economy is in deep recession, and there is lots of supply “slack” and inventory accumulation.

Printing money will not solve the real productive problems that have been infused into the economy due to easy money during the boom. It will only temporarily freeze them in place. Can the quasi-monetarists declare victory for temporarily preventing the economy’s capital distortions made in the run up to the early 2000s bust from being fully manifested in a deep but short depression, only to see another economic bubble replace it, which then bust in 2008?

Just like it would have been better for the economy to sink into a deep but short lived depression in the early 2000s, instead of the Fed inflating another bubble, so too is it better for the Fed to have done nothing after the crash in 2008, instead of blowing up yet another economic bubble.

You say Murphy has no adequate explanation for why inflation expectations did not raise stock prices before 2008. Well, to be fair, Murphy is not the one claiming that the data confirms his story and refutes yours. He is only playing off the empiricist games being played by you cool quasi-monetarist guys and showing you that the data do not necessarily show what you think it shows.

Remember, the Austrian position is that historical economic events can neither confirm nor refute any economic theory. Sound economics is only borne out of a priori logic. If you doubt this, just look at how you and Murphy are interpreting the stock market and inflation expectation data from 2008 to now. It’s the same data, and yet everyone is interpreting the data differently. Why? It’s because each of you are approaching the data using a different a priori theory. Don’t presume to think that your theory is correct because it is more consistent with economic data whereas Murphy’s theory is not. Neither of your theories can be refuted or confirmed by looking at what happened up to 2008, and 2008 to now.

Aggregate demand is a statistic that you think has a primacy force to it all on its own. When asked what causes it to fall, quasi-monetarists do not have an adequate explanation. Consumer stinginess, animal spirits, all these are terrible explanations because there is no good reason for why consumers would wake up one day and stop consuming, nor is there a good reason why investors would become spooked for no good reason. Murphy has the superior theory for why aggregate demand would suddenly fall. Because he has the superior theory, he knows what to do about rapidly declining aggregate demand in our economy.